Summary: Sounds presented during sleep associated with previously learned stimuli reactivated memory and improved memory storage.

Source: Northwestern University

A new study looks deep inside the brain, where previous learning was reactivated during sleep, resulting in improved memory.

Neuroscientists from Northwestern University teamed up with clinicians from the University of Chicago Epilepsy Center to study the brain electrical activity in five of the center’s patients in response to sounds administered by the research team as part of a learning exercise.

The five patients who volunteered to participate in the study had electrode probes implanted into the brain for the purpose of investigating potential treatments for their seizure disorders.

While prior studies have used EEG recordings captured by electrodes on the head to measure memory processing during sleep, this is the first study to record such electrical activity from inside the brain.

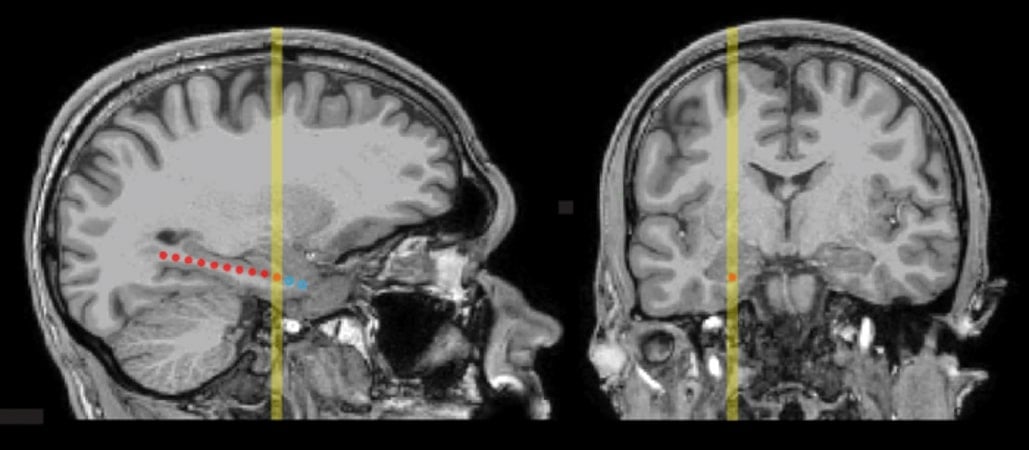

The study found participants significantly improved their performance in a recall test the next morning. The mapped brain activity allowed the researchers to take a big step forward in understanding how memory storage works by providing visual data identifying the areas of the brain engaged in the process of overnight memory storage.

Although the number of patients studied was necessarily small, strong conclusions were possible because all five patients showed the same patterns of memory improvement and electrical activity.

“We are investigating how people manage to remember the things they’ve learned, rather than forgetting them,” said Ken Paller, director of the Cognitive Neuroscience Program at Northwestern and senior researcher on the study. “Our view is that sleep contributes to that ability.”

Paller is a professor of psychology and the James Padilla Chair in Arts and Science at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences.

Study collaborators include neurology and neurological surgery researchers at the University of Chicago, and psychology researchers at Northwestern, the University of Michigan, and Middlebury College (Vermont).

How the study was done

One night, while each patient slept in a hospital room, the team recorded electrophysiological responses to 10-20 sounds that were repeatedly presented. All the sounds were played very quietly so as to avoid arousal. Half of the sounds were associated with objects and their precise spatial locations that patients learned before sleep using a laptop computer, such as the jingling sound of car keys, to help recall their location.

After sleep, the researchers found systematic improvements in spatial recall, replicating results from prior studies using EEG recordings from the scalp. Patients more accurately indicated the remembered locations on the laptop screen.

The new data from the implanted brain electrodes showed that object sounds presented during sleep elicited increased oscillatory activity, including increases in theta, sigma, and gamma EEG bands.

The presence of electrophysiological activity in the hippocampus and the adjacent medial temporal area of the cerebral cortex, when the sounds were presented during sleep, reflected the reactivation and strengthening of corresponding spatial memories.

Gamma responses were consistently associated with the degree of improvement in spatial memory exhibited after sleep. This electrophysiological evidence led the researchers to conclude that sleep-based enhancement of memory storage takes place in these brain regions.

“The orthodox assumption used to be that such sounds would be blocked out when people are sleeping,” Paller said. “Instead, these sounds allowed us to demonstrate that brain structures such as the hippocampus are responsive when memories are reactivated, helping us to retain the knowledge we gain when we’re awake.

“At times, remembering and forgetting seems random. We can remember irrelevant details while forgetting what we most want to remember. The new answer to this long-standing mystery, highlighted by this research, is that memories are revisited when we sleep, even though we wake up not knowing it happened,” Paller said.

About this sleep and memory research news

Author: Stephanie Kulke

Source: Northwestern University

Contact: Stephanie Kulke – Northwestern University

Image: The image is credited to Department of Neurological Surgery, The University of Chicago

Original Research: Closed access.

“Electrophysiological markers of memory consolidation in the human brain when memories are reactivated during sleep” by Ken Paller et al. PNAS

Abstract

Electrophysiological markers of memory consolidation in the human brain when memories are reactivated during sleep

Human accomplishments depend on learning, and effective learning depends on consolidation. Consolidation is the process whereby new memories are gradually stored in an enduring way in the brain so that they can be available when needed.

For factual or event knowledge, consolidation is thought to progress during sleep as well as during waking states and to be mediated by interactions between hippocampal and neocortical networks. However, consolidation is difficult to observe directly but rather is inferred through behavioral observations.

Here, we investigated overnight memory change by measuring electrical activity in and near the hippocampus.

Electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings were made in five patients from electrodes implanted to determine whether a surgical treatment could relieve their seizure disorders.

One night, while each patient slept in a hospital monitoring room, we recorded electrophysiological responses to 10 to 20 specific sounds that were presented very quietly, to avoid arousal. Half of the sounds had been associated with objects and their precise spatial locations that patients learned before sleep.

After sleep, we found systematic improvements in spatial recall, replicating prior results. We assume that when the sounds were presented during sleep, they reactivated and strengthened corresponding spatial memories.

Notably, the sounds also elicited oscillatory intracranial EEG activity, including increases in theta, sigma, and gamma EEG bands. Gamma responses, in particular, were consistently associated with the degree of improvement in spatial memory exhibited after sleep.

We thus conclude that this electrophysiological activity in the hippocampus and adjacent medial temporal cortex reflects sleep-based enhancement of memory storage.