Summary: Researchers implicate dopamine in human bonding and attachments.

Source: Northeastern University.

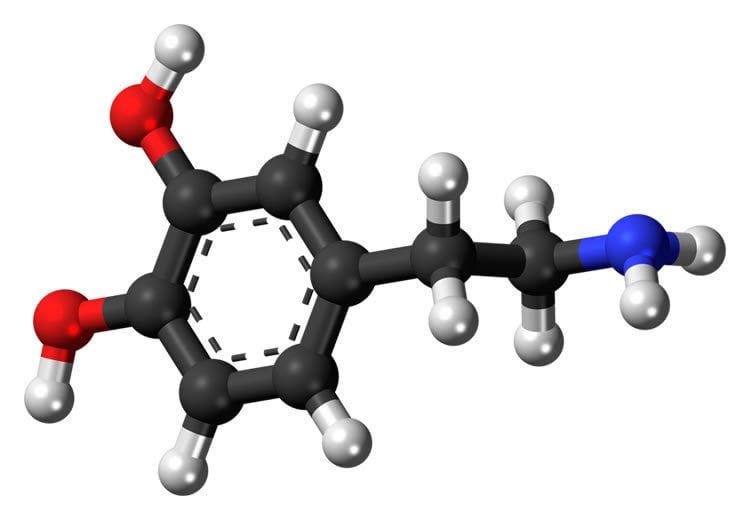

New research finds that dopamine is involved in human bonding.

In new research published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Northeastern University psychology professor Lisa Feldman Barrett found, for the first time, that the neurotransmitter dopamine is involved in human bonding, bringing the brain’s reward system into our understanding of how we form human attachments. The results, based on a study with 19 mother-infant pairs, have important implications for therapies addressing postpartum depression as well as disorders of the dopamine system such as Parkinson’s disease, addiction, and social dysfunction.

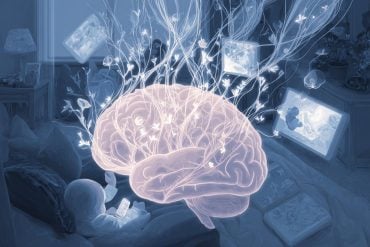

“The infant brain is very different from the mature adult brain–it is not fully formed,” says Barrett, University Distinguished Professor of Psychology and author of the forthcoming book How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. “Infants are completely dependent on their caregivers. Whether they get enough to eat, the right kind of nutrients, whether they’re kept warm or cool enough, whether they’re hugged enough and get enough social attention, all these things are important to normal brain development. Our study shows clearly that a biological process in one person’s brain, the mother’s, is linked to behavior that gives the child the social input that will help wire his or her brain normally. That means parents’ ability to keep their infants cared for leads to optimal brain development, which over the years results in better adult health and greater productivity.”

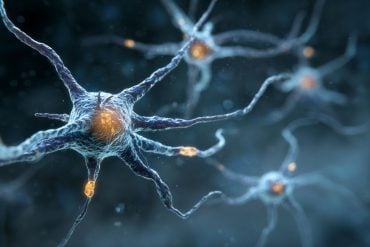

To conduct the study, the researchers turned to a novel technology: a machine capable of performing two types of brain scans simultaneously–functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, and positron emission tomography, or PET.

fMRI looks at the brain in slices, front to back, like a loaf of bread, and tracks blood flow to its various parts. It is especially useful in revealing which neurons are firing frequently as well as how different brain regions connect in networks. PET uses a small amount of radioactive chemical plus dye (called a tracer) injected into the bloodstream along with a camera and a computer to produce multidimensional images to show the distribution of a specific neurotransmitter, such as dopamine or opioids.

Barrett’s team focused on the neurotransmitter dopamine, a chemical that acts in various brain systems to spark the motivation necessary to work for a reward. They tied the mothers’ level of dopamine to her degree of synchrony with her infant as well as to the strength of the connection within a brain network called the medial amygdala network that, within the social realm, supports social affiliation.

