Max Planck researchers discover the anatomic reasons for the persistence of musical memory in Alzheimer patients.

In comparison to other memory functions, long-term musical memory in Alzheimer patients often remains intact and functional for a surprisingly long time. However, until now, the underlying causes of this phenomenon have remained in the dark. In a recent study, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, the University of Amsterdam and INSERM Caen have pinpointed the location of musical memory for the first time and shown that this area of the brain remains largely intact despite progressive degeneration of the brain in Alzheimer patients.

Surprisingly, Alzheimer’s often spares long-term musical memory. In practice, carers and therapists take advantage of this phenomenon to stimulate their patients with music. It is often possible for music to reactivate memories, emotions and impressions. In some cases, patients are able to sing lyrics of songs even when speaking has become almost impossible for them.

However, this phenomenon has remained scientifically unexplained. “This is the first neuroscientific study to provide an anatomic explanation for the persistence of musical memory,” says Jörn-Henrik Jacobsen, scientist at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig and the University of Amsterdam.

To shed light on the matter, the researchers first located the seat of long-term musical memory in the brain with the help of functional ultra-high-field magnetic resonance imaging. For this purpose, they ran a behavioural experiment using a set of song stimuli taken from the top 10 pop hit charts in Germany between 1977 and 2007, children’s songs, oldies and well-known classical pieces. The aim was to identify melodies that the study participants were familiar with. “An individual’s musical experience and musical memories are largely shaped by social and cultural circumstances. It was therefore important to avoid a subjective choice of songs and to have a group selection instead,” Jacobsen explains. The chosen musical excerpts were combined with totally unknown but characteristically similar pieces of music in groups of three.

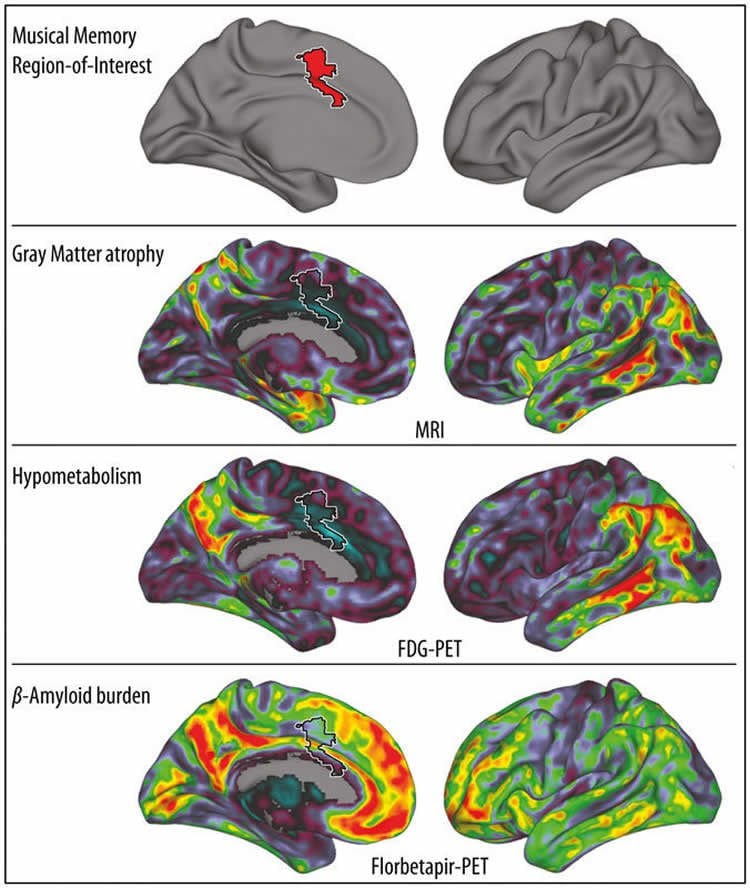

While being monitored by MRI, the subjects listened to groups of three musical samples consisting of a long-known song, a song they had just heard and a completely unknown melody. The data were then analyzed with the help of statistical pattern-recognition methods. The scientists were able to conclude from the various active brain areas which of the three categories (long-known, recently heard, unknown) the study participants had just heard. They identified a region in the supplementary motor cerebral cortex that is responsible for long-term musical memory – an area that is involved in movement. “Our study shows that the temporal lobes are not essential for musical memory, as had previously been suspected, but rather areas associated with complex motor functions,” Jacobsen explains.

