Summary: After just one season of playing football, neuroimaging technology reveals changes in gray and white matter correlated with exposure to head trauma in high school students, a new study reports.

Source: RSNA.

Brain imaging exams performed on high school football players after just one season revealed changes in both the gray and white matter that correlated with exposure to head impacts, according to a new study that will be presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

“It’s important to understand the potential changes occurring in the brain related to youth contact sports,” said Elizabeth Moody Davenport, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas, who led this analysis. “We know that some professional football players suffer from a serious condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. We are attempting to find out when and how that process starts, so that we can keep sports a healthy activity for millions of children and adolescents.”

The study included 24 players from a high school football team in North Carolina, each of whom wore a helmet outfitted with the Head Impact Telemetry System (HITS) during all practices and games. The helmets are lined with six accelerometers, or sensors, that measure the magnitude, location and direction of a hit. Data from the helmets can be uploaded to a computer for analysis.

“We saw changes in these young players’ brains on both structural and functional imaging after a single season of football,” Dr. Davenport said.

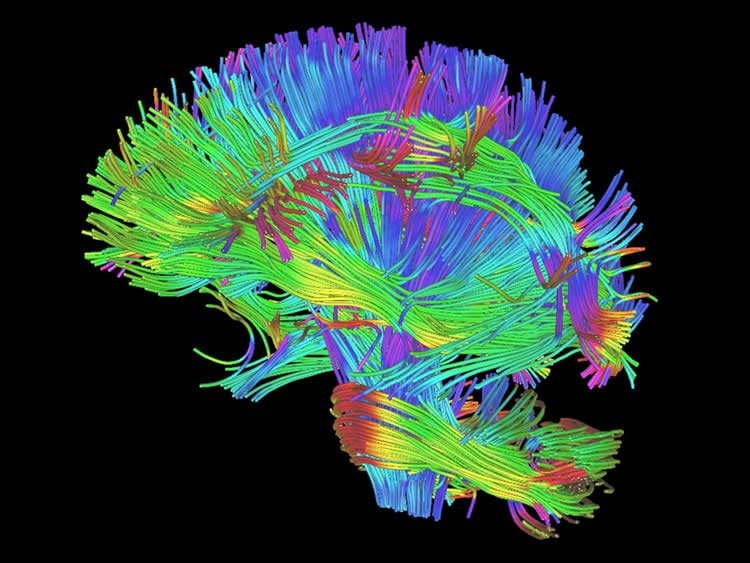

In the study, each player underwent pre- and post-season imaging: a specialized MRI scan, from which diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) data were extracted to measure the brain’s white matter integrity, and a magnetoencephalography (MEG) scan, which records and analyzes the magnetic fields produced by brain waves. Diffusion imaging can measure the structural white matter changes in the brain, and MEG assesses changes in function.

“MEG can be used to measure delta waves in the brain, which are a type of distress signal,” Dr. Davenport said. “Delta waves represent slow wave activity that increases after brain injuries. The delta waves we saw came from the surface of the brain, while diffusion imaging is a measure of the white matter deeper in the brain.”

The research team calculated the change in imaging metrics between the pre- and post-season imaging exams. They measured abnormalities observed on diffusion imaging and abnormally increased delta wave activity on MEG. The imaging results were then combined with player-specific impact data from the HITS. None of the 24 players were diagnosed with a concussion during the study.

Players with greater head impact exposure had the greatest change in diffusion imaging and MEG metrics.

“Change in diffusion imaging metrics correlated most to linear acceleration, similar to the impact of a car crash,” Dr. Davenport said. “MEG changes correlated most to rotational impact, similar to a boxer’s punch. These results demonstrate that you need both imaging metrics to assess impact exposure because they correlate with very different biomechanical processes.”

Dr. Davenport said similar studies are being conducted this fall, and a consortium has been formed to continue the brain imaging research in youth contact sports across the country.

“Without a larger population that is closely followed in a longitudinal study, it is difficult to know the long-term effects of these changes,” she said. “We don’t know if the brain’s developmental trajectory is altered, or if the off-season time allows for the brain to return to normal.”

Co-authors on the study are Jillian Urban, Ph.D., Ben Wagner, B.S., Mark A. Espeland, Ph.D., Christopher T. Whitlow, M.D., Ph.D., Joel Stitzel, Ph.D., and Joseph A. Maldjian, M.D.

Source: Linda Brooks – RSNA

Image Source: This NeuroscienceNews.com images are credited to RSNA.

Original Research: The study will be presented at RSNA 2016 – 102nd Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting in Chicago, November 27- December 2 2016.

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]RSNA. “Head Impacts Lead to Brain Changes in High School Football Players.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 28 November 2016.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/concussion-neurology-school-football-5614/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]RSNA. (2016, November 28). Head Impacts Lead to Brain Changes in High School Football Players. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved November 28, 2016 from https://neurosciencenews.com/concussion-neurology-school-football-5614/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]RSNA. “Head Impacts Lead to Brain Changes in High School Football Players.” https://neurosciencenews.com/concussion-neurology-school-football-5614/ (accessed November 28, 2016).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]