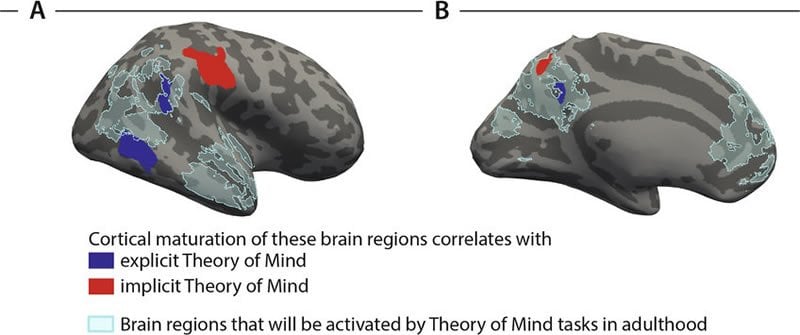

Summary: Study reveals two different brain structures are implicated in implicit and explicit theory of mind, and both regions mature at different ages to fulfill their function. The supramarginal gyrus matures earlier, enabling theory of mind to occur slightly earlier than believed. Full ability for theory of mind occurs at age four when the temporoparietal junction matures.

Source: Max Planck Institute

In order to understand what another person thinks and how he or she will behave we must take someone else’s perspective. This ability is referred to as Theory of Mind. Until recently, researchers were at odds concerning the age at which children are able to do such perspective taking. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, University College London, and the Social Neuroscience Lab Berlin shed new light on this question. Only 4-year-olds seem to be able to understand what others think.

The study reports that the unique ability to understand what others think emerges around 4 years of age because of the maturation of a specific brain network which enables this. Younger children are already capable of predicting others’ behaviour based on what they think, but the study shows that this prediction of behaviour relies on a different brain network. The brain seems to have two different systems to take another person’s perspective, and these mature at different rates.

The researchers investigated these relations in a sample of 3- to 4-year-old children with the help of a video clips that show a cat chasing a mouse. The cat watches the mouse hiding in one of two boxes. While the cat is away the mouse sneaks over to the other box, unnoticed by the cat. Thus, when the cat returns it should still believe that the mouse is in the first location.

Using eye-tracking technology, the scientists analysed the looking behaviour of their study participants and noticed: Both, the 3- and 4-year-olds expected the cat to go to the box where the mouse had originally been. That is, they predicted correctly where the cat was going to search for the mouse based on the cat’s belief.

A cat-and-mouse game

Where does the cat look for the mouse? When the scientists asked the children directly where the cat will search for the mouse, instead of looking at their gaze, 3-year-olds answered incorrectly. Only 4-years-olds succeeded.

Credit: Max Planck Institute.

Interestingly, when the scientists asked the children directly where the cat will search for the mouse, instead of looking at their gaze, 3-year-olds answered incorrectly. Only 4-years-olds succeeded. Control conditions ensured that this was not because the younger children misunderstood the question.

The reason for this discrepancy was a different one. The study shows that different brain structures were involved in verbal reasoning about what the cat thinks as opposed to non-verbal predictions of how the cat is going to act. The researchers refer to these brain structures as regions for implicit and explicit Theory of Mind. These cortical brain regions mature at different ages to fulfill their function. The supramarginal gyrus that supports non-verbal action prediction matures earlier, and is also involved in visual and emotional perspective taking. “This enables younger children to predict how people will act. The temporoparietal junction and precuneus through which we understand what others think – and not just what they feel and see or how they will act – only develops to fulfill this function at the age of 4 years”, first author Charlotte Grosse Wiesmann from the MPI CBS explains.

“In the first three years of life, children don’t seem to fully understand yet what others think“, says co-author Nikolaus Steinbeis from the University College London. “But there already seems to be a mechanism a basic form of perspective taking, by which very young children simply adopt the other’s view.”

Source:

Max Planck Institute

Media Contacts:

Verena Müller – Max Planck Institute

Image Source:

The image is credited to Max Planck Institute.

Original Research: The study will appear in PNAS.