Summary: A new study has identified racial disparities between African Americans and Caucasians in the level of a key biomarker used to identify Alzheimer’s disease.

Source: WUSTL.

African-Americans may be twice as likely as Caucasian Americans to develop Alzheimer’s disease, but nobody knows why because studies investigating the underlying causes of illness have historically drawn from a nearly all-white pool of research participants. Consequently, little is known about how the neurodegenerative disease arises and progresses in people of non-Caucasian backgrounds.

Now, a new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has identified racial disparities between African-Americans and Caucasians in the level of a key biomarker used to identify Alzheimer’s disease. The findings, published Jan. 7 in JAMA Neurology, suggest that tools to diagnose the illness may not as effectively apply to African-Americans. Specifically, the concern is that Alzheimer’s may be under-recognized in African-Americans because they typically have lower levels of the brain protein tau – meaning that people might not meet the threshold to be diagnosed when the disease already has begun to develop in their brains.

“If we only study Alzheimer’s in Caucasians, we’ll only learn about Alzheimer’s in Caucasians,” said John C. Morris, MD, the Harvey A. and Dorismae Hacker Friedman Distinguished Professor of Neurology. “If we want to understand all the ways the disease can develop in people, we need to include people from all groups. Without a complete understanding of the illness, we’re not going to be able to develop therapies that work for all people.”

Morris leads the university’s Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). When he took over as principal investigator in 1997, Morris launched an initiative to address the lack of knowledge about the disease in people of color, and started by diversifying the center’s pool of study participants. At the time, only about 5 percent of people enrolled in memory and cognitive studies at the center were African-American, though they made up 18 percent of the population in the greater St. Louis area. With the guidance of an African-American advisory board led by civil rights activist Norman R. Seay, the ADRC steadily attracted a more representative participant group that allowed researchers to investigate the roots of racial differences in Alzheimer’s.

For this study, Morris and colleagues analyzed biological data from 1,215 people, of whom 14 percent, or 173, were African-American. The participants averaged 71 years of age. Two-thirds showed no signs of memory loss or confusion, and the remaining one-third had either very mild or mild Alzheimer’s dementia. All participants underwent at least one test for Alzheimer’s: a PET scan to detect plaques of toxic amyloid protein in the brain, an MRI scan for signs of brain shrinkage and damage, or a spinal tap to measure levels of key Alzheimer’s proteins in the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

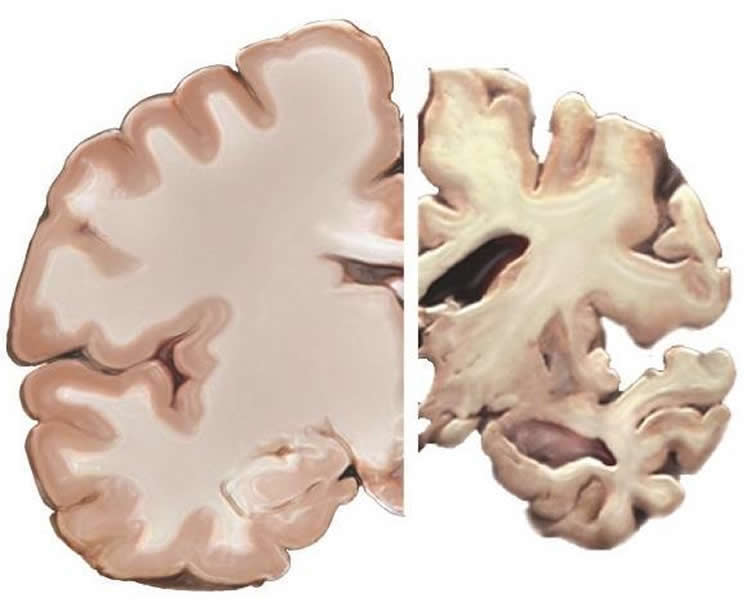

Analysis of the MRI and PET scans turned up no significant differences between African-Americans and whites. But when the researchers examined the samples of cerebrospinal fluid, they discovered that African-Americans had significantly lower levels of the brain protein tau. Elevated tau has been linked to brain damage, memory loss and confusion, but having lower levels of tau didn’t protect African-Americans from those problems. They were just as likely as Caucasians to be cognitively impaired in this study.

“With tau, the pattern was the same in African-Americans and whites – the higher your tau level, the more likely you were cognitively impaired – but the absolute amounts were consistently lower in African-Americans,” Morris said. “What this may indicate is that the cutoffs between normal and high levels of tau that were developed by studying whites are probably not accurate for African-Americans and could cause us to miss signs of disease in some people.”

This difference was most pronounced in people with the high-risk form of the gene APOE, known as APOE4. Older Caucasians who carry the APOE4 gene variant have a threefold increase in their risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, making it the single strongest genetic risk factor in that group. But previous studies have found that the gene variant has a much weaker effect in African-Americans.

