Summary: Fenofibrate, an FDA-approved drug commonly used to treat high cholesterol, activated support cells around sensory neurons in mouse models of spinal cord injury, helping them regrow twice as fast as a placebo.

Source: WUSTL

A spinal cord injury damages the lines of communication between the body and brain, impeding the signals that drive movement and sensation. Injured motor and sensory neurons in the central nervous system — the brain and spinal cord — have limited ability to heal, so people who survive such injuries can be left with chronic paralysis, numbness and pain.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a drug that helps sensory neurons in the central nervous system heal. Neurons are surrounded by support cells that protect and nurture them.

In this study, the researchers gave mice with injured sensory neurons a drug called fenofibrate that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat high cholesterol. The drug activated the support cells surrounding sensory neurons and helped them regrow about twice as fast as sensory neurons in mice that received a placebo.

The study is available online in eLife.

“When people think of spinal cord injury, they tend to think of paralysis, but there are a lot of problems with sensory processing and pain after spinal cord injury as well,” said senior author Valeria Cavalli, PhD, the Robert E. and Louise F. Dunn Professor of Biomedical Research and a professor of neuroscience.

“Addressing those sensory issues could go a long way toward improving quality of life for survivors. Our data indicate that fenofibrate has the potential to activate these support cells and improve recovery, which means we could potentially repurpose this FDA-approved compound to help restore sensory function after nerve injuries.”

Unlike neurons in the brain or spinal cord, sensory nerves in the periphery of the body heal after injury, which is why a gash on your leg doesn’t leave part of your leg permanently numb. To understand why regeneration occurs in the peripheral but not the central nervous system, Cavalli studies a unique cell type that spans both systems: sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglia.

The cell bodies of such neurons bundle together into a structure known as a ganglion that sits just outside the spinal cord. A long, thin arm called an axon branches out from each cell body in opposite directions, with one branch heading into the central nervous system via the spinal cord and the other becoming part of the peripheral nervous system as it descends into the body.

Despite being two parts of the same cell, the peripheral and central axonal branches do not respond identically after injury. The peripheral parts regrow and recover much faster and more completely than the central ones.

Cavalli and first author Oshri Avraham, PhD, a staff scientist, suspected that the differences in regeneration between the two branches may come down to differences between the behavior of support cells in response to injury to the central versus peripheral axon branches.

To investigate that possibility, the researchers compared gene expression in five kinds of support cells in the ganglion, after injury to the peripheral and central branches of the sensory neuron. They found that the patterns of gene expression in the support cells differed depending on which part of the neuron they injured.

Most notably, so-called satellite glial cells ramped up expression of a set of genes known as the PPAR-alpha pathway — famous for its role in fat metabolism — only after injury in the peripheral axon branch. The pathway was not turned up after injury to central axonal branches, and was actually dialed down after spinal cord injury in the central nervous system.

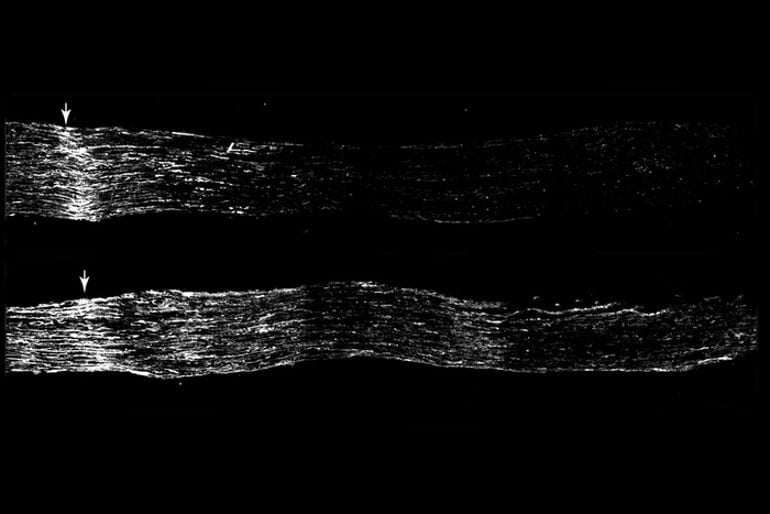

To Cavalli and Avraham, this observation suggested that the PPAR-alpha pathway may promote regeneration. To find out, they fed mice fenofibrate — a drug that activates PPAR alpha — for two weeks before injuring the mice’s sensory axon branch heading into the central nervous system. Three days after the injury, the central branches of the sensory neuron axons had regrown about twice as much in the mice that had received fenofibrate than in those that had received a placebo.

“PPAR alpha is only expressed in satellite glial cells, not in neurons, so these results tell us that targeting these support cells can improve regeneration and potentially relieve sensory symptoms like pain,” Cavalli said. “It gives us an additional tool to design therapies to restore function after nerve injuries. We haven’t fixed spinal cord injury, but we’re one step closer to figuring out how to do it.”

Cavalli and colleagues are now planning experiments to combine fenofibrate with other experimental regeneration-promoting therapies targeting neurons or other aspects of the central nervous system to further enhance regeneration.

About this neuropharmacology research news

Author: Judy Martin Finch

Source: WUSTL

Contact: Judy Martin Finch – WUSTL

Image: The image is credited to Rui Feng

Original Research: Open access.

“Profiling sensory neuron microenvironment after peripheral and central axon injury reveals key pathways for neural repair” by Oshri Avraham, Rui Feng, Eric Edward Ewan, Justin Rustenhoven, Guoyan Zhao, Valeria Cavalli. eLife

Abstract

Profiling sensory neuron microenvironment after peripheral and central axon injury reveals key pathways for neural repair

Sensory neurons with cell bodies in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) represent a useful model to study axon regeneration. Whereas regeneration and functional recovery occurs after peripheral nerve injury, spinal cord injury or dorsal root injury is not followed by regenerative outcomes.

Regeneration of sensory axons in peripheral nerves is not entirely cell autonomous. Whether the DRG microenvironment influences the different regenerative capacities after injury to peripheral or central axons remains largely unknown.

To answer this question, we performed a single-cell transcriptional profiling of mouse DRG in response to peripheral (sciatic nerve crush) and central axon injuries (dorsal root crush and spinal cord injury). Each cell type responded differently to the three types of injuries. All injuries increased the proportion of a cell type that shares features of both immune cells and glial cells.

A distinct subset of satellite glial cells (SGC) appeared specifically in response to peripheral nerve injury. Activation of the PPARα signaling pathway in SGC, which promotes axon regeneration after peripheral nerve injury, failed to occur after central axon injuries. Treatment with the FDA-approved PPARα agonist fenofibrate increased axon regeneration after dorsal root injury.

This study provides a map of the distinct DRG microenvironment responses to peripheral and central injuries at the single-cell level and highlights that manipulating non-neuronal cells could lead to avenues to promote functional recovery after CNS injuries or disease.