Summary: A new study sheds light on the role oligodendrocytes play in the development and progression of multiple sclerosis.

Source: Karolinska Institute.

Mapping of a certain group of cells, known as oligodendrocytes, in the central nervous system of a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (MS), shows that they might have a significant role in the development of the disease. The discovery can lead to new therapies targeted at other areas than just the immune system. The results are published in Nature Medicine by researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden.

2.5 million people around the world live with MS, with approximately 18,000 people in Sweden, and about 1,000 new cases annually. MS develops when the immune system’s white blood cells attack the insulating fatty substance known as myelin that coats nerve fibres in the central nervous system. This interferes with the proper transmission of nerve electric signals and causes the symptoms of the disease. While it is unknown why the immune system attacks the myelin, a study by researchers at Karolinska Institutet shows that the cells that produce myelin, oligodendrocytes, might play an unexpected role. Oligodendrocytes are one of the most common types of cell in the brain and spinal cord.

“Our study provides a new perspective on how multiple sclerosis might emerge and evolve” says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco, associate professor at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institutet. “Current treatments mainly focus on inhibiting the immune system. But we can now show that the target cells of the immune system in the brain and spinal cord, oligodendrocytes, acquire new properties during disease and might have a higher impact on the disease than previously thought.”

The researchers have shown that a subset of oligodendrocytes and their progenitor cells have much in common with the immune cells, in a mouse model of MS. Among other properties, they can take part in the clearing away of the myelin that is damaged by the disease, in a way that resembles how immune cells operate. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells can also communicate with the immune cells and make them change their behaviour.

“We also see that some genes that have been identified as those that cause a susceptibility to MS are active (expressed) in oligodendrocytes and their progenitors,” says Ana Mendanha Falcão, joint first author of the study with David van Bruggen, both at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics at Karolinska Institutet.

“All in all, this suggests that these cells have a significant role to play either in the onset of the disease or in the disease process,” says David van Bruggen.

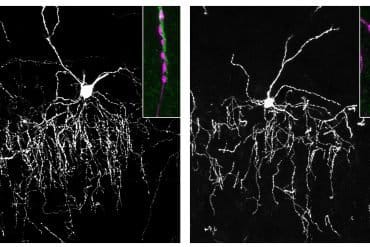

The study was conducted using the recently developed technique, single-cell RNA sequencing, which provides scientists with a snapshot of the genetic activity of single cells and therefore with a much more effective means of differentiating the properties of individual cells. This has made it possible for researchers to identify the various roles and functions of the different cells.

Although the study was largely conducted on mice, some of the results have also been observed in human samples.

“We will now continue with further studies to ascertain the part played by the oligodendrocytes and their progenitor cells in MS,” says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco. “Further knowledge can eventually lead the way to the development of new treatments for the disease.”

Funding: The research was financed by several funding bodies, including the European Union (European Research Council and Marie-Sk?odowska Curie Actions), the European Committee for Treatment and Research of Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS), the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Brain Foundation, the Ming Wai Lau Centre for Reparative Medicine, the Petrus and Augusta Hedlund Foundation and Karolinska Institutet..

Source: Karolinska Institute

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Abstract for “Disease-specific oligodendrocyte lineage cells arise in multiple sclerosis” by Ana Mendanha Falcão, David van Bruggen, Sueli Marques, Mandy Meijer, Sarah Jäkel, Eneritz Agirre, Samudyata, Elisa M. Floriddia, Darya P. Vanichkina, Charles ffrench-Constant, Anna Williams, André Ortlieb Guerreiro-Cacais & Gonçalo Castelo-Branco in Nature Medicine. Published November 12 2018.

doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0236-y

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Karolinska Institute”New Clues to Origin and Progression of Multiple Sclerosis.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 12 November 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/ms-origin-progression-10187/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Karolinska Institute(2018, November 12). New Clues to Origin and Progression of Multiple Sclerosis. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved November 12, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/ms-origin-progression-10187/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Karolinska Institute”New Clues to Origin and Progression of Multiple Sclerosis.” https://neurosciencenews.com/ms-origin-progression-10187/ (accessed November 12, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Disease-specific oligodendrocyte lineage cells arise in multiple sclerosiss

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is characterized by an immune system attack targeting myelin, which is produced by oligodendrocytes (OLs). We performed single-cell transcriptomic analysis of OL lineage cells from the spinal cord of mice induced with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), which mimics several aspects of MS. We found unique OLs and OL precursor cells (OPCs) in EAE and uncovered several genes specifically alternatively spliced in these cells. Surprisingly, EAE-specific OL lineage populations expressed genes involved in antigen processing and presentation via major histocompatibility complex class I and II (MHC-I and -II), and in immunoprotection, suggesting alternative functions of these cells in a disease context. Importantly, we found that disease-specific oligodendroglia are also present in human MS brains and that a substantial number of genes known to be susceptibility genes for MS, so far mainly associated with immune cells, are expressed in the OL lineage cells. Finally, we demonstrate that OPCs can phagocytose and that MHC-II-expressing OPCs can activate memory and effector CD4-positive T cells. Our results suggest that OLs and OPCs are not passive targets but instead active immunomodulators in MS. The disease-specific OL lineage cells, for which we identify several biomarkers, may represent novel direct targets for immunomodulatory therapeutic approaches in MS.