Mice provide clues for alleviating treatment-resistant depression.

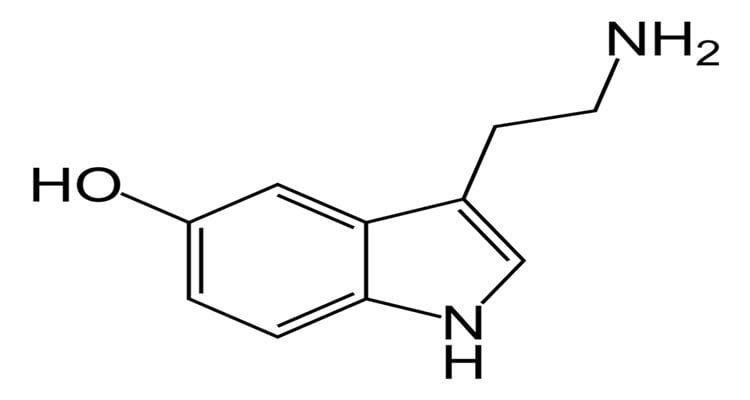

Mice genetically deficient in serotonin — a crucial brain chemical implicated in clinical depression — are more vulnerable than their normal littermates to social stressors, according to a Duke study appearing this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Following exposure to stress, the serotonin-deficient mice also did not respond to a standard antidepressant, fluoxetine (Prozac), which works by boosting serotonin transmission between neighboring neurons.

The new results may help explain why some people with depression seem unresponsive to treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the most common antidepressant drugs on the market today. The findings also point to several possible therapeutic strategies to explore for treatment-resistant depression.

“Our results are very exciting because they establish in a genetically defined animal model of serotonin deficiency, that low serotonin could be a contributing factor to the development of depression in response to psychosocial stress — and can lead to the failure of SSRIs to alleviate symptoms of depression,” said senior author Marc Caron, the James B. Duke professor of cell biology in the Duke University School of Medicine, and a member of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences.

The exact causes of depression are unclear. Although scientists have traditionally thought that low brain serotonin could cause depression, the idea is difficult to test directly and increasingly controversial. At the same time, researchers have gained a greater appreciation for the many environmental factors — especially stress — that can bring on or worsen depression.

In the new study, researchers used a transgenic mouse strain called Tph2KI that has only 20-40% of normal levels of serotonin in its brain. These mice harbor an extremely rare mutation that was first identified in a small group of people with major depression.

Caron’s group has been studying how the Tph2KI mice respond to different kinds of stress, showing previously that serotonin deficiency can affect susceptibility to some types of stress but not others, findings that may have implications for understanding how low levels of serotonin could contribute to mental illness.

In the new study, lead author Benjamin Sachs, a postdoctoral researcher in Caron’s group, tested the responses of these mice to a type of psychosocial stress: social defeat stress.

The team stressed out mice by housing them each with an aggressive stranger mouse briefly every day for 7-10 days. Later, the scientists examined whether the test mice would avoid interacting with an unfamiliar mouse — a depression-like behavior.

A week of social stress was not sufficient for normal mice to show signs of depression, but the serotonin-deficient mice did. Longer periods of stress exposure led to depression-like behavior in both groups.

The researchers then found that a 3-week treatment with Prozac following the stress exposure alleviated depression-like symptoms in normal mice, but not mutant mice.

Prozac and other SSRIs work by blocking the ability of cells to recapture serotonin, so it makes sense that the drugs would be less effective in animals with abnormally low levels of serotonin to begin with, Caron said.

A few case studies have suggested that targeting a brain area called the lateral habenula could help alleviate treatment-resistant depression. This area is known as a ‘punishment’ region of the brain because its neurons are active in the absence of reward. And scientists think that an overactive lateral habenula might trigger depression.

In the new study, the Caron group targeted the lateral habenula with a designer drug and receptor (called DREADDs for ‘designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs’) that allows them to control the activity of particular neurons in a living animal. Inhibiting lateral habenula neurons reversed the social avoidance behavior in the serotonin-deficient mice, they found.

Although DREADDs aren’t appropriate for use in humans, showing that the lateral habenula-targeted drugs can be used to alleviate depression-like behavior in animals is “an important first step,” Sachs said.

“The next step is to figure out how we can turn off this brain region in a relatively non-invasive way that would have better therapeutic potential,” Sachs added.

Another clue for potential new therapies came from biochemical comparisons of the brains of the mutant and normal mice. The researchers found that social stressors seemed to change where in the brain the signaling molecule β-catenin is being produced in normal mice, but not in the Tph2KI mice.

Taken with other evidence, these new findings suggest that serotonin deficiency may block a critical molecular pathway that includes β-catenin and that may be involved in resilience.

“If we can identify what’s both upstream and downstream of β-catenin we might be able to come up with attractive drug targets to activate this pathway and promote resilience,” Sachs said.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (MH79201, MH60451, F32-MH093092, MH79201-03S1), the Lennon Family Foundation, Duke University’s Trinity College of Arts and Sciences, and the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences.

Contact: Karl Bates – Duke

Source: Duke press release

Image Source: The image is credited to Harbinary and is in the public domain

Original Research: Abstract for “Brain 5-HT deficiency increases stress vulnerability and impairs antidepressant responses following psychosocial stress” by Benjamin D. Sachs, Jason R. Ni, and Marc G. Caron in PNAS. Published online February 9 2015 doi:10.1073/pnas.1416866112