Summary: Study reveals striking similarities in both behaviors and neuroanatomical changes between people with schizophrenia and behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia.

Source: Max Planck Institute

Researchers have, for the first time, compared schizophrenia and frontotemporal dementia—disorders that are both located in the frontal and temporal lobe regions of the brain.

The idea can be traced back to Emil Kraepelin, who coined the term “dementia praecox” in 1899 to describe the progressive mental and emotional decline of young patients. His approach was quickly challenged, as only 25% of those affected showed this form of disease progression.

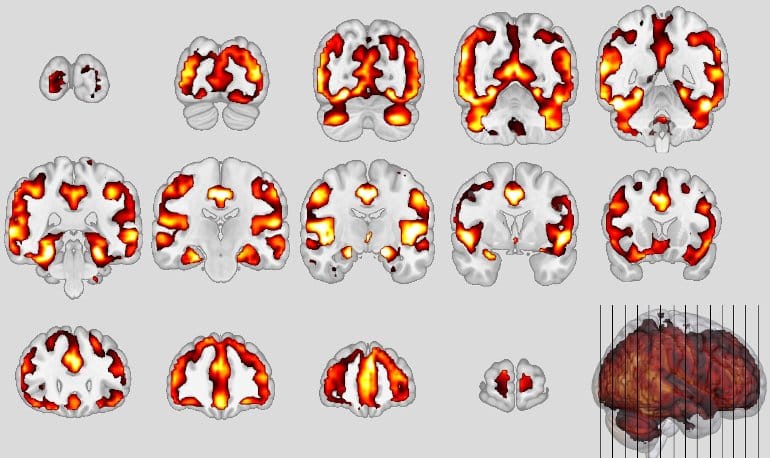

But now, with the help of imaging and machine learning, scientists have found the first valid indications of neuroanatomical patterns in the brain that resemble the signature of patients with frontotemporal dementia.

It is rare that scientists in basic research go back to seemingly obsolete findings that are more than 120 years old. In the case of Nikolaos Koutsouleris and Matthias Schroeter, who are researchers and physicians, this was even a drive.

It´s about Emil Kraepelin, founder of the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry (MPI) as well as the psychiatric hospital of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU), and his term “dementia praecox,” coined in 1899.

This was his definition for young adults who increasingly withdraw from reality and fall into an irreversible, dementia-like state. Kraepelin lived to see his concept refuted.

By the beginning of the 20th century, experts were beginning to use the term “schizophrenia” for these patients, since the disease does not take such a bad course in all persons concerned.

Kraepelin had the idea of a frontotemporal disease, he assumed that the reason for the sometimes-debilitating course of the patients is located in the frontal and temporal lobe areas of the brain. That’s where personality, social behavior and empathy are controlled.

“But this idea was lost as no pathological evidence for neurodegenerative processes seen in Alzheimer’s Disease was found in the brains of these patients,” says Koutsouleris, who works at Kraepelin’s places of work, the MPI and LMU.

He continues: “Ever since I became a psychiatrist, I wanted to work on this question.” Fifteen years later, with sufficiently large data sets, imaging techniques and machine learning algorithms, the professor had the tools at hand to potentially find answers.”

He had found the right partner in Matthias Schroeter, who studies neurodegenerative diseases, specifically frontotemporal dementias, at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences.

Similarities between schizophrenia and frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), especially the behavioral variant (bvFTD), is difficult to recognize in its early stages because it is often confused with schizophrenia. Thus, the similarities are obvious: in sufferers of both groups, personality as well as behavioral changes occur.

An often dramatic development for affected persons and relatives sets in. Since both disorders are located in the frontal, temporal and insular regions of the brain, it was obvious to compare them directly as well.

“They seem to be on a similar symptom spectrum, so we wanted to look for common signatures or patterns in the brain,” Koutsouleris says, describing his plan.

With an international team, Koutsouleris and Schroeter used artificial intelligence to train neuroanatomical classifiers of both disorders, which they applied to brain data from different cohorts.

The result, just published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry, was that 41% of schizophrenia patients met the classifier’s criteria for bvFTD.

“When we saw this in schizophrenic patients as well, it rang a bell—indicating a similarity between the two disorders,” Koutsouleris and Schroeter recall.

The research team found that the higher the patients’ bvFTD score, which measured the similarity between the two disorders, the more likely they were to have a “bvFTD-like” phenotype and the less likely they were to improve their symptoms over two years.

A 23-year-old patient does not recover

“I just wanted to know why my 23-year-old patient with onset symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations, delusions, and cognitive deficits, had not improved at all, even after two years, while another who started out just as bad was continuing his education and had found a girlfriend. Again and again, I saw these young people who did not recover at all,” Koutsouleris says.

