In animal study, inflammation stops cells from accessing iron needed for brain development.

Researchers exploring the link between newborn infections and later behavior and movement problems have found that inflammation in the brain keeps cells from accessing iron that they need to perform a critical role in brain development.

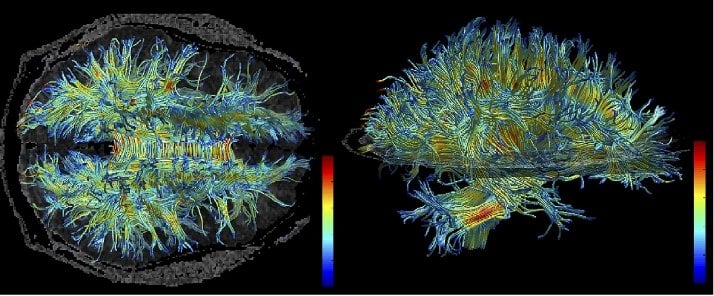

Specific cells in the brain need iron to produce the white matter that ensures efficient communication among cells in the central nervous system. White matter refers to white-colored bundles of myelin, a protective coating on the axons that project from the main body of a brain cell.

The scientists induced a mild E. coli infection in 3-day-old mice. This caused a transient inflammatory response in their brains that was resolved within 72 hours. This brain inflammation, though fleeting, interfered with storage and release of iron, temporarily resulting in reduced iron availability in the brain. When the iron was needed most, it was unavailable, researchers say.

“What’s important is that the timing of the inflammation during brain development switches the brain’s gears from development to trying to deal with inflammation,” said Jonathan Godbout, associate professor of neuroscience at The Ohio State University and senior author of the study. “The consequence of that is this abnormal iron storage by neurons that limits access of iron to the rest of the brain.”

The research is published in the Oct. 9, 2013, issue of The Journal of Neuroscience.

The cells that need iron during this critical period of development are called oligodendrocytes, which produce myelin and wrap it around axons. In the current study, neonatal infection caused neurons to increase their storage of iron, which deprived iron from oligodendrocytes.

In other mice, the scientists confirmed that neonatal E. coli infection was associated with motor coordination problems and hyperactivity two months later – the equivalent to young adulthood in humans. The brains of these same mice contained lower levels of myelin and fewer oligodendrocytes, suggesting that brief reductions in brain-iron availability during early development have long-lasting effects on brain myelination.

The timing of infection in newborn mice generally coincides with the late stages of the third trimester of pregnancy in humans. The myelination process begins during fetal development and continues after birth.

Though other researchers have observed links between newborn infections and effects on myelin and behavior, scientists had not figured out why those associations exist. Godbout’s group focuses on understanding how immune system activation can trigger unexpected interactions between the central nervous system and other parts of the body.

“We’re not the first to show early inflammatory events can change the brain and behavior, but we’re the first to propose a detailed mechanism connecting neonatal inflammation to physiological changes in the central nervous system,” said Daniel McKim, a lead author on the paper and a student in Ohio State’s Neuroscience Graduate Studies Program.

The neonatal infection caused several changes in brain physiology. For example, infected mice had increased inflammatory markers, altered neuronal iron storage, and reduced oligodendrocytes and myelin in their brains. Importantly, the impairments in brain myelination corresponded with behavioral and motor impairments two months after infection.

Though it’s unknown if these movement problems would last a lifetime, McKim noted that “since these impairments lasted into what would be young adulthood in humans, it seems likely to be relatively permanent.”

The reduced myelination linked to movement and behavior issues in this study has also been associated with schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders in previous work by other scientists, said Godbout, also an investigator in Ohio State’s Institute for Behavioral Medicine Research (IBMR).

“More research in this area could confirm that human behavioral complications can arise from inflammation changing the myelin pattern. Schizophrenia and autism disorders are part of that,” he said.

This current study did not identify potential interventions to prevent these effects of early-life infection. Godbout and colleagues theorize that maternal nutrition – a diet high in antioxidants, for example – might help lower the inflammation in the brain that follows a neonatal infection.

“The prenatal and neonatal period is such an active time of development,” Godbout said. “That’s really the key – these inflammatory challenges during critical points in development seem to have profound effects. We might just want to think more about that clinically.”

Notes about this neurodevelopment and behavioral neuroscience research

This work is the result of close collaboration between Godbout; Ning Quan and Michael Bailey of Ohio State’s Division of Oral Biology and the IBMR; Dana McTigue of Ohio State’s Department of Neuroscience and Center for Brain and Spinal Cord Repair; and Staci Bilbo of Duke University. Additional co-authors from Ohio State are Jacqueline Lieblein-Boff (now with Abbott Nutrition), Daniel McKim, Daniel Shea, Ping Wei, Zhen Deng and Caroline Sawicki.

The research was supported by Abbott Nutrition and the National Institutes of Health.

Written by Emily Caldwell

Contact: Emily Caldwell – Ohio State University

Source: Ohio State University press release

Image Source: The image is credited to Kubicki M., McCarley R.W., Westin C-F., Park H-J., Maier S.E., Kikinis R., Jolesz F.A., and Shenton M.E. The image is licensed as Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Original Research: The research will be published in Journal of Neuroscience. We will link to the research when available.