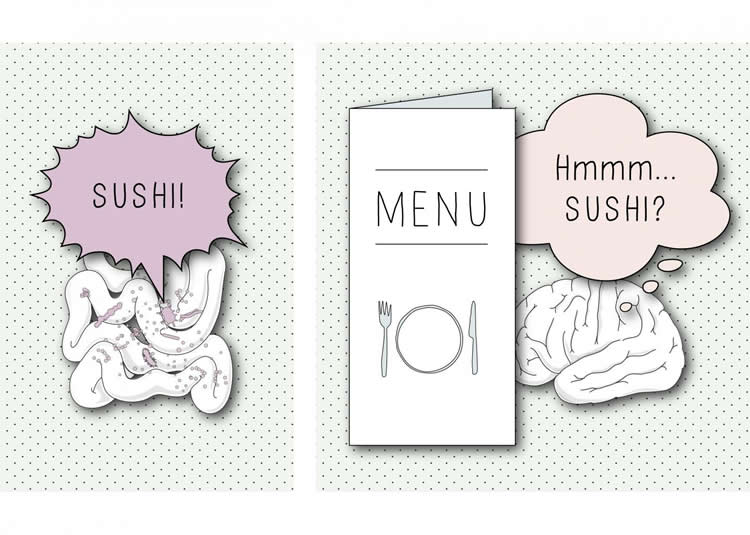

Summary: Researchers report gut bacteria influence the brain when it comes to deciding on foods to eat.

Source: PLOS.

Neuroscientists have, for the first time, shown that gut bacteria “speak” to the brain to control food choices in animals. In a study publishing April 25 in the Open Access journal PLOS Biology, researchers identified two species of bacteria that have an impact on animal dietary decisions. The investigation was led by Carlos Ribeiro, and colleagues from the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown in Lisbon, Portugal and Monash University, Australia.

There’s no question that nutrients and the microbiome, the community of bacteria that resides in the gut, impact health. For instance, diseases like obesity have been associated with the composition of the diet and the microbiome.

However, the notion that microbes might also be able to control behavior seems a big conceptual leap. Yet that’s what the new study shows.

Experiments conducted using the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, a model organism allowed the scientists to dissect the complex interaction of diet and microbes and its effect on food preference. The scientists initially showed that flies deprived of amino acids showed decreased fertility and increased preference for protein-rich food. Indeed, the team found that the removal of any single essential amino acid was sufficient to increase the flies’ appetite for protein-rich food.

Furthermore, the scientists tested the impact on food choices of five different species of bacteria that are naturally present in the guts of fruit flies in the wild. The results exceeded the scientists’ expectations: two specific bacterial species could abolish the increased appetite for protein in flies that were fed food lacking essential amino acids. “With the right microbiome, fruit flies are able to face these unfavorable nutritional situations,” says Santos.

“In the fruit fly, there are five main bacterial species; in humans there are hundreds,” adds co-author Patrícia Francisco. This highlights the importance of using simple animal models to gain insights into factors that may be crucial for human health.

How could the bacteria act on the brain to alter appetite? “Our first hypothesis was that these bacteria might be providing the flies with the missing essential amino acids,” Santos explains. However, the experiments did not support this hypothesis.

Instead, the gut bacteria “seem to induce some metabolic change that acts directly on the brain and the body, which mimics a state of protein satiety,” Santos says.

In sum, this study shows not only that gut bacteria act on the brain to alter what animals want to eat, but also that they might do so by using a new, unknown mechanism.

Funding: Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) (grant number postdoctoral fellowship SFRH/BPD/78947/2011). Received by RLG. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) (grant number PTDC/BIA-BCM/118684/2010). Received by CR. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Human Frontier Science Program (grant number RGP0022/2012). Received by CR. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; EUROPEAN COMMISSION – MARIE CURIE ACTIONS (grant number FLiACT – Grant agreement no.: 289941). Received by CR. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Ciência sem Fronteiras program of the CNPq (grant number 200207/2012-1). Received by GTF. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Royal Society (grant number UF100158). Received by MDWP. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; BIAL Foundation (grant number 283/14). Received by CR. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; EMBO (grant number ALTF 1602-2011). Received by RLG. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant number BB/I011544/1). Received by MDWP. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Champalimaud Foundation. Received by CR. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Australian Research Council (grant number Australian Research Council Future Fellow – FT150100237). Received by MDWP. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) (grant number postdoctoral fellowship SFRH/BPD/76201/2011). Received by ZCS. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) (grant number postdoctoral fellowship SFRH/BPD/79325/2011 ). Received by PMI. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Kavli Foundation. Received by CR. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests: I have read the journal’s policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests. PMI has a commercial interest in the flyPAD open-source technology.

Source: Carlos Ribeiro – PLOS

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Gil Costa.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Commensal bacteria and essential amino acids control food choice behavior and reproduction” by Ricardo Leitão-Gonçalves, Zita Carvalho-Santos, Ana Patrícia Francisco, Gabriela Tondolo Fioreze, Margarida Anjos, Célia Baltazar, Ana Paula Elias, Pavel M. Itskov, Matthew D. W. Piper, and Carlos Ribeiro in PLOS Biology. Published online April 25 2017 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2000862

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]PLOS “Gut Bacteria Tells the Brain What Animals Should Eat.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 25 April 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/microbiome-gut-food-6505/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]PLOS (2017, April 25). Gut Bacteria Tells the Brain What Animals Should Eat. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved April 25, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/microbiome-gut-food-6505/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]PLOS “Gut Bacteria Tells the Brain What Animals Should Eat.” https://neurosciencenews.com/microbiome-gut-food-6505/ (accessed April 25, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Commensal bacteria and essential amino acids control food choice behavior and reproduction

Choosing the right nutrients to consume is essential to health and wellbeing across species. However, the factors that influence these decisions are poorly understood. This is particularly true for dietary proteins, which are important determinants of lifespan and reproduction. We show that in Drosophila melanogaster, essential amino acids (eAAs) and the concerted action of the commensal bacteria Acetobacter pomorum and Lactobacilli are critical modulators of food choice. Using a chemically defined diet, we show that the absence of any single eAA from the diet is sufficient to elicit specific appetites for amino acid (AA)-rich food. Furthermore, commensal bacteria buffer the animal from the lack of dietary eAAs: both increased yeast appetite and decreased reproduction induced by eAA deprivation are rescued by the presence of commensals. Surprisingly, these effects do not seem to be due to changes in AA titers, suggesting that gut bacteria act through a different mechanism to change behavior and reproduction. Thus, eAAs and commensal bacteria are potent modulators of feeding decisions and reproductive output. This demonstrates how the interaction of specific nutrients with the microbiome can shape behavioral decisions and life history traits.

“Commensal bacteria and essential amino acids control food choice behavior and reproduction” by Ricardo Leitão-Gonçalves, Zita Carvalho-Santos, Ana Patrícia Francisco, Gabriela Tondolo Fioreze, Margarida Anjos, Célia Baltazar, Ana Paula Elias, Pavel M. Itskov, Matthew D. W. Piper, and Carlos Ribeiro in PLOS Biology. Published online April 25 2017 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2000862