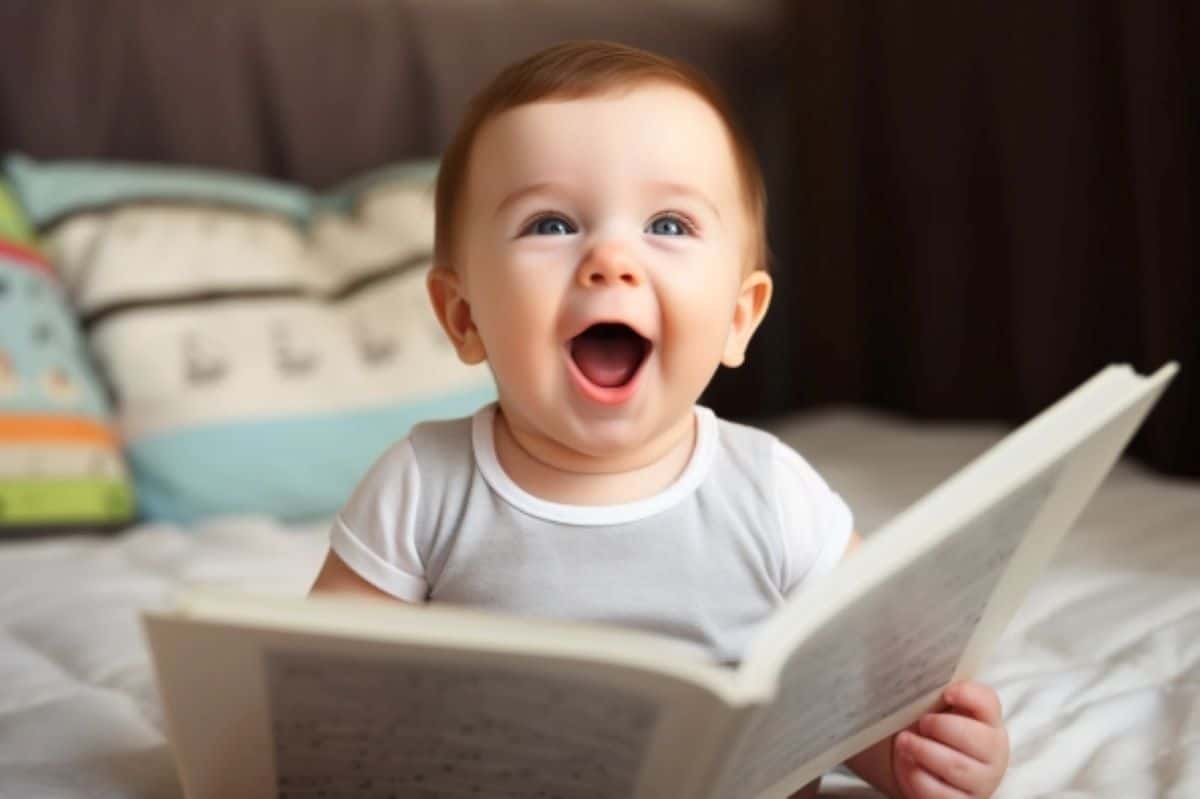

Summary: New research suggests that parents should use sing-song speech, such as nursery rhymes, with their babies, as it aids language development.

Contrary to the belief that phonetic information is the foundation of language, this study reveals that rhythmic speech plays a crucial role in language acquisition during a child’s first months. Phonetic information is not reliably processed until around seven months of age, whereas rhythmic information helps babies recognize word boundaries from the start.

The study sheds light on language learning and its relation to dyslexia and developmental language disorders.

Key Facts:

- Babies learn language more effectively through rhythmic speech, emphasizing word boundaries.

- Phonetic information is not fully processed until around seven months of age.

- Rhythmic information is a universal aspect of all languages and aids language development.

Source: University of Cambridge

Parents should speak to their babies using sing-song speech, like nursery rhymes, as soon as possible, say researchers. That’s because babies learn languages from rhythmic information, not phonetic information, in their first months.

Phonetic information – the smallest sound elements of speech, typically represented by the alphabet – is considered by many linguists to be the foundation of language. Infants are thought to learn these small sound elements and add them together to make words. But a new study suggests that phonetic information is learnt too late and slowly for this to be the case.

