Summary: Face pareidolia, a phenomenon where the brain is tricked into seeing human faces in inanimate objects, may occur as a result of the brain processing the perceived facial expression in the same sequential way it perceives a human face.

Source: University of Sydney

It’s so commonplace we barely give it a second thought, but human brains seem hardwired to see human faces where there are none — in objects as varied as the moon, toys, plastic bottles, tree trunks and vacuum cleaners. Some have even seen an imagined Jesus in cheese on toast.

Until now scientists haven’t understood exactly what the brain is doing when it processes visual signals and interprets them as representations of the human face.

Neuroscientists at the University of Sydney now say how our brains identify and analyse real human faces is conducted by the same cognitive processes that identify illusory faces.

“From an evolutionary perspective, it seems that the benefit of never missing a face far outweighs the errors where inanimate objects are seen as faces,” said Professor David Alais lead author of the study from the School of Psychology.

“There is a great benefit in detecting faces quickly,” he said, “but the system plays ‘fast and loose’ by applying a crude template of two eyes over a nose and mouth. Lots of things can satisfy that template and thus trigger a face detection response.”

This facial recognition response happens lightning fast in the brain: within a few hundred milliseconds.

“We know these objects are not truly faces, yet the perception of a face lingers,” Professor Alais said. “We end up with something strange: a parallel experience that it is both a compelling face and an object. Two things at once. The first impression of a face does not give way to the second perception of an object.”

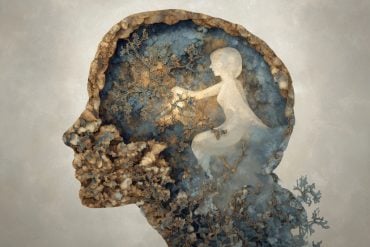

This error is known as “face pareidolia.” It is such a common occurrence that we accept the notion of detecting faces in objects as ‘normal’ — but humans do not experience this cognitive process as strongly for other phenomena.

The brain has evolved specialised neural mechanisms to rapidly detect faces and it exploits the common facial structure as a short-cut for rapid detection.

“Pareidolia faces are not discarded as false detections but undergo facial expression analysis in the same way as real faces,” Professor Alais said.

Not only do we imagine faces, we analyse them and give them emotional attributes.

The findings are published today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The researchers say this expression analysis of inanimate objects is because as deeply social beings, simply detecting a face isn’t enough.

“We need to read the identity of the face and discern its expression. Are they a friend or a foe? Are they happy, sad, angry, pained?” Professor Alais said.

What the study examined was whether once a pareidolia face is detected, it is subsequently analysed for facial expression, or discarded from face processing as a false detection.

The research shows that once a false face is retained by the brain it is analysed for its facial expression in the same way that a real face is.

“We showed this by presenting sequences of faces and having participants rate each face’s expression on a scale ranging from angry to happy,” Professor Alais said.

What was intriguing is that a known bias in judging human faces persisted with analysis of inanimate imagined faces.

A previous study undertaken by Professor Alais showed that in a Tinder-like situation of judging face after face, a bias is observed whereby the assessment of the current face is influenced by our assessment of the previous face.

The scientists tested this by mixing up real faces with pareidolia faces — and the result was the same.

“This ‘cross-over’ condition is important as it shows the same underlying facial expression process is involved regardless of image type,” Professor Alais said.

“This means that seeing faces in clouds is more than a child’s fantasy,” he said.

“When objects look compellingly face-like, it is more than an interpretation: they really are driving your brain’s face detection network. And that scowl, or smile; that’s your brain’s facial expression system at work. For the brain, fake or real, faces are all processed the same way.”

About this facial processing research news

Source: University of Sydney

Contact: Press Office – University of Sydney

Image: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Open access.

“A shared mechanism for facial expression in human faces and face pareidolia” by David Alais, Yiben Xu, Susan G. Wardle, Jessica Taubert. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences

Abstract

A shared mechanism for facial expression in human faces and face pareidolia

Facial expressions are vital for social communication, yet the underlying mechanisms are still being discovered. Illusory faces perceived in objects (face pareidolia) are errors of face detection that share some neural mechanisms with human face processing. However, it is unknown whether expression in illusory faces engages the same mechanisms as human faces.

Here, using a serial dependence paradigm, we investigated whether illusory and human faces share a common expression mechanism.

First, we found that images of face pareidolia are reliably rated for expression, within and between observers, despite varying greatly in visual features.

Second, they exhibit positive serial dependence for perceived facial expression, meaning an illusory face (happy or angry) is perceived as more similar in expression to the preceding one, just as seen for human faces. This suggests illusory and human faces engage similar mechanisms of temporal continuity.

Third, we found robust cross-domain serial dependence of perceived expression between illusory and human faces when they were interleaved, with serial effects larger when illusory faces preceded human faces than the reverse.

Together, the results support a shared mechanism for facial expression between human faces and illusory faces and suggest that expression processing is not tightly bound to human facial features.