Summary: A new study reveals that cognitive tests in infancy can modestly predict intelligence three decades later. Researchers followed over 1,000 twins from seven months of age, measuring behaviors like vocalization and novelty preference to assess early cognition.

By age 30, those early assessments accounted for about 13% of the variance in adult cognitive scores, with environment in the first years of life having a notable impact. While genetics still played a major role, the study highlights how early-life environments influence cognitive outcomes across a lifetime.

Key Facts:

- Long-Term Insight: Infant cognitive tests predicted up to 13% of cognitive performance at age 30.

- Environmental Impact: Environmental influences before age one explained 10% of adult cognitive variability.

- Strongest Signals: Novelty preference and task orientation in infancy were key predictors.

Source: University of Colorado

Watching a baby babble, play and interact with others can provide useful insight into what their cognitive ability might be like decades later, according to new University of Colorado Boulder research published in the journal PNAS.

The study of more than 1,000 twins found that tests as early as 7 months of age can help predict performance on cognitive measures at age 30. It also found that an infant’s environment plays a more significant role in shaping life-long cognition than scientists realized. It could even influence risk of dementia later in life, the authors said.

“Our findings highlight the enduring consequences of the very early childhood environment on cognitive ability and suggest that early life is a critical developmental period that we should be paying attention to,” said lead author Daniel Gustavson, assistant research professor at the Institute for Behavioral Genetics (IBG).

What twins can teach us

Similar to “IQ,” general cognitive ability (GCA) is a single, composite measure of a person’s capacity to learn, reason, understand and problem-solve.

Prior research has shown that much of our GCA is established by childhood. Give an 8-year-old a battery of tests to determine their GCA and their score will look remarkably similar at age 30. Measures of intelligence at age 20 are highly correlated with those at age 62, and IQ doesn’t change much between age 11 and 90.

But few scientists have looked back further to see what — if anything—signals in infancy can tell us about cognition in adulthood and old age.

Gustavson and senior author Chandra Reynolds, a professor of psychology and neuroscience, looked at data from 1,098 participants in the Colorado Longitudinal Twin Study. IBG launched the study in 1985, enrolling baby twins from Colorado’s Front Range to assess the role that genes vs. environment play in various aspects of development.

Researchers have since collected reams of data, via periodic laboratory samples, home visits, surveys, interviews and behavioral tests.

“We have co-authors on this paper who have been involved since the start and watched these twins grow up,” said Gustavson.

As early as 7 months old, researchers assessed seven measures of cognition, including vocalization, ability to stay on task, and “novelty preference” — whether the infants preferred to play with new toys over ones they were familiar with.

Age-appropriate cognitive assessments have been done at five points, so far.

The team found that looking at cognitive tests in infancy could predict about 13% of the variance in scores at age 30.

Two measures —novelty preference and task orientation—were the strongest predictors. This early life “signal” is not huge, the authors note.

“We certainly do not want to imply that cognition is somehow fixed by seven months old,” Gustavson said. “But the idea that a very simple test in infancy can help predict the results of a very complicated cognitive test taken 30 years later is exciting.”

Nature, nurture or both?

To explore what role genetics vs. environment plays, the study compared GCA score differences between identical twins, who share 100% of their genes, and fraternal twins, who only share half of their genes. In general, if there is greater similarity among identical twins than fraternal twins, this suggests that genes play a strong role in that trait.

They also analyzed the twins’ DNA collected via blood or saliva.

As expected, genes played a big role in influencing general cognitive ability, with genetic influences measured by age 7 accounting for about half of the variation in scores at age 30.

But environment also had a significant and lasting impact.

“One of the most exciting findings was that 10% of the variability in adult cognitive ability was explained by environmental influences before year one or two,” said Gustavson.

The older the children got, the more influence genes had and the less environment had.

“This suggests that even the pre-preschool environment matters,” Gustavson said.

Reynolds, who studies age-related diseases including Alzheimer’s and dementia, says the findings could have implications not only for how youth do in school or how adults perform at work but also how prone they may be to age-related cognitive decline.

“Cognitive aging is a life-long process, not just something that begins in mid-life,” she said. “It could be that certain interventions, like strong educational foundations in early life could help maximize what people are capable of and help them keep that cognitive gas in the tank for as long as possible.”

A polygenic score for intelligence

The study also confirms that “polygenic scores” can be a useful tool.

Polygenic scores are single numbers that aggregate a person’s genetic variants to estimate predisposition to a trait, like intelligence.

“There are thousands of genes that influence intelligence, so you are never going to find an ‘intelligence gene’, but we have found many with tiny effects that when put together can have an impact,” Gustavson said.

For the study, the researchers used genetic data from nearly 1 million individuals gathered via large datasets like 23 and Me to give each of the adult twins a polygenic score based on their own DNA, for cognitive ability.

Remarkably, the twins’ scores closely matched what would be expected based on their tests when they were babies.

“Studies like ours show us that both family-based and genomic-based datasets are valuable in answering questions about how genetic and environmental influences change across the lifespan,” said Gustavson.

