The largest nationwide clinical trial to study high-dose resveratrol long-term in people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease found that a biomarker that declines when the disease progresses was stabilized in people who took the purified form of resveratrol.

Resveratrol is a naturally occurring compound found in foods such as red grapes, raspberries, dark chocolate and some red wines.

The results, published online today in Neurology, “are very interesting,” says the study’s principal investigator, R. Scott Turner, MD, PhD, director of the Memory Disorders Program at Georgetown University Medical Center. Turner, who treats patients at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, cautions that the findings cannot be used to recommend resveratrol. “This is a single, small study with findings that call for further research to interpret properly.”

The resveratrol clinical trial was a randomized, phase II, placebo-controlled, double blind study in patients with mild to moderate dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. An “investigational new drug” application was required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to test the pure synthetic (pharmaceutical-grade) resveratrol in the study. It is not available commercially in this form.

The study enrolled 119 participants. The highest dose of resveratrol tested was one gram by mouth twice daily — equivalent to the amount found in about 1,000 bottles of red wine.

John Bozza, 80, participated in the study. Five years ago, his wife, Diana, began noticing “something wasn’t quite right.” He was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, but only a year later, his condition progressed to mild Alzheimer’s.

Diana, whose twin sister died from the same disease, says there are multiple reasons she and John decided to participate in the resveratrol study, and they now know he was assigned to take the active drug.

“I definitely want the medical community to find a cure,” she says. “And of course I thought there’s always a chance that John could have been helped, and who knows, maybe he was.”

Patients, like John, who were treated with increasing doses of resveratrol over 12 months showed little or no change in amyloid-beta40 (Abeta40) levels in blood and cerebrospinal fluid. In contrast, those taking a placebo had a decrease in the levels of Abeta40 compared with their levels at the beginning of the study.

“A decrease in Abeta40 is seen as dementia worsens and Alzheimer’s disease progresses; still, we can’t conclude from this study that the effects of resveratrol treatment are beneficial,” Turner explains. “It does appear that resveratrol was able to penetrate the blood brain barrier, which is an important observation. Resveratrol was measured in both blood and cerebrospinal fluid.”

The researchers studied resveratrol because it activates proteins called sirtuins, the same proteins activated by caloric restriction. The biggest risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s is aging, and studies with animals found that most age-related diseases–including Alzheimer’s–can be prevented or delayed by long-term caloric restriction (consuming two-thirds the normal caloric intake).

Turner says the study also found that resveratrol was safe and well tolerated. The most common side effects experienced by participants were gastrointestinal-related, including nausea and diarrhea. Also, patients taking resveratrol experienced weight loss while those on placebo gained weight.