When the researchers also checked the correlations in high-risk patients such as the 23-year-old, they found confirmation at the neuroanatomical level of what Kraepelin had been the first to decisively describe: no improvement whatsoever in the condition of some patients, quite the opposite.

Similar neuronal structures were affected, in particular the so-called default mode network and the salience network of the brain, responsible for attention control, empathy and social behavior, showed volume decreases in the gray matter area that houses the neurons. In bvFTD, certain neurons (von Economo neurons) perish; in schizophrenia, these neurons are also altered. This was reflected by the neuroanatomical score: after one year, it had doubled in these severely affected persons.

As a comparison, the scientists had also calculated the Alzheimer’s score using a specific classifier and did not find these effects there.

“This means that the concept of dementia praecox can no longer be completely wiped away; we provide the first valid evidence that Kraepelin was not wrong, at least in some of the patients,” Schroeter says.

Today, or in the near future, this means that experts will be able to predict which subgroup patients belong to.

“Then intensive therapeutic support can be initiated at an early stage to exploit any remaining recovery potential,” Koutsouleris says.

In addition, new personalized therapies could be developed for this subgroup that promote a proper maturation and connectivity of the affected neurons and prevent their progressive destruction as part of the disease process.

About this schizophrenia and dementia research news

Author: Press Office

Source: Max Planck Institute

Contact: Press Office – Max Planck Institute

Image: The image is credited to Koutsouleris

Original Research: Closed access.

“Exploring Links Between Psychosis and Frontotemporal Dementia Using Multimodal Machine Learning” by Nikolaos Koutsouleris et al. JAMA Psychiatry

Abstract

Exploring Links Between Psychosis and Frontotemporal Dementia Using Multimodal Machine Learning

Importance

The behavioral and cognitive symptoms of severe psychotic disorders overlap with those seen in dementia. However, shared brain alterations remain disputed, and their relevance for patients in at-risk disease stages has not been explored so far.

Objective

To use machine learning to compare the expression of structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) patterns of behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), Alzheimer disease (AD), and schizophrenia; estimate predictability in patients with bvFTD and schizophrenia based on sociodemographic, clinical, and biological data; and examine prognostic value, genetic underpinnings, and progression in patients with clinical high-risk (CHR) states for psychosis or recent-onset depression (ROD).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study included 1870 individuals from 5 cohorts, including (1) patients with bvFTD (n = 108), established AD (n = 44), mild cognitive impairment or early-stage AD (n = 96), schizophrenia (n = 157), or major depression (n = 102) to derive and compare diagnostic patterns and (2) patients with CHR (n = 160) or ROD (n = 161) to test patterns’ prognostic relevance and progression. Healthy individuals (n = 1042) were used for age-related and cohort-related data calibration. Data were collected from January 1996 to July 2019 and analyzed between April 2020 and April 2022.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Case assignments based on diagnostic patterns; sociodemographic, clinical, and biological data; 2-year functional outcomes and genetic separability of patients with CHR and ROD with high vs low pattern expression; and pattern progression from baseline to follow-up MRI scans in patients with nonrecovery vs preserved recovery.

Results

Of 1870 included patients, 902 (48.2%) were female, and the mean (SD) age was 38.0 (19.3) years. The bvFTD pattern comprising prefrontal, insular, and limbic volume reductions was more expressed in patients with schizophrenia (65 of 157 [41.2%]) and major depression (22 of 102 [21.6%]) than the temporo-limbic AD patterns (28 of 157 [17.8%] and 3 of 102 [2.9%], respectively). bvFTD expression was predicted by high body mass index, psychomotor slowing, affective disinhibition, and paranoid ideation (R2 = 0.11). The schizophrenia pattern was expressed in 92 of 108 patients (85.5%) with bvFTD and was linked to the C9orf72 variant, oligoclonal banding in the cerebrospinal fluid, cognitive impairment, and younger age (R2 = 0.29). bvFTD and schizophrenia pattern expressions forecasted 2-year psychosocial impairments in patients with CHR and were predicted by polygenic risk scores for frontotemporal dementia, AD, and schizophrenia. Findings were not associated with AD or accelerated brain aging. Finally, 1-year bvFTD/schizophrenia pattern progression distinguished patients with nonrecovery from those with preserved recovery.

Conclusions and Relevance

Neurobiological links may exist between bvFTD and psychosis focusing on prefrontal and salience system alterations. Further transdiagnostic investigations are needed to identify shared pathophysiological processes underlying the neuroanatomical interface between the 2 disease spectra.