Summary: Social isolation has been directly linked to structural changes in brain areas associated with memory and cognitive function. Researchers report socially isolated people are 26% more likely to develop dementia later in life.

Source: University of Warwick

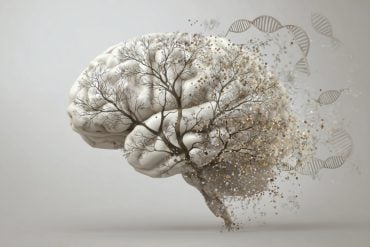

Social isolation is directly linked with changes in the brain structures associated with memory, making it a clear risk factor for dementia, scientists have found.

Setting out to investigate how social isolation and loneliness were related to later dementia, researchers at the University of Warwick, University of Cambridge and Fudan University used neuroimaging data from more than 30,000 participants in the UK Biobank data set. Socially isolated individuals were found to have lower gray matter volumes of brain regions involved in memory and learning.

The results of the study are published online in Neurology.

Based on data from the UK Biobank, an extremely large longitudinal cohort, the researchers used modelling techniques to investigate the relative associations of social isolation and loneliness with incident all-cause dementia.

After adjusting for various risk factors (including socio-economic factors, chronic illness, lifestyle, depression and APOE genotype), socially isolated individuals were shown to have a 26% increased likelihood of developing dementia.

Loneliness was also associated with later dementia, but that association was not significant after adjusting for depression, which explained 75% of the relationship between loneliness and dementia. Therefore, relative to the subjective feeling of loneliness, objective social isolation is an independent risk factor for later dementia. Further subgroup analysis showed that the effect was prominent in those over 60 years old.

Professor Edmund Rolls, neuroscientist from the University of Warwick Department of Computer Science, said: “There is a difference between social isolation, which is an objective state of low social connections, and loneliness, which is subjectively perceived social isolation.

“Both have risks to health but, using the extensive multi-modal data set from the UK Biobank, and working in a multidisciplinary way linking computational sciences and neuroscience, we have been able to show that it is social isolation, rather than the feeling of loneliness, which is an independent risk factor for later dementia. This means it can be used as a predictor or biomarker for dementia in the UK.

“With the growing prevalence of social isolation and loneliness over the past decades, this has been a serious yet underappreciated public health problem. Now, in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic there are implications for social relationship interventions and care – particularly in the older population.”

Professor Jianfeng Feng, from the University of Warwick Department of Computer Science, said: “We highlight the importance of an environmental method of reducing risk of dementia in older adults through ensuring that they are not socially isolated. During any future pandemic lockdowns, it is important that individuals, especially older adults, do not experience social isolation.”

Professor Barbara J Sahakian, of the University of Cambridge Department of Psychiatry, said: “Now that we know the risk to brain health and dementia of social isolation, it is important that the government and communities take action to ensure that older individuals have communication and interactions with others on a regular basis.”

About this social isolation and dementia research news

Author: Sheila Kiggins

Source: University of Warwick

Contact: Sheila Kiggins – University of Warwick

Image: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Closed access.

“Associations of Social Isolation and Loneliness With Later Dementia” by Edmund Rolls et al. Neurology

Abstract

Associations of Social Isolation and Loneliness With Later Dementia

Objective

To investigate the independent associations of social isolation and loneliness with incident dementia and to explore the potential neurobiological mechanisms.

Methods

We utilized the UK Biobank cohort to establish Cox proportional hazard models with social isolation and loneliness as separate exposures. Demographic (sex, age and ethnicity), socioeconomic (education level, household income and Townsend deprivation index), biological (BMI, APOE genotype, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease and other disabilities), cognitive (speed of processing and visual memory), behavioral (current smoker, alcohol intake and physical activity), and psychological (social isolation or loneliness, depressive symptoms and neuroticism) factors measured at baseline were adjusted. Then, voxel-wise brain-wide association analyses were used to identify gray matter volumes (GMV) associated with social isolation and with loneliness. Partial least squares regression was performed to test the spatial correlation of GMV differences and gene expression using the Allen Human Brain Atlas.

Results

We included 462,619 participants (mean age at baseline 57.0 years [SD 8.1]). With a mean follow-up of 11.7 years (SD 1.7), 4,998 developed all-cause dementia. Social isolation was associated with a 1.26-fold increased risk of dementia (95% CI, 1.15-1.37) independently of various risk factors including loneliness and depression (i.e., full adjustment). However, the fully adjusted hazard ratio for dementia related to loneliness was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.94-1.16); and 75% of this relationship was attributable to depressive symptoms. Structural MRI data were obtained from 32,263 participants (mean age 63.5 years [SD 7.5]). Socially isolated individuals had lower GMVs in temporal, frontal and other (e.g., hippocampal) regions. Mediation analysis showed that the identified GMVs partly mediated the association between social isolation at baseline and cognitive function at follow-up. Social isolation-related lower GMVs were related to under-expression of genes that are down-regulated in Alzheimer’s disease and to genes that are involved in mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative phosphorylation.

Conclusion

Social isolation is a risk factor for dementia that is independent of loneliness and many other covariates. Social isolation-related brain structural differences coupled with different molecular functions also support the associations of social isolation with cognition and dementia. Social isolation may thus be an early indicator of an increased risk of dementia.