Summary: According to researchers, some synapses get smaller as we learn new information.

Source: Salk Institute.

Those of us who can’t resist tourist tchotchkes are big fans of suitcases with an expandable compartment. Now, it turns out the brain’s capacity for storing new memories is expandable, too, with limitations.

Salk Institute scientists and collaborators at the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Otago, in New Zealand, found that connections in the brain not only expand as needed in response to learning or experiencing new things, but that others will shrink as a result. The work, which could shed light on conditions in which memory formation is impaired, such as depression or Alzheimer’s disease, appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on February 20, 2018.

“The brain has the capacity to store an immense amount of information at the synapses between nerve cells,” says Professor Terrence Sejnowski, who is head of the Salk’s Computational Neurobiology Laboratory and co-corresponding author of the new paper. “So although we already knew where memories are stored, this work helps clarify how they are stored.”

Every time you look at something new, or have a new thought, millions of brain cells communicate that information to each other in the form of electrical and chemical signals across tiny gaps called synapses. It was known that synapses can grow larger–that is, become more likely to release chemicals (or release more of them) to better transmit information to receiving neurons. However, little is known about normal function and disruptions in synaptic communication, the latter of which is a hallmark of many neuropsychiatric conditions and memory impairment.

Previously, Sejnowski used 3D computer reconstructions and modeling to uncover that the brain’s memory capacity is 10 times greater than had been thought. In the new work, he and collaborators in Texas and New Zealand decided to further investigate brain function by stimulating a region in rodents’ brains important for memory, called the hippocampus. This allowed the researchers to mimic, under very controlled conditions, the effect that a new experience would have on a brain region common to mammals.

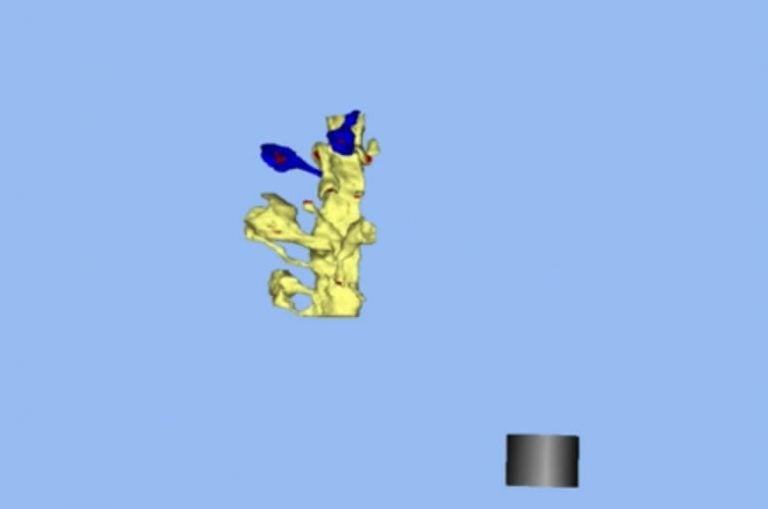

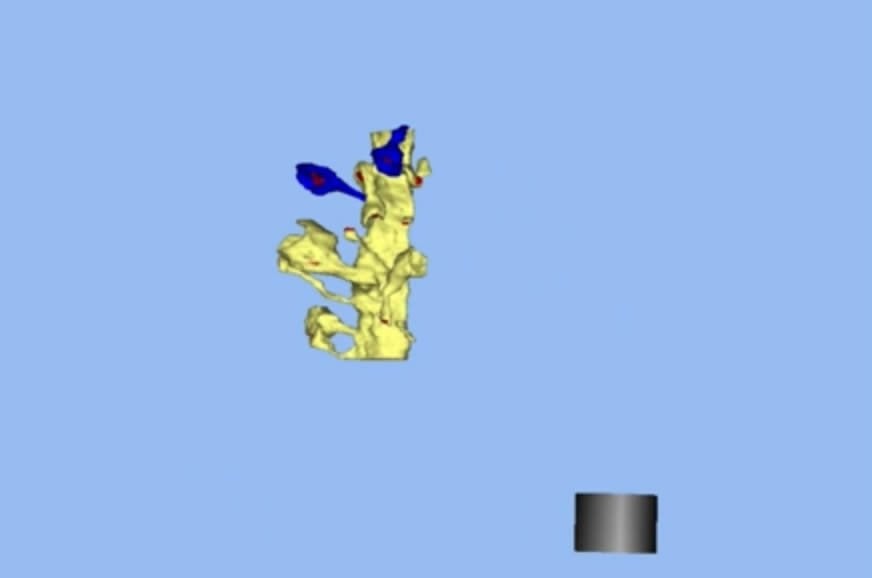

The researchers imaged the hippocampal brain samples using electron microscopy and analyzed the resulting data. They expected to see synapses get bigger, which they are known to do in a process of learning known as long-term potentiation. What they did not expect–but found–was that, as some synapses got bigger, others got smaller.

“It’s an intuitive idea that as we learn something new, synapses strengthen and get bigger,” says Sejnowski. “This shows that there is a balance: some get stronger, some get weaker.”

Sejnowski says that the results make sense because if synapses only got bigger, they’d reach a limit and no new information could be stored, but this is the first time the connection has been demonstrated. The work also reveals that by increasing the range of synaptic sizes, the overall storage capacity goes up–you can have more synapses, large and small.

Interestingly, when the team quantitatively estimated how much synaptic information could be stored in two different areas of the hippocampus–the dentate gyrus and CA1–the amounts varied dramatically, which may be related to differences in their functions.

“We hope to explore many additional questions such as whether the increase in information storage is accompanied by a compensatory decrease in information storage capacity in adjoining layers, and how long the temporary increase in storage capacity at particular synapses lasts,” says Cailey Bromer, a Salk research associate and first author of the study.

Funding: The work was funded by NIH Grants NS21184, MH095980 and MH104319; National Science Foundation NeuroNex Grant 1707356; Grants GM103712 and MH079076; a University of Otago postgraduate scholarship; the Texas Emerging Technologies Fund; and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Source: Rhiannon Bugno – Salk Institute

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to UT Austin/Salk Institute.

Original Research: Abstract in PNAS.

doi:10.1073/pnas.1716189115

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Salk Institute “Making New Memories is a Balancing Act.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 14 March 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/synapses-memory-8633/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Salk Institute (2018, March 14). Making New Memories is a Balancing Act. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved March 14, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/synapses-memory-8633/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Salk Institute “Making New Memories is a Balancing Act.” https://neurosciencenews.com/synapses-memory-8633/ (accessed March 14, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Long-term potentiation expands information content of hippocampal dentate gyrus synapses

An approach combining signal detection theory and precise 3D reconstructions from serial section electron microscopy (3DEM) was used to investigate synaptic plasticity and information storage capacity at medial perforant path synapses in adult hippocampal dentate gyrus in vivo. Induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) markedly increased the frequencies of both small and large spines measured 30 minutes later. This bidirectional expansion resulted in heterosynaptic counterbalancing of total synaptic area per unit length of granule cell dendrite. Control hemispheres exhibited 6.5 distinct spine sizes for 2.7 bits of storage capacity while LTP resulted in 12.9 distinct spine sizes (3.7 bits). In contrast, control hippocampal CA1 synapses exhibited 4.7 bits with much greater synaptic precision than either control or potentiated dentate gyrus synapses. Thus, synaptic plasticity altered total capacity, yet hippocampal subregions differed dramatically in their synaptic information storage capacity, reflecting their diverse functions and activation histories.