Reducing fear and stress following a traumatic event could be as simple as providing a protein synthesis blocker to the brain, report a team of researchers from McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, McGill University, and Massachusetts General Hospital in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This is an important basic neuroscience finding that has the potential to have clinical implications for the way individuals with post traumatic stress disorder are treated,” said Vadim Bolshakov, PhD, director of the Cellular Neurobiology Laboratory at McLean Hospital. “We used a well-known behavioral paradigm that we think models PTSD, fear conditioning, to explore how fearful memories are formed. In our study, the level of fear exhibited by experimental subjects was significantly reduced as a result of decreased signal transfer between cells in the amygdala, a key brain region in fear-related behaviors.”

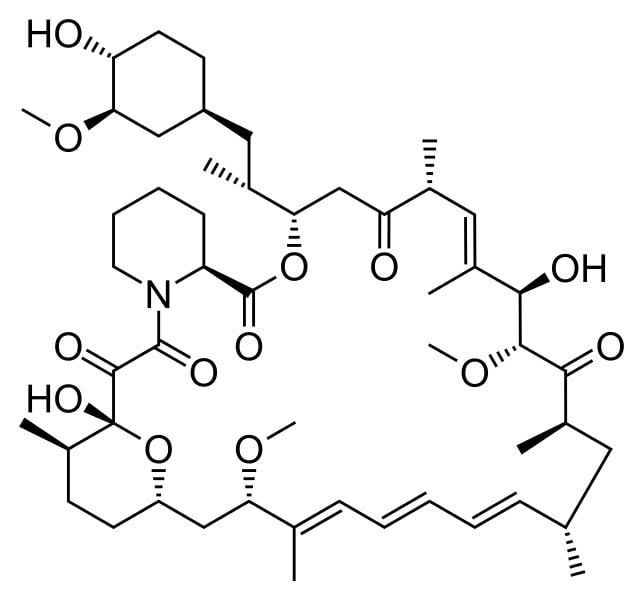

Influenced by the original findings of Karim Nader, PhD, professor of Psychology at McGill University, whose pioneering work showed that old memories should be un-stored in their brain after their recollection in order to last, Bolshakov’s team exposed rats to auditory stimulus that the animals learned to associate with a mildly traumatic event. After a single exposure to the training procedures, the rats exhibited fear during subsequent exposures to auditory stimuli. The researchers then provided the animals with rapamycin, a protein synthesis blocker, immediately after memory was retrieved in order to control bonding between the cells in the brain. The animals exhibited significantly less fear in response to the fear-invoking stimulus when retested the next day.

“The animals showed stereotypical signs of fear after the initial exposure to the auditory stimulus,” explained Nader, a co-author on the paper. “Following the administration of rapamycin, we show a significant decrease in fear, but not a complete elimination. We were surprised to note that activity between cells was significantly affected by postsynaptic mechanisms.”

The findings of this study, which was funded by a grant from the United States Department of Defense spearheaded by Roger Pitman, suggest that different plasticity rules within cells in the brain are recruited during the formation of the original fear memory and after fear memory was reactivated.

“Although further work at the molecular level needs to be completed, we are hopeful that this unexpected discovery is the foundation needed to identify ways in which we can better treat anxiety disorders in which fear condition plays a role, such as post-traumatic stress disorder,” said Bolshakov.

Notes about this PTSD and neuroscience research

Additional authors on this study include McLean Hospital’s Yan Li, PhD, Edward Meloni, PhD, William Carlezon, PhD, and Mohammed Milad and Roger Pitman, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital.

Contact: Cynthia Lee – McGill University

Source: McGill University press release

Image Source: Image is available in the public domain.

Original Research: Abstract for “Learning and reconsolidation implicate different synaptic mechanisms” by Yan Li, Edward G. Meloni, William A. Carlezon, Jr, Mohammed R. Milad, Roger K. Pitman, Karim Nader and Vadim Y. Bolshakov in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Published online March 4 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217878110