A study, performed in mice and utilizing post-mortem samples of brains from patients with Alzheimer’s disease, found that a single event of a moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) can disrupt proteins that regulate an enzyme associated with Alzheimer’s. The paper, published in The Journal of Neuroscience, identifies the complex mechanisms that result in a rapid and robust post-injury elevation of the enzyme, BACE1, in the brain. These results may lead to the development of a drug treatment that targets this mechanism to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

“A moderate-to-severe TBI, or head trauma, is one of the strongest environmental risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. A serious TBI can lead to a dysfunction in the regulation of the enzyme BACE1. Elevations of this enzyme cause elevated levels of amyloid-beta, the key component of brain plaques associated with senility and Alzheimer’s disease,” said first author Kendall Walker, PhD, postdoctoral associate in the department of neuroscience at Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM).

Building on her previous work, neuroscientist Giuseppina Tesco, MD, PhD, of Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM), led a research team that first used an in vivo model to determine how a single episode of TBI could alter the brain. In the acute phase (first two days) following injury, levels of two intracellular trafficking proteins (GGA1 and GGA3) were reduced, and an elevation of BACE1 enzyme level was observed.

Next, in an analysis of post-mortem brain samples from patients with Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers found that GGA1 and GGA3 levels were reduced while BACE1 levels were elevated in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients compared to the brains of people without Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting a possible inverse association.

In an additional experiment using a mouse strain genetically modified to express the reduced level of GGA3 that was observed in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients, the team found that one week following traumatic brain injury, BACE1 and amyloid-beta levels remained elevated even when GGA1 levels had returned to normal. The research suggests that reduced levels of GGA3 were solely responsible for the increase in BACE 1 levels and therefore the sustained amyloid-beta production observed in the sub-acute phase, or seven days, after injury.

“When the proteins are at normal levels, they work as a clean-up crew for the brain by regulating the removal of BACE1 enzymes and facilitating their transport to lysosomes within brain cells, an area of the cell that breaks down and removes excess cellular material. BACE1 enzyme levels may be stabilized when levels of the two proteins are low, likely caused by an interruption in the natural disposal process of the enzyme,” said Tesco, assistant professor of neuroscience at Tufts School of Medicine and member of the neuroscience program faculty at the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at Tufts.

“We found that GGA1 and GGA3 act synergistically to regulate BACE1 post-injury. The identification of this interaction may provide a drug target to therapeutically regulate the BACE1 enzyme and reduce the deposition of amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s patients,” she continued. “Our next steps are to confirm these findings in post-mortem brain samples from patients with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injuries.”

Moderate-to-severe TBIs are caused most often by traumas, such as severe falls or motor vehicle accidents, that result in a loss of consciousness. Not all traumas to the head result in a TBI. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each year 1.7 million people sustain a TBI. Concussions, the mildest form of a TBI, account for about 75% of all TBIs. Studies have linked repeated head trauma to brain disease and some previous studies have linked single events of brain trauma to brain disease, such as Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s disease currently affects as many as 5.1 million Americans and is the most common cause of dementia in adults age 65 and over.

Notes about this Alzheimer’s disease research

Additional authors on the study are Eugene Kang, MPH, research assistant in the department of neuroscience at TUSM; Michael Whalen, MD, PhD, Neuroscience Center and department of pediatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor at Harvard Medical School; and Yong Shen, MD, PhD, of the Center for Advanced Therapeutic Strategies for Brain Disorders at Roskamp Institute.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (#AG033016 and #AG025952), part of the National Institutes of Health; and a grant from the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund.

Contact: Jennifer Kritz – Tufts University School of Medicine

Source: Tufts University School of Medicine press release sent to Neuroscience News by Allison Barnes.

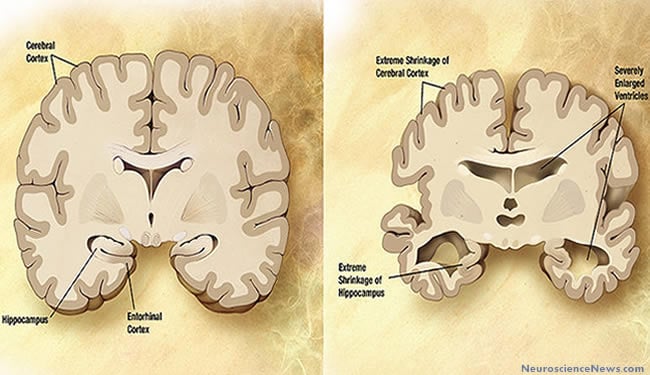

Image Source: Alzheimer’s disease brain vs the normal brain illustrations are in the public domain. Feel free to use.

Original Research: Abstract for “Depletion of GGA1 and GGA3 mediates post-injury elevation of BACE1” by Walker KR, Kang EL, Whalen MJ, Shen Y and Tesco G. in The Journal of Neuroscience online 25 July 2012 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-11.2012 (Abstract was not found at the Journal of Neuroscience. I’ll provide a link when it becomes available.)