Instead, rhythmic speech helps babies learn language by emphasising the boundaries of individual words and is effective even in the first months of life.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge and Trinity College Dublin investigated babies’ ability to process phonetic information during their first year.

Their study, published today in the journal Nature Communications, found that phonetic information wasn’t successfully encoded until seven months old, and was still sparse at 11 months old when babies began to say their first words.

“Our research shows that the individual sounds of speech are not processed reliably until around seven months, even though most infants can recognise familiar words like ‘bottle’ by this point,” said Cambridge neuroscientist, Professor Usha Goswami. “From then individual speech sounds are still added in very slowly – too slowly to form the basis of language.”

The researchers recorded patterns of electrical brain activity in 50 infants at four, seven and eleven months old as they watched a video of a primary school teacher singing 18 nursery rhymes to an infant. Low frequency bands of brainwaves were fed through a special algorithm, which produced a ‘read out’ of the phonological information that was being encoded.

The researchers found that phonetic encoding in babies emerged gradually over the first year of life, beginning with labial sounds (e.g. d for “daddy”) and nasal sounds (e.g. m for “mummy”), with the ‘read out’ progressively looking more like that of adults

First author, Professor Giovanni Di Liberto, a cognitive and computer scientist at Trinity College Dublin and a researcher at the ADAPT Centre, said: “This is the first evidence we have of how brain activity relates to phonetic information changes over time in response to continuous speech.”

Previously, studies have relied on comparing the responses to nonsense syllables, like “bif” and “bof” instead.

The current study forms part of the BabyRhythm project led by Goswami, which is investigating how language is learnt and how this is related to dyslexia and developmental language disorder.

Goswami believes that it is rhythmic information – the stress or emphasis on different syllables of words and the rise and fall of tone – that is the key to language learning. A sister study, also part of the BabyRhythm project, has shown that rhythmic speech information was processed by babies at two months old – and individual differences predicted later language outcomes. The experiment was also conducted with adults who showed an identical ‘read out’ of rhythm and syllables to babies.

“We believe that speech rhythm information is the hidden glue underpinning the development of a well-functioning language system,” said Goswami.

“Infants can use rhythmic information like a scaffold or skeleton to add phonetic information on to. For example, they might learn that the rhythm pattern of English words is typically strong-weak, as in ‘daddy’ or ‘mummy’, with the stress on the first syllable. They can use this rhythm pattern to guess where one word ends and another begins when listening to natural speech.”

“Parents should talk and sing to their babies as much as possible or use infant directed speech like nursery rhymes because it will make a difference to language outcome,” she added.

Goswami explained that rhythm is a universal aspect of every language all over the world. “In all language that babies are exposed to there is a strong beat structure with a strong syllable twice a second. We’re biologically programmed to emphasise this when speaking to babies.”

Goswami says that there is a long history in trying to explain dyslexia and developmental language disorder in terms of phonetic problems but that the evidence doesn’t add up. She believes that individual differences in children’s language originate with rhythm.

Funding: The research was funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and by Science Foundation Ireland.

About this neuroscience and language learning research news

Author: Charis Goodyear

Source: University of Cambridge

Contact: Charis Goodyear – University of Cambridge

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Emergence of the cortical encoding of phonetic features in the first year of life” by Giovanni Di Liberto et al. Nature Communications

Abstract

Emergence of the cortical encoding of phonetic features in the first year of life

Even prior to producing their first words, infants are developing a sophisticated speech processing system, with robust word recognition present by 4–6 months of age. These emergent linguistic skills, observed with behavioural investigations, are likely to rely on increasingly sophisticated neural underpinnings.

The infant brain is known to robustly track the speech envelope, however previous cortical tracking studies were unable to demonstrate the presence of phonetic feature encoding.

Here we utilise temporal response functions computed from electrophysiological responses to nursery rhymes to investigate the cortical encoding of phonetic features in a longitudinal cohort of infants when aged 4, 7 and 11 months, as well as adults.

The analyses reveal an increasingly detailed and acoustically invariant phonetic encoding emerging over the first year of life, providing neurophysiological evidence that the pre-verbal human cortex learns phonetic categories.

By contrast, we found no credible evidence for age-related increases in cortical tracking of the acoustic spectrogram.