Summary: According to researchers, being in a challenging situation makes it more difficult for people to understand where they are or what is happening around them.

Source: Frontiers.

Research published today in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience shows that challenging situations make it harder to understand where you are and what’s happening around you. A team of researchers showed participants video clips of a positive, a negative and a neutral situation. After watching the challenging clips — whether positive or negative — the participants performed worse on tests measuring their unconscious ability to acquire information about where and when things happen. This suggests that challenging situations cause the brain to drop nuanced, context-based cognition in favor of reflexive action.

Previous research suggests that long-term memories formed under stress lack the context and peripheral details encoded by the hippocampus, making false alarms and reflexive reactions more likely. These context details are necessary for situating yourself in space and time, so struggling to acquire them has implications for decision-making in the moment as well as in memory formation.

The research team, led by Thomas Maran, Marco Furtner and Pierre Sachse, investigated the short-term effects of challenging experiences on acquiring these context details. The team also investigated whether experiences coded as positive produced the same response as those coded as negative.

“We aimed to make this change measurable on a behavioral level, to draw conclusions on how behavior in everyday life and challenging situations is affected by variations in arousal,” Thomas Maran explains.

The researchers predicted that study participants would be less able to acquire spatial and sequential context after watching challenging clips, and that their performance would worsen the same way faced with either a positive or a negative clip. To test this, they used clips of film footage used previously to elicit reactions in stress studies: one violent scene (which participants experienced as negative), one sex scene (which participants experienced as positive), and one neutral control scene.

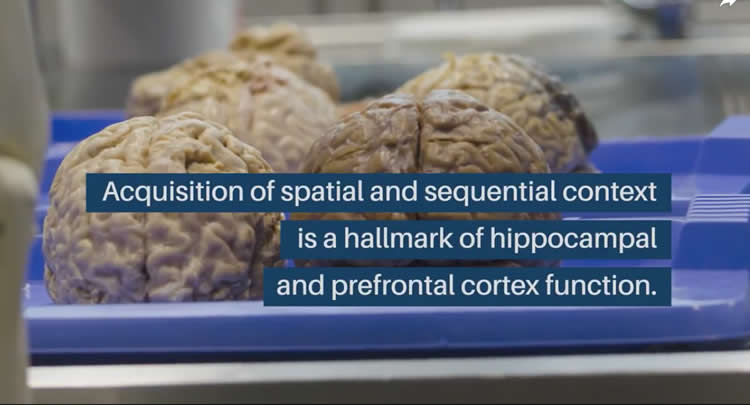

Immediately after watching the clips, two groups of participants performed tasks designed to test their ability to acquire either spatial or sequential context. Both the sex scene and violent scene disrupted participants’ ability to memorize where objects had been and notice patterns in two different tasks, compared to the neutral scene. This supports the hypothesis that challenging situations — positive or negative — cause the brain to drop nuanced, context-based cognition in favor of reflexive action.

So if challenging situations decrease the ability to pick up on context cues, how does this happen? The researchers suggest that the answer may lie in the hippocampus region of the brain — although they caution that since no neurophysiological techniques were applied in this study, this can’t be proven. Since existing evidence supports the idea that the hippocampus is deeply involved in retrieving and reconstructing spatial and temporal details, downgrading this function when faced with a potentially dangerous situation could stop this context acquisition and achieve the effect seen in this behavioral study. Reflexive reactions are less complex and demanding, and might stop individuals from making decisions based on unreliable information from unpredictable surroundings.

“Changes in cognition during high arousal states play an important role in psychopathology,” Thomas Maran explains, outlining his hopes for the future use of this research. He considers that the evidence provided by this study may have important therapeutic and forensic applications. It also gives a better basis for understanding reactions to challenging situations — from witnessing a crime to fighting on a battlefield — and the changes in the brain that make those reactions happen.

Funding: The research was supported by the Association for the Promotion of the Scientific Education, University of Innsbruck.

Source: Emma Duncan – Frontiers

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is adapted from the Frontiers video.

Video Source: Video credited to Frontiers.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Lost in Time and Space: States of High Arousal Disrupt Implicit Acquisition of Spatial and Sequential Context Information” by Thomas Maran, Pierre Sachse, Markus Martini, Barbara Weber, Jakob Pinggera, Stefan Zuggal and Marco Furtner in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. Published online November 9 2017 doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00206

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Frontiers “How Challenges Change the Way You Think.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 10 November 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/challenge-cognition-7908/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Frontiers (2017, November 10). How Challenges Change the Way You Think. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved November 10, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/challenge-cognition-7908/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Frontiers “How Challenges Change the Way You Think.” https://neurosciencenews.com/challenge-cognition-7908/ (accessed November 10, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Lost in Time and Space: States of High Arousal Disrupt Implicit Acquisition of Spatial and Sequential Context Information

Biased cognition during high arousal states is a relevant phenomenon in a variety of topics: from the development of post-traumatic stress disorders or stress-triggered addictive behaviors to forensic considerations regarding crimes of passion. Recent evidence indicates that arousal modulates the engagement of a hippocampus-based “cognitive” system in favor of a striatum-based “habit” system in learning and memory, promoting a switch from flexible, contextualized to more rigid, reflexive responses. Existing findings appear inconsistent, therefore it is unclear whether and which type of context processing is disrupted by enhanced arousal. In this behavioral study, we investigated such arousal-triggered cognitive-state shifts in human subjects. We validated an arousal induction procedure (three experimental conditions: violent scene, erotic scene, neutral control scene) using pupillometry (Preliminary Experiment, n = 13) and randomly administered this method to healthy young adults to examine whether high arousal states affect performance in two core domains of contextual processing, the acquisition of spatial (spatial discrimination paradigm; Experiment 1, n = 66) and sequence information (learned irrelevance paradigm; Experiment 2, n = 84). In both paradigms, spatial location and sequences were encoded incidentally and both displacements when retrieving spatial position as well as the predictability of the target by a cue in sequence learning changed stepwise. Results showed that both implicit spatial and sequence learning were disrupted during high arousal states, regardless of valence. Compared to the control group, participants in the arousal conditions showed impaired discrimination of spatial positions and abolished learning of associative sequences. Furthermore, Bayesian analyses revealed evidence against the null models. In line with recent models of stress effects on cognition, both experiments provide evidence for decreased engagement of flexible, cognitive systems supporting encoding of context information in active cognition during acute arousal, promoting reduced sensitivity for contextual details. We argue that arousal fosters cognitive adaptation towards less demanding, more present-oriented information processing, which prioritizes a current behavioral response set at the cost of contextual cues. This transient state of behavioral perseverance might reduce reliance on context information in unpredictable environments and thus represent an adaptive response in certain situations.

“Lost in Time and Space: States of High Arousal Disrupt Implicit Acquisition of Spatial and Sequential Context Information” by Thomas Maran, Pierre Sachse, Markus Martini, Barbara Weber, Jakob Pinggera, Stefan Zuggal and Marco Furtner in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. Published online November 9 2017 doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00206