“We found that social affiliation is a potent stimulator of dopamine,” says Barrett. “This link implies that strong social relationships have the potential to improve your outcome if you have a disease, such as depression, where dopamine is compromised. We already know that people deal with illness better when they have a strong social network. What our study suggests is that caring for others, not just receiving caring, may have the ability to increase your dopamine levels.”

Before performing the scans, the researchers videotaped the mothers at home interacting with their babies and applied measurements to the behaviors of both to ascertain their degree of synchrony. They also videotaped the infants playing on their own.

Once in the brain scanner, each mother viewed footage of her own baby at solitary play as well as an unfamiliar baby at play while the researchers measured dopamine levels, with PET, and tracked the strength of the medial amygdala network, with fMRI.

The mothers who were more synchronous with their own infants showed both an increased dopamine response when viewing their child at play and stronger connectivity within the medial amygdala network. “Animal studies have shown the role of dopamine in bonding but this was the first scientific evidence that it is involved in human bonding,” says Barrett. “That suggests that other animal research in this area could be directly applied to humans as well.”

The findings, says Barrett, are “cautionary.” “They have the potential to reveal how the social environment impacts the developing brain,” she says. “People’s future health, mental and physical, is affected by the kind of care they receive when they are babies. If we want to invest wisely in the health of our country, we should concentrate on infants and children, eradicating the adverse conditions that interfere with brain development.”

Source: John O’Neill – Northeastern University

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Dopamine in the medial amygdala network mediates human bonding” by Shir Atzil, Alexandra Touroutoglou, Tali Rudy, Stephanie Salcedo, Ruth Feldman, Jacob M. Hooker, Bradford C. Dickerson, Ciprian Catana, and Lisa Feldman Barrett in PNAS. Published online February 13 2017 doi:10.1073/pnas.1612233114

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Northeastern University “The Brain Chemistry Behind Human Bonding Revealed.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 17 February 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/dopamine-bonding-chemistry-6126/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Northeastern University (2017, February 17). The Brain Chemistry Behind Human Bonding Revealed. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved February 17, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/dopamine-bonding-chemistry-6126/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Northeastern University “The Brain Chemistry Behind Human Bonding Revealed.” https://neurosciencenews.com/dopamine-bonding-chemistry-6126/ (accessed February 17, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Dopamine in the medial amygdala network mediates human bonding

Research in humans and nonhuman animals indicates that social affiliation, and particularly maternal bonding, depends on reward circuitry. Although numerous mechanistic studies in rodents demonstrated that maternal bonding depends on striatal dopamine transmission, the neurochemistry supporting maternal behavior in humans has not been described so far. In this study, we tested the role of central dopamine in human bonding. We applied a combined functional MRI-PET scanner to simultaneously probe mothers’ dopamine responses to their infants and the connectivity between the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), the amygdala, and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which form an intrinsic network (referred to as the “medial amygdala network”) that supports social functioning. We also measured the mothers’ behavioral synchrony with their infants and plasma oxytocin. The results of this study suggest that synchronous maternal behavior is associated with increased dopamine responses to the mother’s infant and stronger intrinsic connectivity within the medial amygdala network. Moreover, stronger network connectivity is associated with increased dopamine responses within the network and decreased plasma oxytocin. Together, these data indicate that dopamine is involved in human bonding. Compared with other mammals, humans have an unusually complex social life. The complexity of human bonding cannot be fully captured in nonhuman animal models, particularly in pathological bonding, such as that in autistic spectrum disorder or postpartum depression. Thus, investigations of the neurochemistry of social bonding in humans, for which this study provides initial evidence, are warranted.

“Dopamine in the medial amygdala network mediates human bonding” by Shir Atzil, Alexandra Touroutoglou, Tali Rudy, Stephanie Salcedo, Ruth Feldman, Jacob M. Hooker, Bradford C. Dickerson, Ciprian Catana, and Lisa Feldman Barrett in PNAS. Published online February 13 2017 doi:10.1073/pnas.1612233114