Summary: A new study reports the brains of animals faced with disruptions in their social hierarchy produced far fewer new neurons in the hippocampus.

Source: Princeton.

People who experience job loss, divorce, death of a loved one or any number of life’s upheavals often adopt coping mechanisms to make the situation less traumatic.

While these strategies manifest as behaviors, a Princeton University and National Institutes of Health study suggests that our response to stressful situations originates from structural changes in our brain that allow us to adapt to turmoil.

A study conducted with adult rats showed that the brains of animals faced with disruptions in their social hierarchy produced far fewer new neurons in the hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for certain types of memory and stress regulation. Rats exhibiting this lack of brain-cell growth, or neurogenesis, reacted to the surrounding upheaval by favoring the company of familiar rats over that of unknown rats, according to a paper published in The Journal of Neuroscience.

The research is among the first to show that adult neurogenesis — or the lack thereof — has an active role in shaping social behavior and adaptation, said first author Maya Opendak, who received her Ph.D. in neuroscience from Princeton in 2015 and conducted the research as a graduate student. The preference for familiar rats may be an adaptive behavior triggered by the reduction in neuron production, she said.

“Adult-born neurons are thought to have a role in responding to novelty, and the hippocampus participates in resolving conflicts between different goals for use in decision-making,” said Opendak, who is now a postdoctoral research fellow of child and adolescent psychology at the New York University School of Medicine.

“Data from this study suggest that the reward of social novelty may be altered,” she said. “Indeed, sticking with a known partner rather than approaching a stranger may be beneficial in some circumstances.”

The findings also show that behavioral responses to instability may be more measured than scientists have come to expect, explained senior author Elizabeth Gould, Princeton’s Dorman T. Warren Professor of Psychology and department chair. Gould and her co-authors were surprised that the disrupted rats did not display any of the stereotypical signs of mental distress such as anxiety or memory loss, she said.

“Even in the face of what appears to be a very disruptive situation, there was not a negative pathological response but a change that could be viewed as adaptive and beneficial,” said Gould, who also is a professor of neuroscience in the Princeton Neuroscience Institute (PNI).

“We thought the animals would be more anxious, but we were making our prediction based on all the bias in the field that social disruption is always negative,” she said. “This research highlights the fact that organisms, including humans, are typically resilient in response to disruption and social instability.”

Co-authors on the paper include: Lily Offit, who received her bachelor’s degree in psychology and neuroscience from Princeton in 2015 and is now a research assistant at Columbia University Medical Center; Patrick Monari, a research specialist in PNI; Timothy Schoenfeld, a postdoctoral researcher at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) who received his Ph.D. in psychology and neuroscience from Princeton in 2012; Anup Sonti, an NIH researcher; and Heather Cameron, an NIH principal investigator of neuroplasticity.

The study is unusual for mimicking the true social structure of rats, Gould said. Rats live in structured societies that contain a single dominant male. The researchers placed rats into several groups consisting of four males and two females in to a large enclosure known as a visible burrow system. They then monitored the groups until the dominant rat in each one emerged and was identified. After a few days, the alpha rats of two communities were swapped, which reignited the contest for dominance in each group.

The rats from disrupted hierarchies displayed their preference for familiar fellows six weeks after those turbulent times, during which time neurogenesis had decreased by 50 percent, Opendak said. (Any neurons generated during the time of instability would take four to six weeks to be incorporated into the hippocampus’ circuitry, she said.)

When the researchers chemically restored adult neurogenesis in these rats, however, the animals’ interest in unknown rats returned to pre-disruption levels. At the same time, the researchers inhibited neuron growth in “naïve” transgenic rats that had not experienced social disruption. They found that the mere cessation of neurogenesis produced the same results as social disruption, particularly a preference for spending time with familiar rats.

“These results show that the reduction in new neurons is directly responsible for social behavior, something that hasn’t been shown before,” Gould said. The exact mechanism behind how lower neuron growth led to the behavior change is not yet clear, she said.

Bruce McEwen, professor of neuroendocrinology at The Rockefeller University, said that the research is a “major step forward” in efforts to explore the role of the dentate gyrus — a part of the hippocampus — in social behavior and antidepressant efficacy.

“The ventral dentate gyrus, where they found these effects, is now implicated in mood-related behaviors and the response to antidepressants,” said McEwen, who is familiar with the research but had no role in it.

“The connection to social behavior shown here is an important addition because social withdrawal is a key aspect of depression in humans, and the anterior hippocampus in humans is the homolog of the ventral hippocampus in rodents,” McEwen said. “Although there is no ‘animal model’ of human depression, the individual behaviors such as social avoidance, and brain changes such as neurogenesis, have been very useful in elucidating brain mechanisms in human depression.”

At this point, the extent to which the exact mechanism and behavioral changes the researchers observed in the rats would apply to humans is unknown, Gould and Opendak said. The study’s overall conclusion, however, that social disruption and instability lead to neurological changes that help us to better cope is likely universal, they said.

“Most people do experience some disruption in their lives, and resilience is the most typical response,” Gould said. “After all, if organisms always responded to stress with depression and anxiety, it’s unlikely early humans would have made it because life in the wild is very stressful.”