When Morris and colleagues broke down their data by APOE status, they found that African-Americans with the high-risk form of the gene had lower levels of tau than Caucasians who also carried the risky variant. But among people who carried the low-risk forms of the gene, tau levels were similar, regardless of race.

“It looks like the APOE4 risk factor doesn’t operate the same in African-Americans as it does in whites,” Morris said. “We need to start looking into the possibility that the disease develops in distinct ways in various populations. People may be getting the same illness - Alzheimer’s disease – via different biological pathways.”

A more complete understanding of the ways Alzheimer’s can arise could open up new avenues of research to prevent or treat the devastating disease, the researchers said.

“We’ve been focusing on African-Americans because we have a large African-American community here in St. Louis, but we also need Asian-Americans, Native Americans, Hispanics, everybody to participate in research,” Morris said. “I think we’ll find we’ve been missing a lot by having such limited study populations in the past. We need to find out what else is going on, so we can develop better therapies that apply to everyone.”

Funding: NIH/National Institute on Aging, Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences funded this study.

Source: Diane Duke Williams – WUSTL

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Abstract for “Assessment of Racial Disparities in Biomarkers for Alzheimer Disease” by John C. Morris, MD; Suzanne E. Schindler, MD, PhD; Lena M. McCue, PhD; Krista L. Moulder, PhD; Tammie L. S. Benzinger, MD, PhD4; Carlos Cruchaga, PhD; Anne M. Fagan, PhD; Elizabeth Grant, PhD; Brian A. Gordon, PhD; David M. Holtzman, MD; and Chengjie Xiong, PhD in JAMA Neurology. Published January 7 2019.

doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4249

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]WUSTL”Racial Differences in Alzheimer’s Unveiled.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 7 January 2019.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/alzheimers-differences-10442/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]WUSTL(2019, January 7). Racial Differences in Alzheimer’s Unveiled. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved January 7, 2019 from https://neurosciencenews.com/alzheimers-differences-10442/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]WUSTL”Racial Differences in Alzheimer’s Unveiled.” https://neurosciencenews.com/alzheimers-differences-10442/ (accessed January 7, 2019).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Assessment of Racial Disparities in Biomarkers for Alzheimer Disease

Importance

Racial differences in molecular biomarkers for Alzheimer disease may suggest race-dependent biological mechanisms.

Objective

To ascertain whether there are racial disparities in molecular biomarkers for Alzheimer disease.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A total of 1255 participants (173 African Americans) were enrolled from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2015, in longitudinal studies at the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center at Washington University and completed a magnetic resonance imaging study of the brain and/or positron emission tomography of the brain with Pittsburgh compound B (radioligand for aggregated amyloid-β) and/or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) assays for the concentrations of amyloid-β42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau181. Independent cross-sectional analyses were conducted from April 22, 2016, to August 27, 2018, for each biomarker modality with an analysis of variance or analysis of covariance including age, sex, educational level, race, apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele status, and clinical status (normal cognition or dementia). All biomarker assessments were conducted without knowledge of the clinical status of the participants.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were hippocampal volumes adjusted for differences in intracranial volumes, global cerebral amyloid burden as transformed into standardized uptake value ratios (partial volume corrected), and CSF concentrations of amyloid-β42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau181.

Results

Of the 1255 participants (707 women and 548 men; mean [SD] age, 70.8 [9.9] years), 116 of 173 African American participants (67.1%) and 724 of 1082 non-Hispanic white participants (66.9%) had normal cognition. There were no racial differences in the frequency of cerebral ischemic lesions noted on results of brain magnetic resonance imaging, mean cortical standardized uptake value ratios for Pittsburgh compound B, or for amyloid-β42 concentrations in CSF. However, in individuals with a reported family history of dementia, mean (SE) total hippocampal volumes were lower for African American participants than for white participants (6418.26 [138.97] vs 6990.50 [44.10] mm3). Mean (SE) CSF concentrations of total tau were lower in African American participants than in white participants (293.65 [34.61] vs 443.28 [18.20] pg/mL; P < .001), as were mean (SE) concentrations of phosphorylated tau181 (53.18 [4.91] vs 70.73 [2.46] pg/mL; P < .001). There was a significant race by APOE ε4 interaction for both CSF total tau and phosphorylated tau181 such that only APOE ε4–positive participants showed the racial differences.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this study suggest that analyses of molecular biomarkers of Alzheimer disease should adjust for race. The lower CSF concentrations of total tau and phosphorylated tau181 in African American individuals appear to reflect a significant race by APOE ε4 interaction, suggesting a differential effect of this Alzheimer risk variant in African American individuals compared with white individuals.

[divider]Feel free to share this Neuroscience News.[/divider]