Summary: When the hormone allopregnanolone (ALLO) abruptly decreases or stops during pregnancy, children are more likely to develop autism. Researchers report a single ALLO injection during pregnancy can avert the brain abnormalities and social behaviors associated with ASD in experimental mouse models of autism.

Source: Children’s National Hospital

A study in experimental models suggests that allopregnanolone, one of many hormones produced by the placenta during pregnancy, is so essential to normal fetal brain development that when provision of that hormone decreases or stops abruptly – as occurs with premature birth – offspring are more likely to develop autism-like behaviors. A Children’s National Hospital research team reports the findings Oct. 20, 2019, at the Neuroscience 2019 annual meeting.

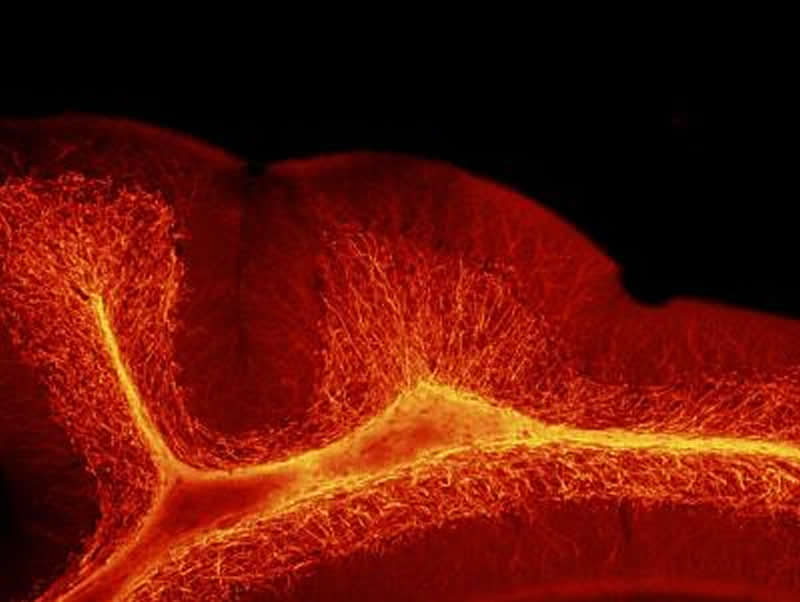

“To our knowledge, no other research team has studied how placental allopregnanolone (ALLO) contributes to brain development and long-term behaviors,” says Claire-Marie Vacher, Ph.D., lead author. “Our study finds that targeted loss of ALLO in the womb leads to long-term structural alterations of the cerebellum – a brain region that is essential for motor coordination, balance and social cognition – and increases the risk of developing autism,” Vacher says.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1 in 10 infants is born preterm, before 37 weeks gestation; and 1 in 59 children has autism spectrum disorder.

In addition to presenting the abstract, on Monday, Oct. 21, Anna Penn, M.D., Ph.D., the abstract’s senior author, will discuss the research with reporters during a Neuroscience 2019 news conference. This Children’s National abstract is among 14,000 abstracts submitted for the meeting, the world’s largest source of emerging news about brain science and health.

ALLO production by the placenta rises in the second trimester of pregnancy, and levels of the neurosteroid peak as fetuses approach full term.

To investigate what happens when ALLO supplies are disrupted, a research team led by Children’s National created a novel transgenic preclinical model in which they deleted a gene essential in ALLO synthesis. When production of ALLO in the placentas of these experimental models declines, offspring had permanent neurodevelopmental changes in a sex- and region-specific manner.

“From a structural perspective, the most pronounced cerebellar abnormalities appeared in the cerebellum’s white matter,” Vacher adds. “We found increased thickness of the myelin, a lipid-rich insulating layer that protects nerve fibers. From a behavioral perspective, male offspring whose ALLO supply was abruptly reduced exhibited increased repetitive behavior and sociability deficits – two hallmarks in humans who have autism spectrum disorder.”

On a positive note, providing a single ALLO injection during pregnancy was enough to avert both the cerebellar abnormalities and the aberrant social behaviors in experimental models.

The research team is now launching a new area of research focus they call “neuroplacentology” to better understand the role of placenta function on fetal and newborn brain development.

“Our team’s data provide exciting new evidence that underscores the importance of placental hormones on shaping and programming the developing fetal brain,” Vacher notes.

Source:

Children’s National Hospital

Media Contacts:

Diedtra Henderson – Children’s National Hospital

Image Source:

The image is credited to Children’s National Hospital.

Original Research: The study will be presented at Neuroscience 2019 in Chicago.