Summary: The between-sex performance gap when it comes to running is much narrower at shorter sprint distances, a new study reveals.

Source: Southern Methodist University

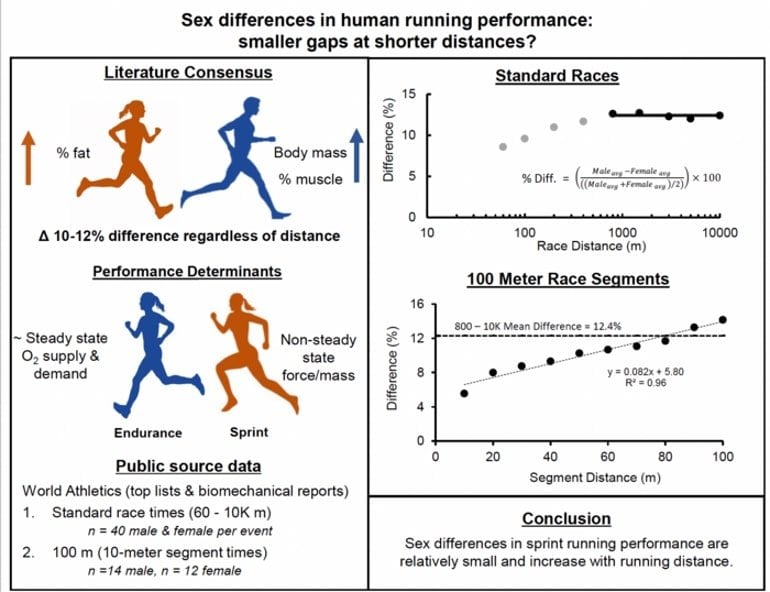

Conventional wisdom holds that men run 10-12 percent faster than women regardless of the distance raced. But new research suggests that the between-sex performance gap is much narrower at shorter sprint distances.

It has long been established that men outpace women by relatively large margins in mid- and longer-distance events. But speed over short distances is determined by different factors – specifically, the magnitude of the ground forces athletes can apply in relation to their body mass. Women tend to be smaller than men and, all things being equal, muscular force to body mass ratios are greater in smaller individuals.

Ph.D. candidate Emily McClelland, working with Peter Weyand, the Director of SMU’s Locomotor Performance Lab, quantified sex performance differences using data from sanctioned international athletic competitions such as the Olympics and World Championships.

They hypothesized that these data would reveal smaller male-female performance differences at shorter distances.

An accomplished athlete and former assistant director of strength and conditioning at Bowling Green State University, McClelland has always had a natural interest in the scientific basis of human performance.

More broadly, the understanding of comparative strength, speed and endurance capabilities of male and female athletes has been a highly challenging issue for modern sport. Yet, prior to the new SMU study, quantitative understanding of sex performance differences for short sprint events had received little attention.

McClelland’s background, male-female differences in force/mass capabilities, and existing data trends led her to hypothesize that sex differences in sprint running performance might be relatively small and increase with distance.

Her analysis of race data from sanctioned international competitions between 2003 and 2018 supported her initial hypothesis.

These data revealed that the difference between male and female performance time increased with event distance from 8.6 percent to 11 percent from shortest to longest sprint events (60 to 400 meters).

Additionally, within-race analysis of each 10-meter segment of the 100-meter event revealed a more pronounced pattern across distance – sex differences increased from a low of 5.6 percent for the first segment to a high of 14.2 percent in the last segment.

Why then are women potentially less disadvantaged versus men at shorter sprint distances?

In contrast to other running species like horses and dogs, there is significant variation in body size between human males and females. If all other factors are held equal, body size differences result in muscular force to body mass ratios that are greater in relatively smaller individuals.

Since sprinting velocities are directly dependent on the mass-specific forces runners can apply during the foot-to-ground contact phase of the stride, greater force/mass ratios of smaller individuals provide a theoretical relative advantage.

Additionally, the shorter legs of a female runner may confer the advantage of more steps and pushing cycles per unit time during the acceleration phase of a race.

These factors offset the advantages of males (longer legs and greater muscularity) that become more influential over longer distances.

Consider the example of Shelly-Ann Fraser Pryce, a Jamaican track and field star who is 5’0” tall, 115 pounds, and who holds two Olympic and five World Championship gold medals in her signature 100-meter event.

Her time at the 40-yard mark of a 100-meter race has been estimated to be as brief as 4.51 seconds—a time faster than nearly half of all the wide receivers and running backs that tested in the National Football League’s Scouting Combine in 2022.

In contrast to Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, most of these aspiring NFL football players are over 6’ tall and 200 pounds.

About this neuroscience and locomotion research news

Author: Monifa Thomas-Nguyen

Source: Southern Methodist University

Contact: Monifa Thomas-Nguyen – Southern Methodist University

Image: The image is credited to Journal of Applied Physiology

Original Research: Open access.

“Sex differences in human running performance: smaller gaps at shorter distances?” by Emily McClelland et al. Journal of Applied Physiology

Abstract

Sex differences in human running performance: smaller gaps at shorter distances?

Human, but not canine or equine running performance, is significantly stratified by sex. The degree of stratification has obvious implications for classification and regulation in athletics.

However, whether the widely cited sex difference of 10-12% applies equally to sprint and endurance running events is unknown.

Here, different determining factors for sprint (ground force/body mass) vs. endurance performance (energy supply & demand) and existing trends, led us to hypothesize that sex performance differences for sprint running would increase with distance and be relatively small.

We quantified sex performance differences using: 1) the race times of the world’s fastest males and females (n=40 each) over a 15-year period (2003-2018) at nine standard racing distances (60-10,000m), and 2) the 10-meter segment times of male (n=14) and female (n=12) athletes in World Championship 100-meter finals.

Between-sex performance time differences increased with sprint event distance [60m-8.6%, 100m-9.6%, 200m-11.0%, 400m-11.7%] and were smaller than the relatively-constant mean (12.4±0.3%) observed across the five longer events from 800-10,000 meters.

Between-sex time differences for the 10-meter segments within the 100-meter dash event, increased throughout spanning 5.6% to 14.2% from the first to last segment. We conclude that sex differences in sprint running performance increase with race and running distance.