Summary: Researchers report people retain arbitrary associations when they learned the associations in short sessions spaced over a few weeks rather than one 20 minute session.

Source: SfN.

Associations between neutral stimuli and monetary rewards are strengthened over the course of weeks of learning, according to a human study published in Journal of Neuroscience that investigated learning over an extended period of time. The research may have implications for the study of addiction, in which learned associations between drug and reward are acquired gradually.

Studies of reward-based learning in humans typically involve minutes-long training sessions. These experiments contrast with most animal research that involves learning over days or weeks, limiting the translation of this research to humans. In addition, rapid learning tasks are not representative of how people actually develop their preferences over time.

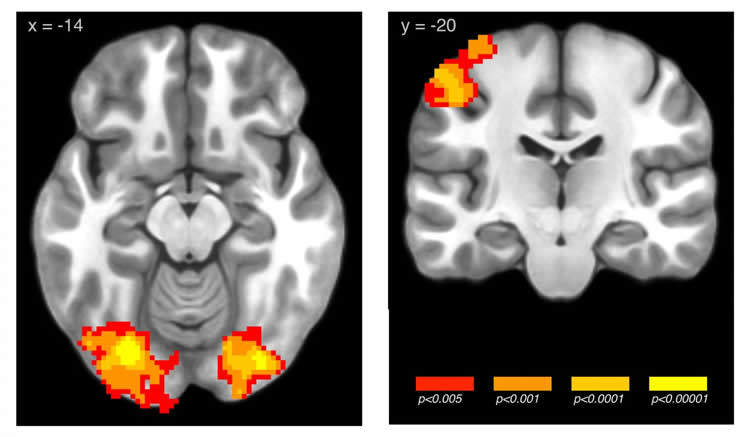

Elliott Wimmer and colleagues found that men and women better retained arbitrary associations between pictures of landscapes and monetary gain when they learned the associations in short sessions spaced out over weeks compared to a single, 20-minute session. The researchers’ neuroimaging data reveal that training led to greater engagement of learning-related regions of the brain. each type of learning engaged different parts of the brain. These results provide a starting point for exploring how learned associations that have negative effects on human health and wellbeing, as in addition, could be unlearned.

Funding: NIH/National Institute on Aging, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Stanford Center for Cognitive and Neurobiological Imaging funded this study.

Source: David Barnstone – SfN

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Wimmer et al., JNeurosci (2018).

Original Research: Abstract for “Reward learning over weeks versus minutes increases the neural representation of value in the human brain” by G. Elliott Wimmer, Jamie K. Li, Krzysztof J. Gorgolewski and Russell A. Poldrack in Journal of Neuroscience. Published July 30 2018.

doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0075-18.2018

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]SfN”How Time Affects Learning.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 30 July 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/time-learning-9631/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]SfN(2018, July 30). How Time Affects Learning. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved July 30, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/time-learning-9631/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]SfN”How Time Affects Learning.” https://neurosciencenews.com/time-learning-9631/ (accessed July 30, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Reward learning over weeks versus minutes increases the neural representation of value in the human brain

Over the past few decades, neuroscience research has illuminated the neural mechanisms supporting learning from reward feedback. Learning paradigms are increasingly being extended to study mood and psychiatric disorders as well as addiction. However, one potentially critical characteristic that this research ignores is the effect of time on learning: human feedback learning paradigms are usually conducted in a single rapidly paced session, while learning experiences in ecologically relevant circumstances and in animal research are almost always separated by longer periods of time. In our experiments, we examined reward learning in short condensed sessions distributed across weeks vs. learning completed in a single “massed” session in male and female participants. As expected, we found that after equal amounts of training, accuracy was matched between the spaced and massed conditions. However, in a 3-week follow-up, we found that participants exhibited significantly greater memory for the value of spaced-trained stimuli. Supporting a role for short-term memory in massed learning, we found a significant positive correlation between initial learning and working memory capacity. Neurally, we found that patterns of activity in the medial temporal lobe and prefrontal cortex showed stronger discrimination of spaced- vs. massed-trained reward values. Further, patterns in the striatum discriminated between spaced- and massed-trained stimuli overall. Our results indicate that single-session learning tasks engage partially distinct learning mechanisms from spaced sessions of training. Our studies begin to address a large gap in our knowledge of human learning from reinforcement, with potential implications for our understanding of mood disorders and addiction.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

Humans and animals learn to associate predictive value with stimuli and actions, and these values then guide future behavior. Such reinforcement-based learning often happens over long time periods, in contrast to most studies of reward-based learning in humans. In experiments that tested the effect of spacing on learning, we found that associations learned in a single massed session were correlated with short-term memory and significantly decayed over time, while associations learned in short massed sessions over weeks were well-maintained. Additionally, patterns of activity in the medial temporal lobe and prefrontal cortex discriminated the values of stimuli learned over weeks but not minutes. These results highlight the importance of studying learning over time, with potential applications to drug addiction and psychiatry.