About this neurodevelopment and Intelligence research news

Author: Lisa Marshall

Source: University of Colorado

Contact: Lisa Marshall – University of Colorado

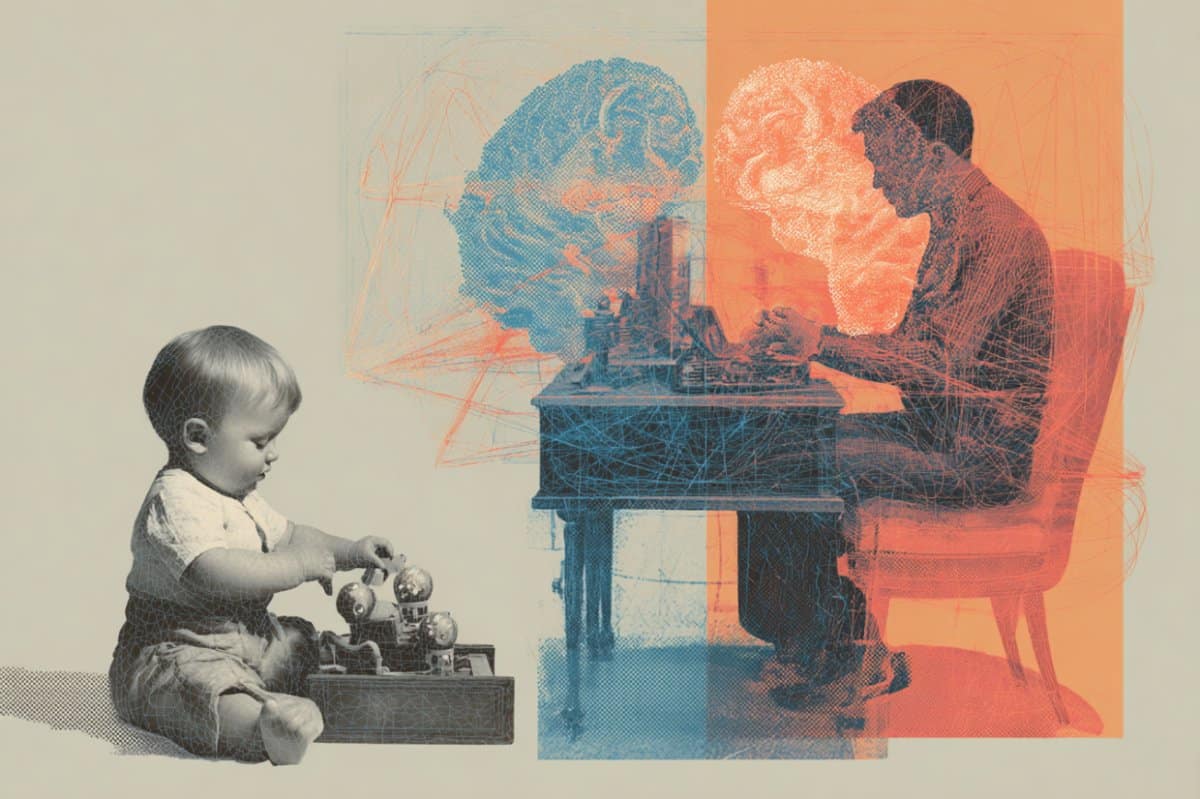

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Closed access.

“Stability of general cognitive ability from infancy to adulthood: A combined twin and genomic investigation” by Daniel Gustavson et al. PNAS

Abstract

Stability of general cognitive ability from infancy to adulthood: A combined twin and genomic investigation

Measures of general cognitive ability (GCA) are highly stable from adolescence onward, particularly at the level of genetic influences.

In contrast, measurement of GCA in early life (before 3 y old) is less reliable and less is known about the stability of GCA across this period, including its relation to adult GCA.

Using data from the Colorado Longitudinal Twin study (N = 1,098), we examined the stability of GCA measures across 5 time-points (years 1 to 2, 3, 7, 16, and 29), including how an array of cognitive measures given at 7 and 9 mo relate to later GCA.

We then examined the genetic and environmental stability of GCA across the first 30 y of life using complementary methods: twin analyses and polygenic scores (PGSs).

Two infant cognition measures, object novelty and tester-rated task orientation, predicted GCA in adulthood (r = 0.16 and 0.18, respectively).

Correlational analyses were consistent with a pattern of increasing stability across development for GCA measures between year 1 to 2 and adulthood (r = 0.39 to 0.85).

Subsequent twin analyses revealed that 22% of variance in adulthood GCA was captured by genetic influences on GCA from year 3 or earlier, with an additional 10% explained by shared environmental influences on GCA at year 1 to 2. PGSs for adulthood GCA and educational attainment predicted GCA from 1 to 2 y onward (βs = 0.09 to 0.44) but not infant cognition.

Findings suggest that genetic and environmental influences on GCA demonstrate considerable stability as early as age 3 y, but that measures of infant cognition are less predictive of later cognitive ability.