Summary: A new study reports those who suffer from persistent depression lasting more than ten years have higher levels of neuroinflammation.

Source: CAMH.

New brain imaging research from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) shows that the brain alters after years of persistent depression, suggesting the need to change how we think about depression as it progresses.

The study, led by senior author Dr. Jeff Meyer of CAMH’s Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, was published today in The Lancet Psychiatry.

The research showed that people with longer periods of untreated depression, lasting more than a decade, had significantly more brain inflammation compared to those who had less than 10 years of untreated depression. In an earlier study, Dr. Meyer’s team discovered the first definitive evidence of inflammation in the brain in clinical depression.

This study provides the first biological evidence for large brain changes in long-lasting depression, suggesting that it is a different stage of illness that needs different therapeutics – the same perspective taken for early and later stages of Alzheimer’s disease, he says.

“Greater inflammation in the brain is a common response with degenerative brain diseases as they progress, such as with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson´s disease,” says Dr. Meyer, who also holds a Canada Research Chair in the Neurochemistry of Major Depression. While depression is not considered a degenerative brain disease, the change in inflammation shows that, for those in whom depression persists, it may be progressive and not a static condition.

Yet currently, says Dr. Meyer, regardless of how long a person has been ill, major depressive disorder is mainly treated with the same approach. Some people may have a couple of episodes of depression over a few years. Others may have persistent episodes over a decade with worsening symptoms, and increasing difficulty going to work or carrying out routine activities.

Treatment options for this later stage of illness, such as medications targeting inflammation, are being investigated by Dr. Meyer and others. This includes repurposing current medications designed for inflammation in other illnesses to be used in major depressive disorder.

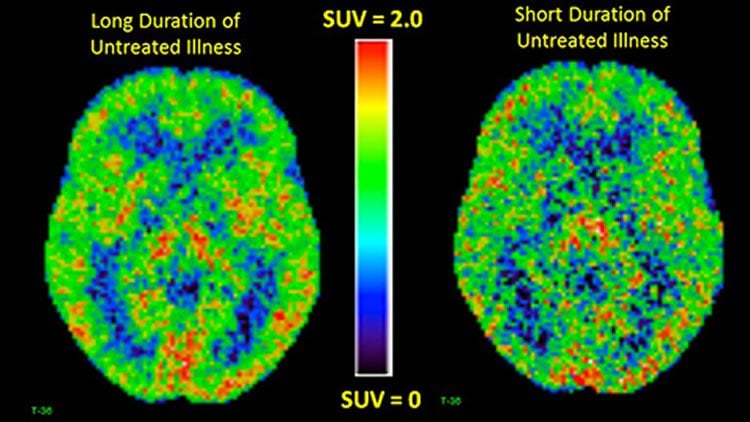

In the study, brain inflammation was measured using a type of brain imaging called positron emission tomography (PET). The brain’s immune cells, known as microglia, are involved in the brain’s normal inflammatory response to trauma or injury, but too much inflammation is associated with other degenerative illnesses as well as depression. When microglia are activated, they make more translocator protein (TSPO), a marker of inflammation that can be seen using PET imaging.

The study involved 25 people with more than 10 years of depression, 25 with less than 10 years of illness, and 30 people with no depression as a comparison group. TSPO levels were about 30 per cent higher in different brain regions among those with long-lasting untreated depression, compared to those with shorter periods of untreated depression. The group with long-term depression also had higher TSPO levels than those with no depression.

Dr. Meyer also notes that in treatment studies, patients with serious, longstanding depression tend to be excluded, so there is a lack of evidence of how to treat this stage of illness, which needs to be addressed.

The joint first authors of the study were post-doctoral fellow Dr. Elaine Setiawan and graduate student Sophia Attwells.

Funding: This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Brain and Behavior Foundation and the Neuroscience Catalyst Fund.

Source: Sean O’Malley – CAMH

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is adapted from the CAMH news release.

Original Research: Abstract in Lancet Psychiatry.

doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30048-8

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]CAMH “Over Years, Depression Changes the Brain.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 28 February 2018.

< https://neurosciencenews.com/depression-brain-changes-8581/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]CAMH (2018, February 28). Over Years, Depression Changes the Brain. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved February 28, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/depression-brain-changes-8581/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]CAMH “Over Years, Depression Changes the Brain.” https://neurosciencenews.com/depression-brain-changes-8581/ (accessed February 28, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Association of translocator protein total distribution volume with duration of untreated major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study

Background

People with major depressive disorder frequently exhibit increasing persistence of major depressive episodes. However, evidence for neuroprogression (ie, increasing brain pathology with longer duration of illness) is scarce. Microglial activation, which is an important component of neuroinflammation, is implicated in neuroprogression. We examined the relationship of translocator protein (TSPO) total distribution volume (VT), a marker of microglial activation, with duration of untreated major depressive disorder, and with total illness duration and antidepressant exposure.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we recruited participants aged 18–75 years from the Toronto area and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Toronto, ON, Canada). Participants either had major depressive episodes secondary to major depressive disorder or were healthy, as confirmed with a structured clinical interview and consultation with a study psychiatrist. To be enrolled, participants with major depressive episodes had to score a minimum of 17 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and had to be medication free or taking a stable dose of medication for at least 4 weeks before PET scanning. Eligible participants were non-smokers; had no history of or concurrent alcohol or substance dependence, neurological illness, autoimmune disorder, or severe medical problems; and were free from acute medical illnesses for the previous 2 weeks before PET scanning. Participants were excluded if they had used brain stimulation treatments within the 6 months before scanning, had used anti-inflammatory drugs lasting at least 1 week within the past month, were taking hormone replacement therapy, had psychotic symptoms, had bipolar disorder (type I or II) or borderline antisocial personality disorder, or were pregnant or breastfeeding. We scanned three primary grey-matter regions of interest (prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and insula) and 12 additional regions and subregions using 18F-FEPPA PET to measure TSPO VT. We investigated the duration of untreated major depressive disorder, and the combination of total duration of disease and duration of antidepressant treatment, as predictor variables of TSPO VT, assessing their significance.

Findings

Between Sept 1, 2009, and July 6, 2017, we screened 134 participants for eligibility, of whom 81 were included in the study (current major depressive episode n=51, healthy n=30). We excluded one participant with a major depressive episode from the analysis because of unreliable information about previous medication use. Duration of untreated major depressive disorder was a strong predictor of TSPO VT (p<0·0001), as were total illness duration (p=0·0021) and duration of antidepressant exposure (p=0·037). The combination of these predictors accounted for about 50% of variance in TSPO VT in the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and insula. In participants who had untreated major depressive disorder for 10 years or longer, TSPO VT was 29–33% greater in the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and insula than in participants who were untreated for 9 years or less. TSPO VT was also 31–39% greater in the three primary grey-matter regions of participants with long duration of untreated major depressive disorder compared with healthy participants (p=0·00047).

Interpretation

Microglial activation, as shown by TSPO VT, is greater in patients with chronologically advanced major depressive disorder with long periods of no antidepressant treatment than in patients with major depressive disorder with short periods of no antidepressant treatment, which is strongly suggestive of a different illness phase. Consistent with this, the yearly increase in microglial activation is no longer evident when antidepressant treatment is given.

Funding

Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Neuroscience Catalyst Fund.