In a second step, the scientists compared the areas responsible for musical memory in the healthy group with anatomic findings from a study with Alzheimer patients. In the process, they considered three important features of the disease: loss of neurons, reduced metabolism and deposition of amyloid protein in the affected brain areas.

They found that the brain area that had been identified as the seat of long-term musical memory does in fact lose fewer neurons than the rest of the brain. Also, metabolism in this area does not decline as much. The extent of amyloid deposits is similar to that in other areas of the brain but does not lead to the deficits otherwise associated with advanced stages of the disease. The brain areas responsible for long-term musical memory are therefore often affected least by neuron loss and typical metabolic disorders in Alzheimer patients.

The results of the study indicate that long-term musical memory is better preserved in Alzheimer patients than short-term memory, autobiographical long-term memory and speech. It can therefore remain largely intact even in advanced stages of the disease. “Our findings also lend support to a theory previously proposed in connection with other studies that found stronger network connections between the anterior gyrus cinguli and other nodes in Alzheimer patients. This suggests that this area of the brain also provides specific compensatory functions as the disease progresses,” Jacobsen says, in explanation of the results’ importance.

The scientists hope their investigations will give fresh impetus to research into the poorly understood mechanisms of long-term musical memory in Alzheimer patients. “In future, a sound understanding of the complex relationships could lead to a real therapeutic benefit of music in patient care,” Jacobsen believes.

Source: Katja Paasche – Max Planck Institute

Image Credit: Image credited to MPI f. Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences

Original Research: Abstract for “Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease” by Jörn-Henrik Jacobsen, Johannes Stelzer, Thomas Hans Fritz, Gael Chételat, Renaud La Joie, and Robert Turner in Brain. Published online June 3 2015 doi:10.1093/brain/awv135

Abstract

Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease

Musical memory is considered to be partly independent from other memory systems. In Alzheimer’s disease and different types of dementia, musical memory is surprisingly robust, and likewise for brain lesions affecting other kinds of memory. However, the mechanisms and neural substrates of musical memory remain poorly understood. In a group of 32 normal young human subjects (16 male and 16 female, mean age of 28.0 ± 2.2 years), we performed a 7 T functional magnetic resonance imaging study of brain responses to music excerpts that were unknown, recently known (heard an hour before scanning), and long-known. We used multivariate pattern classification to identify brain regions that encode long-term musical memory. The results showed a crucial role for the caudal anterior cingulate and the ventral pre-supplementary motor area in the neural encoding of long-known as compared with recently known and unknown music. In the second part of the study, we analysed data of three essential Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in a region of interest derived from our musical memory findings (caudal anterior cingulate cortex and ventral pre-supplementary motor area) in 20 patients with Alzheimer’s disease (10 male and 10 female, mean age of 68.9 ± 9.0 years) and 34 healthy control subjects (14 male and 20 female, mean age of 68.1 ± 7.2 years). Interestingly, the regions identified to encode musical memory corresponded to areas that showed substantially minimal cortical atrophy (as measured with magnetic resonance imaging), and minimal disruption of glucose-metabolism (as measured with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography), as compared to the rest of the brain. However, amyloid-β deposition (as measured with 18F-flobetapir positron emission tomography) within the currently observed regions of interest was not substantially less than in the rest of the brain, which suggests that the regions of interest were still in a very early stage of the expected course of biomarker development in these regions (amyloid accumulation → hypometabolism → cortical atrophy) and therefore relatively well preserved. Given the observed overlap of musical memory regions with areas that are relatively spared in Alzheimer’s disease, the current findings may thus explain the surprising preservation of musical memory in this neurodegenerative disease.

“Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease” by Jörn-Henrik Jacobsen, Johannes Stelzer, Thomas Hans Fritz, Gael Chételat, Renaud La Joie, and Robert Turner in Brain. Published online June 3 2015 doi:10.1093/brain/awv135