“For people who are exposed to social disruption frequently, our animal model suggests that these life events may be accompanied by long-term changes in brain function and social behavior,” Opendak said. “Although we hope that our findings may guide research on the mechanisms of resilience in humans, it is important as always to exercise caution when extrapolating these data across species.”

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH).

Source: Morgan Kelly – Princeton

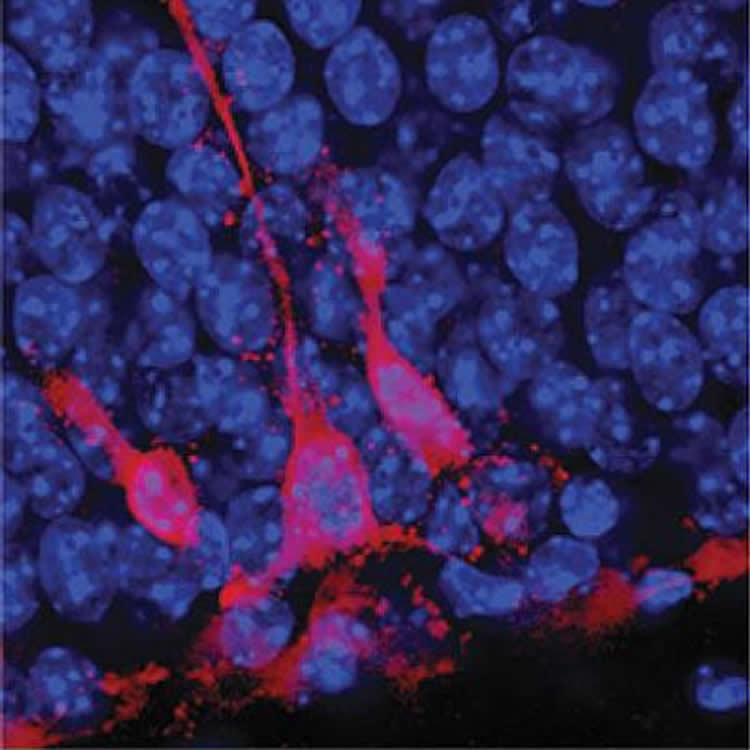

Image Source: This NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Maya Opendak, New York University.

Original Research: Abstract for “Lasting Adaptations in Social Behavior Produced by Social Disruption and Inhibition of Adult Neurogenesis” by Maya Opendak, Lily Offit, Patrick Monari, Timothy J. Schoenfeld, Anup N. Sonti, Heather A. Cameron, and Elizabeth Gould in Journal of Neuroscience. Published online June 29 2016 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4435-15.2016

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Princeton. “Brain Reduces Cell Production to Help Us Cope in Unstable Times.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 24 August 2016.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/trauma-neurogenesis-neurology-4904/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Princeton. (2016, August 24). Brain Reduces Cell Production to Help Us Cope in Unstable Times. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved August 24, 2016 from https://neurosciencenews.com/trauma-neurogenesis-neurology-4904/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Princeton. “Brain Reduces Cell Production to Help Us Cope in Unstable Times.” https://neurosciencenews.com/trauma-neurogenesis-neurology-4904/ (accessed August 24, 2016).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Lasting Adaptations in Social Behavior Produced by Social Disruption and Inhibition of Adult Neurogenesis

Research on social instability has focused on its detrimental consequences, but most people are resilient and respond by invoking various coping strategies. To investigate cellular processes underlying such strategies, a dominance hierarchy of rats was formed and then destabilized. Regardless of social position, rats from disrupted hierarchies had fewer new neurons in the hippocampus compared with rats from control cages and those from stable hierarchies. Social disruption produced a preference for familiar over novel conspecifics, a change that did not involve global memory impairments or increased anxiety. Using the neuropeptide oxytocin as a tool to increase neurogenesis in the hippocampus of disrupted rats restored preference for novel conspecifics to predisruption levels. Conversely, reducing the number of new neurons by limited inhibition of adult neurogenesis in naive transgenic GFAP–thymidine kinase rats resulted in social behavior similar to disrupted rats. Together, these results provide novel mechanistic evidence that social disruption shapes behavior in a potentially adaptive way, possibly by reducing adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT To investigate cellular processes underlying adaptation to social instability, a dominance hierarchy of rats was formed and then destabilized. Regardless of social position, rats from disrupted hierarchies had fewer new neurons in the hippocampus compared with rats from control cages and those from stable hierarchies. Unexpectedly, these changes were accompanied by changes in social strategies without evidence of impairments in cognition or anxiety regulation. Restoring adult neurogenesis in disrupted rats using oxytocin and conditionally suppressing the production of new neurons in socially naive GFAP–thymidine kinase rats showed that loss of 6-week-old neurons may be responsible for adaptive changes in social behavior.

“Lasting Adaptations in Social Behavior Produced by Social Disruption and Inhibition of Adult Neurogenesis” by Maya Opendak, Lily Offit, Patrick Monari, Timothy J. Schoenfeld, Anup N. Sonti, Heather A. Cameron, and Elizabeth Gould in Journal of Neuroscience. Published online June 29 2016 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4435-15.2016