Summary: Study links anhedonia, or the loss of pleasure, to the early onset of frontotemporal dementia. Neuroimaging revealed symptoms of anhedonia were marked by atrophy in the frontal and striatal brain areas of those with FTD.

Source: University of Sydney

People with early-onset dementia are often mistaken for having depression and now Australian research has discovered the cause: a profound loss of ability to experience pleasure – for example a delicious meal or beautiful sunset – related to degeneration of ‘hedonic hotspots’ in the brain where pleasure mechanisms are concentrated.

The University of Sydney-led research revealed marked degeneration, or atrophy, in frontal and striatal areas of the brain related to diminished reward-seeking, in patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

The researchers believe it is the first study to demonstrate profound anhedonia – the clinical definition for a loss of ability to experience pleasure – in people with FTD.

Anhedonia is also common in people with depression, bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder and can be particularly disabling for the individual.

In the study, patients with FTD – which generally affects people aged 40-65 – displayed a dramatic decline from pre-disease onset, in contrast to patients with Alzheimer’s disease, who were not found to show clinically significant anhedonia.

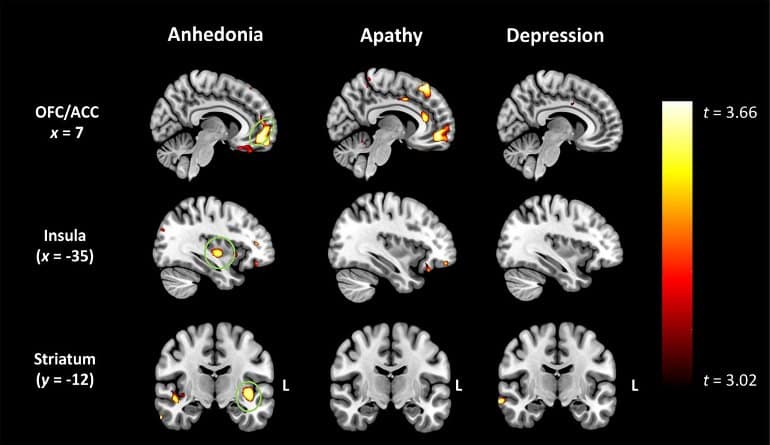

The results point to the importance of considering anhedonia as a primary presenting feature of FTD, where researchers found neural drivers in areas that are distinct from apathy or depression.

The findings were published today in the leading neuroscience journal, Brain.

The paper’s senior author, Professor Muireann Irish from the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre and School of Psychology in the Faculty of Science, said despite increasing evidence of motivational disturbances, no study had previously explored the capacity to experience pleasure in people with FTD.

“Much of human experience is motivated by the drive to experience pleasure but we often take this capacity for granted.

“But consider what it might be like to lose the capacity to enjoy the simple pleasures of life – this has stark implications for the wellbeing of people affected by these neurodegenerative disorders.

“Our findings also reflect the workings of a complex network of regions in the brain, signaling potential treatments,” said Professor Irish, who also recently published a paper in Brain about moral reasoning in FTD.

“Future studies will be essential to address the impact of anhedonia on everyday activities, and to inform the development of targeted interventions to improve quality of life in patients and their families.”

ABOUT THE STUDY:

This is the first study, to the researchers’ knowledge, to demonstrate profound anhedonia in FTD, reflecting loss of grey matter density in the frontal and striatal regions of the brain. Interestingly, anhedonia was not present in a group of participants with Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting this symptom is specific to FTD.

A total of 172 participants were recruited, including 87 FTD, 34 Alzheimer’s disease participants. Using brain imaging, researchers found that the loss of pleasure related to degeneration in a discrete set of regions in the so-called pleasure system of the brain.

The study led by the University of Sydney includes researchers with affiliations with the ARC Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders, the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and the Black Dog Institute.

DECLARATION: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

About this dementia research news

Source: University of Sydney

Contact: Vivienne Reiner – University of Sydney

Image: The image is credited to University of Sydney

Original Research: Open access.

“Uncovering the prevalence and neural substrates of anhedonia in frontotemporal dementia” by Muireann Irish et al. Brain

Abstract

Uncovering the prevalence and neural substrates of anhedonia in frontotemporal dementia

Much of human behaviour is motivated by the drive to experience pleasure. The capacity to envisage pleasurable outcomes and to engage in goal-directed behaviour to secure these outcomes depends upon the integrity of frontostriatal circuits in the brain. Anhedonia refers to the diminished ability to experience, and to pursue, pleasurable outcomes, and represents a prominent motivational disturbance in neuropsychiatric disorders. Despite increasing evidence of motivational disturbances in frontotemporal dementia (FTD), no study to date has explored the hedonic experience in these syndromes.

Here, we present the first study to document the prevalence and neural correlates of anhedonia in FTD in comparison with Alzheimer’s disease, and its potential overlap with related motivational symptoms including apathy and depression. A total of 172 participants were recruited, including 87 FTD, 34 Alzheimer’s disease, and 51 healthy older control participants.

Within the FTD group, 55 cases were diagnosed with clinically probable behavioural variant FTD, 24 presented with semantic dementia, and eight cases had progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA). Premorbid and current anhedonia was measured using the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale, while apathy was assessed using the Dimensional Apathy Scale, and depression was indexed via the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale.

Whole-brain voxel-based morphometry analysis was used to examine associations between grey matter atrophy and levels of anhedonia, apathy, and depression in patients. Relative to controls, behavioural variant FTD and semantic dementia, but not PNFA or Alzheimer’s disease, patients showed clinically significant anhedonia, representing a clear departure from pre-morbid levels. Voxel-based morphometry analyses revealed that anhedonia was associated with atrophy in an extended frontostriatal network including orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal, paracingulate and insular cortices, as well as the putamen.

Although correlated on the behavioural level, the neural correlates of anhedonia were largely dissociable from that of apathy, with only a small region of overlap detected in the right orbitofrontal cortices whilst no overlapping regions were found between anhedonia and depression.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to demonstrate profound anhedonia in FTD syndromes, reflecting atrophy of predominantly frontostriatal brain regions specialized for hedonic tone. Our findings point to the importance of considering anhedonia as a primary presenting feature of behavioural variant FTD and semantic dementia, with distinct neural drivers to that of apathy or depression.

Future studies will be essential to address the impact of anhedonia on everyday activities, and to inform the development of targeted interventions to improve quality of life in patients and their families.