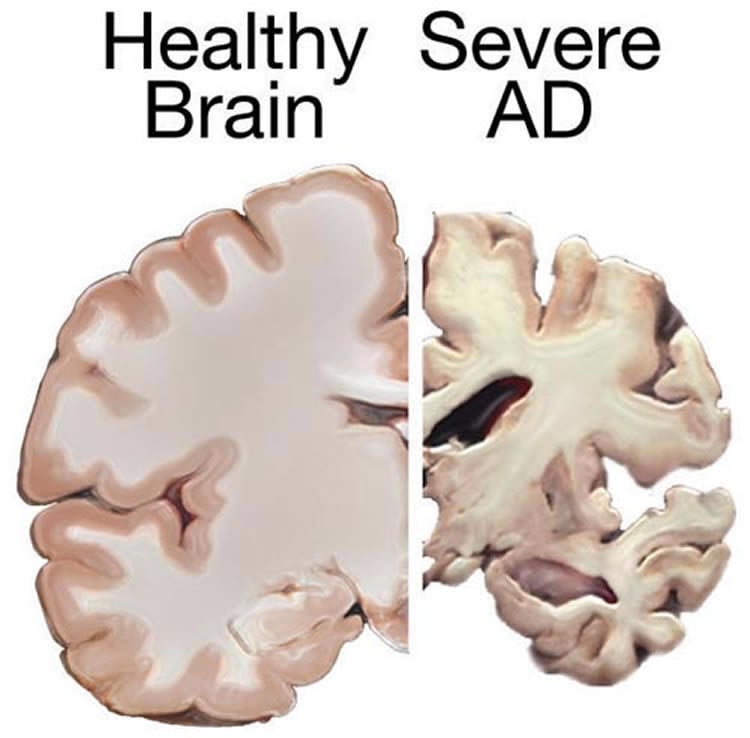

One outcome in particular was confounding, Turner notes. The researchers obtained brain MRI scans on participants before and after the study, and found that resveratrol-treated patients lost more brain volume than the placebo-treated group.

“We’re not sure how to interpret this finding. A similar decrease in brain volume was found with some anti-amyloid immunotherapy trials,” Turner adds. A working hypothesis is that the treatments may reduce inflammation (or brain swelling) found with Alzheimer’s.

The study, funded by the National Institute on Aging and conducted with the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study, began in 2012 and ended in 2014. GUMC was one of 21 participating medical centers across the U.S.

Further studies, including analysis of frozen blood and cerebrospinal fluid taken from patients, are underway to test possible drug mechanisms.

“Given safety and positive trends toward effectiveness in this phase 2 study, a larger phase 3 study is warranted to test whether resveratrol is effective for individuals with Alzheimer’s — or at risk for Alzheimer’s,” Turner says.

Resveratrol and similar compounds are being tested in many age-related disorders including cancer, diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders. The study Turner led, however, is the largest, longest and highest dose trial of resveratrol in humans to date.

Funding: The research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (U01 AG010483). Turner reports no personal financial interests related to the study.

Source: Karen Teber – Georgetown University Medical Center

Image Credit: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Abstract for “A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol for Alzheimer disease” by R. Scott Turner, Ronald G. Thomas, Suzanne Craft, Christopher H. van Dyck, Jacobo Mintzer, Brigid A. Reynolds, James B. Brewer, Robert A. Rissman, Rema Raman, Paul S. Aisen, and For the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study in Neurology. Published online September 11 2015 doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002035

Abstract

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol for Alzheimer disease

Objective: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter 52-week phase 2 trial of resveratrol in individuals with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease (AD) examined its safety and tolerability and effects on biomarker (plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42, CSF Aβ40, Aβ42, tau, and phospho-tau 181) and volumetric MRI outcomes (primary outcomes) and clinical outcomes (secondary outcomes).

Methods: Participants (n = 119) were randomized to placebo or resveratrol 500 mg orally once daily (with dose escalation by 500-mg increments every 13 weeks, ending with 1,000 mg twice daily). Brain MRI and CSF collection were performed at baseline and after completion of treatment. Detailed pharmacokinetics were performed on a subset (n = 15) at baseline and weeks 13, 26, 39, and 52.

Results: Resveratrol and its major metabolites were measurable in plasma and CSF. The most common adverse events were nausea, diarrhea, and weight loss. CSF Aβ40 and plasma Aβ40 levels declined more in the placebo group than the resveratrol-treated group, resulting in a significant difference at week 52. Brain volume loss was increased by resveratrol treatment compared to placebo.

Conclusions: Resveratrol was safe and well-tolerated. Resveratrol and its major metabolites penetrated the blood–brain barrier to have CNS effects. Further studies are required to interpret the biomarker changes associated with resveratrol treatment.

Classification of evidence: This study provides Class II evidence that for patients with AD resveratrol is safe, well-tolerated, and alters some AD biomarker trajectories. The study is rated Class II because more than 2 primary outcomes were designated.

“A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol for Alzheimer disease” by R. Scott Turner, Ronald G. Thomas, Suzanne Craft, Christopher H. van Dyck, Jacobo Mintzer, Brigid A. Reynolds, James B. Brewer, Robert A. Rissman, Rema Raman, Paul S. Aisen, and For the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study in Neurology. Published online September 11 2015 doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002035