Don’t have room for dessert? The bacteria in your gut may be telling you something. Twenty minutes after a meal, gut microbes produce proteins that can suppress food intake in animals, reports a study published November 24 in Cell Metabolism. The researchers also show how these proteins injected into mice and rats act on the brain reducing appetite, suggesting that gut bacteria may help control when and how much we eat.

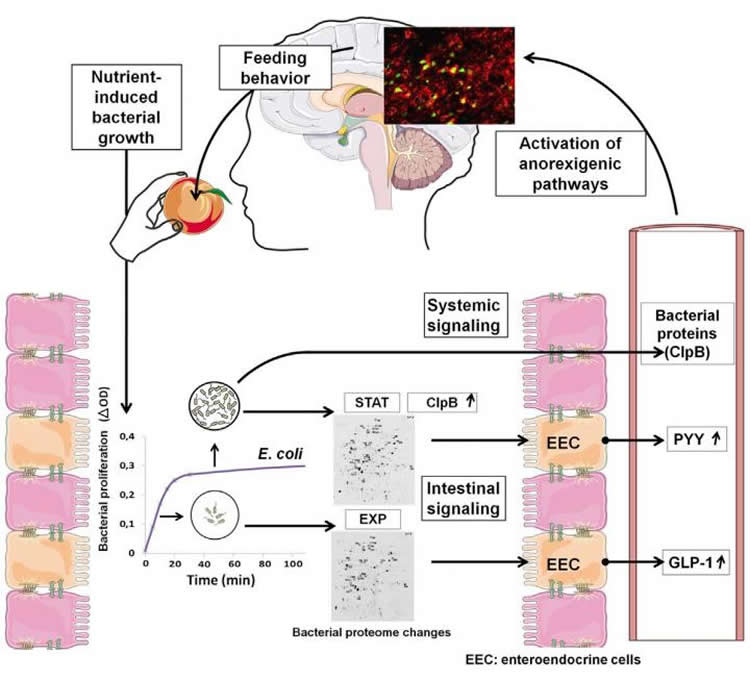

The new evidence coexists with current models of appetite control, which involve hormones from the gut signalling to brain circuits when we’re hungry or done eating. The bacterial proteins–produced by mutualistic E. coli after they’ve been satiated–were found for the first time to influence the release of gut-brain signals (e.g., GLP-1 and PYY) as well as activate appetite-regulated neurons in the brain.

“There are so many studies now that look at microbiota composition in different pathological conditions but they do not explore the mechanisms behind these associations,” says senior study author Sergueï Fetissov of Rouen University and INSERM’s Nutrition, Gut & Brain Laboratory in France. “Our study shows that bacterial proteins from E. coli can be involved in the same molecular pathways that are used by the body to signal satiety, and now we need to know how an altered gut microbiome can affect this physiology.”

Mealtime brings an influx of nutrients to the bacteria in your gut. In response, they divide and replace any members lost in the development of stool. The study raises an interesting theory: since gut microbes depend on us for a place to live, it is to their advantage for populations to remain stable. It would make sense, then, if they had a way to communicate to the host when they’re not full, promoting host to ingest nutrients again.

In the laboratory, Fetissov and colleagues found that after 20 minutes of consuming nutrients and expanding numbers, E. coli bacteria from the gut produce different kinds of proteins than they did before their feeding. The 20 minute mark seemed to coincide with the amount of time it takes for a person to begin feeling full or tired after a meal. Excited over this discovery, the researcher began to profile the bacterial proteins pre- and post-feeding.

They saw that injection of small doses of the bacterial proteins produced after feeding reduced food intake in both hungry and free-fed rats and mice. Further analysis revealed that “full” bacterial proteins stimulated the release of peptide YY, a hormone associated with satiety, while “hungry” bacterial hormones did not. The opposite was true for glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a hormone known to simulate insulin release.

The investigators next developed an assay that could detect the presence of one of the “full” bacterial proteins, called ClpB in animal blood. Although blood levels of the protein in mice and rats detected 20 minutes after meal consumption did not change, it correlated with ClpB DNA production in the gut, suggesting that it may link gut bacterial composition with the host control of appetite. The researchers also found that ClpB increased firing of neurons that reduce appetite. The role of other E.coli proteins in hunger and satiation, as well as how proteins from other species of bacteria may contribute, is still unknown.

“We now think bacteria physiologically participate in appetite regulation immediately after nutrient provision by multiplying and stimulating the release of satiety hormones from the gut,” Fetisov says. “In addition, we believe gut microbiota produce proteins that can be present in the blood longer term and modulate pathways in the brain.”

Funding: This work received support from the EU INTERREG IVA 2 Seas Program; Haute-Normandie Region, France; and the Marie Curie CIG NeuROSens.

Source: Joseph Caputo – Cell Press

Image Credit: The images are credited to J. Breton, N. Lucas & D. Schapman and Breton et al./Cell Metabolism 2015

Original Research: Abstract for “Gut Commensal E. coli Proteins Activate Host Satiety Pathways following Nutrient-Induced Bacterial Growth” by Jonathan Breton, Naouel Tennoune, Nicolas Lucas, Marie Francois, Romain Legrand, Justine Jacquemot, Alexis Goichon, Charlène Guérin, Johann Peltier, Martine Pestel-Caron, Philippe Chan, David Vaudry, Jean-Claude do Rego, Fabienne Liénard, Luc Pénicaud, Xavier Fioramonti, Ivor S. Ebenezer, Tomas Hökfelt, Pierre Déchelotte, and Sergueï O. Fetissov in Cell Metabloism. Published online November 24 2015 doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.017

Abstract

Gut Commensal E. coli Proteins Activate Host Satiety Pathways following Nutrient-Induced Bacterial Growth

The composition of gut microbiota has been associated with host metabolic phenotypes, but it is not known if gut bacteria may influence host appetite. Here we show that regular nutrient provision stabilizes exponential growth of E. coli, with the stationary phase occurring 20 min after nutrient supply accompanied by bacterial proteome changes, suggesting involvement of bacterial proteins in host satiety. Indeed, intestinal infusions of E. coli stationary phase proteins increased plasma PYY and their intraperitoneal injections suppressed acutely food intake and activated c-Fos in hypothalamic POMC neurons, while their repeated administrations reduced meal size. ClpB, a bacterial protein mimetic of α-MSH, was upregulated in the E. coli stationary phase, was detected in plasma proportional to ClpB DNA in feces, and stimulated firing rate of hypothalamic POMC neurons. Thus, these data show that bacterial proteins produced after nutrient-induced E. coli growth may signal meal termination. Furthermore, continuous exposure to E. coli proteins may influence long-term meal pattern.

“Gut Commensal E. coli Proteins Activate Host Satiety Pathways following Nutrient-Induced Bacterial Growth” by Jonathan Breton, Naouel Tennoune, Nicolas Lucas, Marie Francois, Romain Legrand, Justine Jacquemot, Alexis Goichon, Charlène Guérin, Johann Peltier, Martine Pestel-Caron, Philippe Chan, David Vaudry, Jean-Claude do Rego, Fabienne Liénard, Luc Pénicaud, Xavier Fioramonti, Ivor S. Ebenezer, Tomas Hökfelt, Pierre Déchelotte, and Sergueï O. Fetissov in Cell Metabloism. Published online November 24 2015 doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.017