Summary: Those with hereditary hemochromatosis who have two copies of the gene mutation that cause the disorder have an increased risk of developing movement disorders including Parkinson’s disease.

Source: UCSD

A disorder called hereditary hemochromatosis, caused by a gene mutation, results in the body absorbing too much iron, leading to tissue damage and conditions like liver disease, heart problems and diabetes.

Scant and conflicting research had suggested, however, that the brain was spared from iron accumulation by the blood-brain barrier, a network of blood vessels and tissue comprised of closely spaced cells that protects against invasive pathogens and toxins.

But in a new study published in the August 1, 2022 online issue of JAMA Neurology, researchers at University of California San Diego, with colleagues at UC San Francisco, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Laureate Institute for Brain Research, report that individuals with two copies of the gene mutation (one inherited from each parent) show evidence of substantial iron buildup in regions of the brain responsible for movement.

The findings suggest that the gene mutation principally responsible for hereditary hemochromatosis may be a risk factor for developing movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, which is caused by a loss of nerve cells that produce the chemical messenger dopamine.

Additionally, the researchers found that males of European descent who carry two of the gene mutations were at greatest risk; females were not.

“The sex-specific effect is consistent with other secondary disorders of hemochromatosis,” said first author Robert Loughnan, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in the Population Neuroscience and Genetics Lab at UC San Diego. “Males show a higher disease burden than females due to natural processes, such as menstruation and childbirth that expel from the body excess iron build-up in women.”

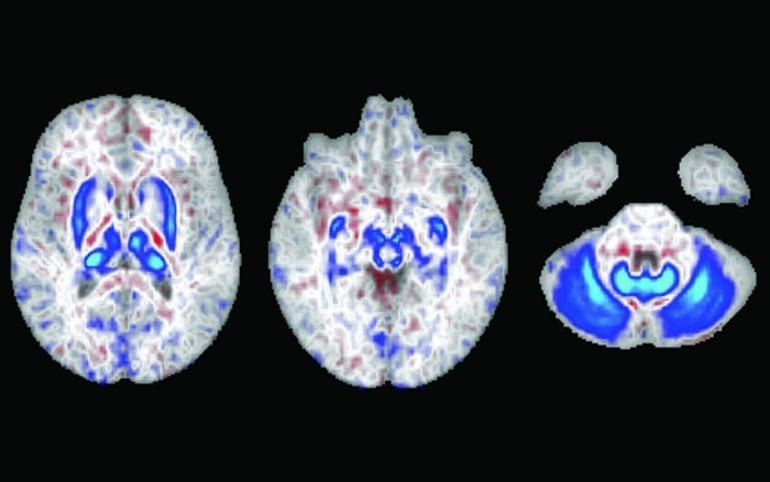

The observational study involved conducting MRI scans of 836 participants, 165 of who were at high genetic risk for developing hereditary hemochromatosis, which affects approximately 1 in 300 non-Hispanic White people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The scans detected substantial iron deposits localized to motor circuits of the brain for these high risk individuals.

The researchers then analyzed data representing almost 500,000 individuals and found that males, but not females, with high genetic risk for hemochromatosis were at 1.80-fold increased risk for developing a movement disorder, with many of these persons not having a concurrent diagnosis for hemochromatosis.

“We hope our study can bring more awareness to hemochromatosis, as many high-risk individuals are not aware of the abnormal amounts of iron accumulating in their brains,” said senior corresponding author Chun Chieh Fan, MD, PhD, an assistant adjunct professor at UC San Diego and principal investigator at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research, based in Tulsa, OK.

“Screening high-risk individuals for early detection may be helpful in determining when to intervene to avoid more severe consequences.”

Loughnan said the findings have immediate clinical import because there already exist safe and approved treatments to reduce excess iron resulting from the gene mutation. Additionally, the new data may lead to further revelations about how iron accumulates in the brain and increases the risk of movement disorders.

Approximately 60,000 Americans are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease annually, with 60 percent being male. Late-onset Parkinson’s disease (after the age of 60) is most common, but rates are rising among younger adults.

More broadly, an estimated 42 million people in the United States suffer from some form of movement disorder, such as essential tremor, dystonia and Huntington’s disease.

Co-authors include: Jonathan Ahern, Cherisse Tompkins, Clare E. Palmer, John Iversen, Terry Jernigan and Anders Dale, all at UC San Diego; Ole Andreassen, University of Oslo, Norway; Leo Sugrue, UC San Francisco; Mary ET Boyle, UC San Diego and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; and Wesley K. Thompson at UC San Diego and Laureate Institute for Brain Research.

About this genetics and neurology research news

Author: Scott La Fee

Source: UCSD

Contact: Scott La Fee – UCSD

Image: The image is credited to UCSD

Original Research: Closed access.

“Association of Genetic Variant Linked to Hemochromatosis With Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measures of Iron and Movement Disorders” by Robert Loughnan et al. JAMA Neurology

Abstract

Association of Genetic Variant Linked to Hemochromatosis With Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measures of Iron and Movement Disorders

Importance

Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that leads to iron overload. Conflicting results from previous research has led some to believe the brain is spared the toxic effects of iron in HH.

Objective

To test the association of the strongest genetic risk variant for HH on brainwide measures sensitive to iron deposition and the rates of movement disorders in a substantially larger sample than previous studies of its kind.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional retrospective study included participants from the UK Biobank, a population-based sample. Genotype, health record, and neuroimaging data were collected from January 2006 to May 2021. Data analysis was conducted from January 2021 to April 2022. Disorders tested included movement disorders (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10], codes G20-G26), abnormalities of gait and mobility (ICD-10 codes R26), and other disorders of the nervous system (ICD-10 codes G90-G99).

Exposures Homozygosity for p.C282Y, the largest known genetic risk factor for HH.

Main Outcomes and Measures

T2-weighted and T2* signal intensity from brain magnetic resonance imaging scans, measures sensitive to iron deposition, and clinical diagnosis of neurological disorders.

Results

The total cohort consisted of 488 288 individuals (264 719 female; ages 49-87 years, largely northern European ancestry), 2889 of whom were p.C282Y homozygotes. The neuroimaging analysis consisted of 836 individuals: 165 p.C282Y homozygotes (99 female) and 671 matched controls (399 female). A total of 206 individuals were excluded from analysis due to withdrawal of consent. Neuroimaging analysis showed that p.C282Y homozygosity was associated with decreased T2-weighted and T2* signal intensity in subcortical motor structures (basal ganglia, thalamus, red nucleus, and cerebellum; Cohen d >1) consistent with substantial iron deposition. Across the whole UK Biobank (2889 p.C282Y homozygotes, 485 399 controls), we found a significantly increased prevalence for movement disorders in male homozygotes (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.28-2.55; P = .001) but not female individuals (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.70-1.73; P = .69). Among the 31 p.C282Y male homozygotes with a movement disorder, only 10 had a concurrent HH diagnosis.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings indicate increased iron deposition in subcortical motor circuits in p.C282Y homozygotes and confirm an increased association with movement disorders in male homozygotes. Early treatment in HH effectively prevents the negative consequences of iron overload in the liver and heart. Our work suggests that screening for p.C282Y homozygosity in high-risk individuals also has the potential to reduce brain iron accumulation and to reduce the risk of movement disorders among male individuals who are homozygous for this mutation.