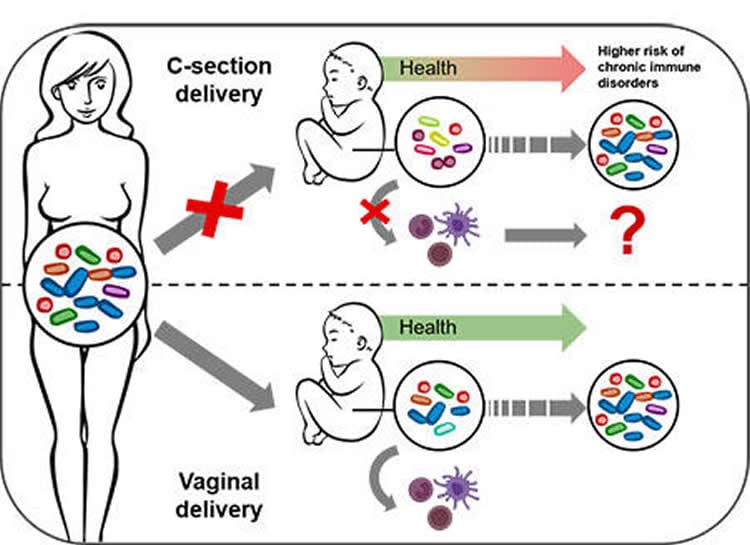

Summary: Findings may explain why children born by C-sections are more prone to suffer from chronic immune system diseases that those born via vaginal birth, researchers report.

Source: University of Luxembourg.

Together with colleagues from Sweden and Luxembourg, scientists from the Luxembourg Centre for Systems Biomedicine (LCSB) of the University of Luxembourg have observed that, during a natural vaginal birth, specific bacteria from the mother’s gut are passed on to the baby and stimulate the baby’s immune responses.

This transmission is impacted in children born by caesarean section. “This may explain why, epidemiologically speaking, caesarean-born children suffer more frequently from chronic, immune system-linked diseases compared to babies born vaginally,” says the head of the study Associate Prof. Paul Wilmes. His team has now published its results in the open access journal Nature Communications.

Humans are born germ-free. Yet, birth is normally the time when vitally important bacteria start to colonise the body including the gut, skin and lungs. Researchers have long suspected that this early colonisation sets the course for one’s later health.

It could be, however, that a caesarean section prevents certain bacteria, ordinarily interacting with the baby’s immune system, from being passed on from the mother to the new-born. Paul Wilmes, head of the Eco-Systems Biology research group at the LCSB, and his colleagues have now found the first evidence of this in a study of new-borns – half of whom were delivered by caesarean section.

Wilmes reports: “We find specific bacterial substances that stimulate the immune system in vaginally born babies. In contrast, the immune stimulation in caesarean children is much lower either because the bacterial triggers are present at much lower levels or other bacterial substances hamper these initial immune reactions to happen.”

Caesarean birth prevents important bacterial functions from being passed on. This change impacts immune stimulations during the first days of life and may explain why caesarean-born children suffer more frequently from chronic immune disorders.

This bacterial coloniser-immune system link – together with other factors – could explain why caesarean section babies are statistically more prone to develop allergies, chronic inflammatory diseases and metabolic diseases. “It could be that the immune system of these children is set on a different path early on,” suggests Paul Wilmes. “We now want to further investigate this link mechanistically and find ways by which we might replace the lacking maternal bacterial strains in caesarean-born babies, e.g. by administering probiotics.”

“Of course, it is already clear that we should not intervene too strongly in the birth process. Babies should only be delivered by caesarean section when it is medically necessary”, Paul Wilmes stresses. “We need to be aware that, in doing so, we are apparently intervening massively in the natural interactions between humans and bacteria.”

Funding: The study was supported by the Fondation André et Henriette Losch as well as by grants from the ATTRACT, CORE and AFR programmes of the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR). Additional funds were provided by the University of Luxembourg. Sample collection, processing and storage were co-funded by the Integrated BioBank of Luxembourg under the Personalised Medicine Consortium Diabetes programme.

Source: University of Luxembourg

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Linda Wampach.

Original Research: Open access research for “Birth mode is associated with earliest strain-conferred gut microbiome functions and immunostimulatory potential” by Linda Wampach, Anna Heintz-Buschart, Joëlle V. Fritz, Javier Ramiro-Garcia, Janine Habier, Malte Herold, Shaman Narayanasamy, Anne Kaysen, Angela H. Hogan, Lutz Bindl, Jean Bottu, Rashi Halder, Conny Sjöqvist, Patrick May, Anders F. Andersson, Carine de Beaufort & Paul Wilmes in Nature Communications. Published November 30 2018.

doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07631-x

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]University of Luxembourg”Altered Microbiome Post Cesarean Section Impacts Baby’s Immune System.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 30 November 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/c-section-immune-microbiome-10279/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]University of Luxembourg(2018, November 30). Altered Microbiome Post Cesarean Section Impacts Baby’s Immune System. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved November 30, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/c-section-immune-microbiome-10279/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]University of Luxembourg”Altered Microbiome Post Cesarean Section Impacts Baby’s Immune System.” https://neurosciencenews.com/c-section-immune-microbiome-10279/ (accessed November 30, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Birth mode is associated with earliest strain-conferred gut microbiome functions and immunostimulatory potential

The rate of caesarean section delivery (CSD) is increasing worldwide. It remains unclear whether disruption of mother-to-neonate transmission of microbiota through CSD occurs and whether it affects human physiology. Here we perform metagenomic analysis of earliest gut microbial community structures and functions. We identify differences in encoded functions between microbiomes of vaginally delivered (VD) and CSD neonates. Several functional pathways are over-represented in VD neonates, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis. We link these enriched functions to individual-specific strains, which are transmitted from mothers to neonates in case of VD. The stimulation of primary human immune cells with LPS isolated from early stool samples of VD neonates results in higher levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interleukin 18 (IL-18). Accordingly, the observed levels of TNF-α and IL-18 in neonatal blood plasma are higher after VD. Taken together, our results support that CSD disrupts mother-to-neonate transmission of specific microbial strains, linked functional repertoires and immune-stimulatory potential during a critical window for neonatal immune system priming.