Summary: Researchers report a drug used to slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease may help to reverse memory and learning problems in teens who binge drink.

Source: Duke University.

A drug used to slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease could offer clues on how drugs might one day be able to reverse brain changes that affect learning and memory in teens and young adults who binge drink.

In a study led by Duke Health and published in the journal Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, scientists demonstrate in rats that a short duration of the drug donepezil can reverse both structural and genetic damage that bouts of alcohol use causes in neurons, or nerve cells, in the young brain.

There is limited research on the extent to which alcohol effects the developing brain in teens and adolescents, but it’s evident that drinking during adolescence causes changes in the brain. Much of the research has looked specifically at the hippocampus, which is linked to learning and memory. Whether those changes are permanent is unknown.

“Clinical studies are starting to show that adolescents who drink early and consistently across the college years have some deficits in learning and memory,” said senior author Scott Swartzwelder, Ph.D., professor in psychiatry at Duke. “It’s not a sledgehammer — it’s not knocking their memory out completely — but there are demonstrable, if subtle, effects on their cognitive function.”

Because they can’t ethically subject youth to alcohol to study its effects, researchers use the developing brains of rats to understand the effects of “intermittent alcohol exposure” — the equivalent of drinking to a blood-alcohol level of .08 (the legal limit for driving while impaired) three or four nights a week.

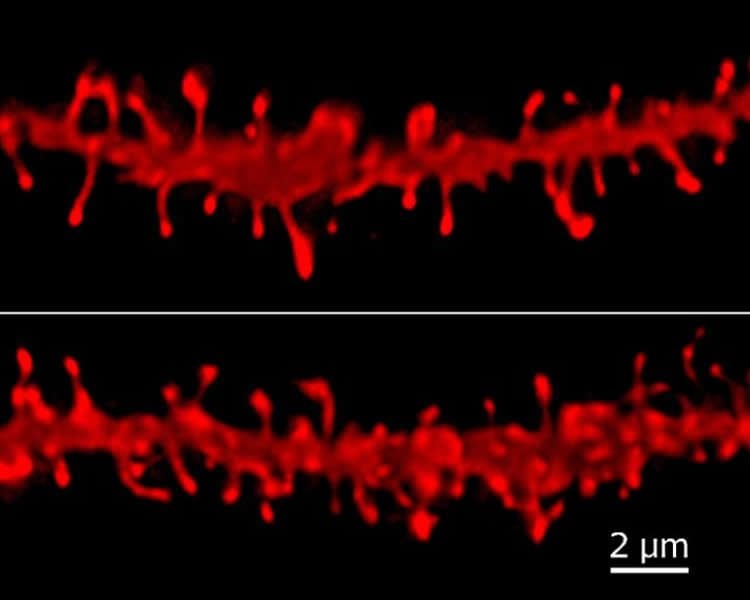

When researchers examined neurons in the brains of adult rats that had been exposed to alcohol when they were adolescents, they found far fewer dendritic spines, which resemble leggy mushrooms stemming from neurons to receive information. What looked like a dense forest of dendritic spines in healthy rats had been reduced to sparse, stubby structures in those previously exposed to alcohol.

“Any change in the density of spines on dendrites tells you those cells are processing information differently than they should be, and whether that processing goes up or down can be a problem,” Swartzwelder said. “They need to be just right. Downstream, these changes can throw a monkey wrench into how cells function. You can imagine how quickly that could multiply in a region of the brain where you’ve got millions of cells interacting.”

But a short course of treatment with donepezil appeared to reverse these changes, restoring the density of dendritic spines.

Through their experiments, the scientists linked changes in the density of dendritic spines to the activity of a gene called Fmr1.

Mutations of the Fmr1 gene are linked to developmental delays and conditions including autism and Parkinson’s disease. Alcohol exposure in rats appeared to change how the Fmr1 gene is regulated, which may have affected the density of dendritic spines. Treatment with donepezil appeared to reverse those changes at the genetic level as well, Swartzwelder said.

As scientists continue to define the effects of alcohol on the developing brain, these findings identify a specific brain function that is diminished through alcohol exposure and a genetic target that could be the key in repairing any damage, he said.

“Studies in humans of the long-term effects of drinking during adolescence are just beginning to emerge, but the data we do have indicate negative cognitive effects, and this puts us one step closer to one day being able to reverse those,” Swartzwelder said.

In addition to Swartzwelder, Duke study authors include Kelsey M. Miller and Hannah G. Sexton, with Patrick J. Mulholland of the Charleston Alcohol Research Center, and Tara L. Teppen and Subhash C. Pandey of the Alcohol Research Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Funding: The research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Source: Sarah Avery – Duke University

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Patrick Mulholland/ Charleston Alcohol Research Center.

Original Research: Abstract in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research.

doi:10.1111/acer.13599

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Duke University “Alzheimer’s Drug Repairs Brain Damage After Alcohol Binges: Rat Study.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 15 February 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/alcohol-brain-damage-alzheimers-drug-8495/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Duke University (2018, February 15). Alzheimer’s Drug Repairs Brain Damage After Alcohol Binges: Rat Study. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved February 15, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/alcohol-brain-damage-alzheimers-drug-8495/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Duke University “Alzheimer’s Drug Repairs Brain Damage After Alcohol Binges: Rat Study.” https://neurosciencenews.com/alcohol-brain-damage-alzheimers-drug-8495/ (accessed February 15, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Donepezil Reverses Dendritic Spine Morphology Adaptations and Fmr1 Epigenetic Modifications in Hippocampus of Adult Rats After Adolescent Alcohol Exposure

Background

Adolescent intermittent ethanol (AIE) exposure produces persistent impairments in cholinergic and epigenetic signaling and alters markers of synapses in the hippocampal formation, effects that are thought to drive hippocampal dysfunction in adult rodents. Donepezil (Aricept), a cholinesterase inhibitor, is used clinically to ameliorate memory-related cognitive deficits. Given that donepezil also prevents morphological impairment in preclinical models of neuropsychiatric disorders, we investigated the ability of donepezil to reverse morphological and epigenetic adaptations in the hippocampus of adult rats exposed to AIE. Because of the known relationship between dendritic spine density and morphology with the fragile X mental retardation 1 (Fmr1) gene, we also assessed Fmr1 expression and its epigenetic regulation in hippocampus after AIE and donepezil pretreatment.

Methods

Adolescent rats were administered intermittent ethanol for 16 days starting on postnatal day 30. Rats were treated with donepezil (2.5 mg/kg) once a day for 4 days starting 20 days after the completion of AIE exposure. Brains were dissected out after the fourth donepezil dose, and spine analysis was completed in dentate gyrus granule neurons. A separate cohort of rats, treated identically, was used for molecular studies.

Results

AIE exposure significantly reduced dendritic spine density and altered morphological characteristics of subclasses of dendritic spines. AIE exposure also increased mRNA levels and H3-K27 acetylation occupancy of the Fmr1 gene in hippocampus. Treatment of AIE-exposed adult rats with donepezil reversed both the dendritic spine adaptations and epigenetic modifications and expression of Fmr1.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that AIE produces long-lasting decreases in dendritic spine density and changes in Fmr1 gene expression in the hippocampal formation, suggesting morphological and epigenetic mechanisms underlying previously reported behavioral deficits after AIE. The reversal of these effects by subchronic, post-AIE donepezil treatment indicates that these AIE effects can be reversed by up-regulating cholinergic function.