Summary: Eating late, or at inappropriate times might have a significant impact on both weight and normal sleep-wake patterns, a new study published in Cell Metabolism reports.

Source: UT Southwestern Medical Center.

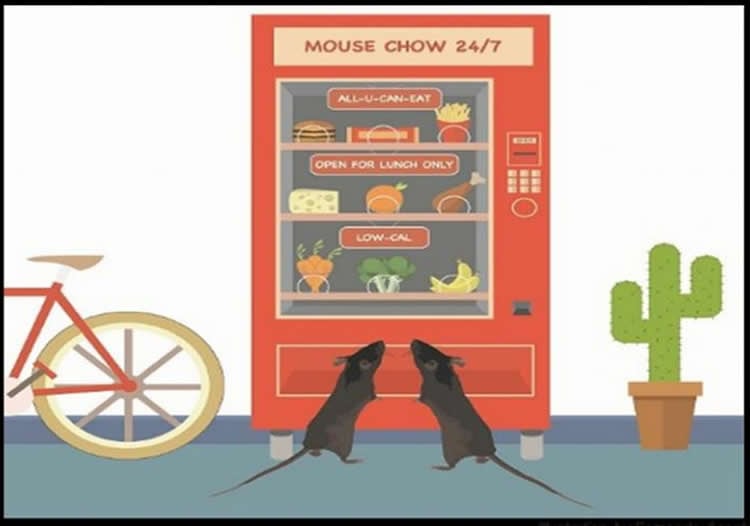

A new high-precision feeding system for lab mice reinforces the idea that the time of day food is eaten is more critical to weight loss than the amount of calories ingested.

Mice on a reduced calorie plan that ate only during their normal feeding/active cycle were the only ones among five groups to lose weight, despite consuming the same amount as another group fed during their rest time in daylight, according to the study at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

“Translated into human behavior, these studies suggest that dieting will only be effective if calories are consumed during the daytime when we are awake and active. They further suggest that eating at the wrong time at night will not lead to weight loss even when dieting,” said Dr. Joseph S. Takahashi, Chairman of Neuroscience at UT Southwestern’s Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute and Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Using high-tech sensors and automated feeding equipment, scientists developed the feeding system to help answer the difficult question of why calorie-restricted diets improve longevity. They say the new set of tools has already offered fresh insights.

Among the findings published in Cell Metabolism, scientists documented how mice on a diet reduced their eating to a very short time period and were unexpectedly active during the day – the normal rest period for the nocturnal animals. These data reveal previously unknown relationships among feeding, metabolism, and behavior.

“It has been known for decades that caloric restriction prolongs lifespan in animals, but these types of studies are very difficult to conduct because they required manual feeding of subjects over many years. Therefore, shortcuts were taken in order to deal with practical matters such as the normal Monday-to-Friday work week,” said Dr. Takahashi, holder of the Loyd B. Sands Distinguished Chair in Neuroscience.

Besides affecting weight, scientists believe the timing of food consumption affects one’s circadian rhythms and may be the route by which dietary habits impact lifespan. The study reinforced this notion by testing the day/night cycles of mice under different feeding schedules.

Two groups of mice that were fed at the wrong times during their normal light-dark cycle – those with a 30 percent calorie reduction and others with unlimited food access during the day – remained active at night, suggesting they might have chronic sleep deprivation.

This is an especially important factor for scientists to consider for future research, given that many calorie-reduction studies involve only daytime feeding, which is the wrong time for otherwise nocturnal mice. Without accounting for the timing of food intake, research that examines the effects of calorie reduction on lifespan may be skewed by hidden factors such as lack of sleep and desynchronized circadian rhythms.

Dr. Takahashi said the automated system developed for this latest study helped his team address this issue and other confounding variables that have inhibited previous research, including the varied amounts of food given and how quickly it is consumed.

“Despite the importance of these factors, manipulating when and how much food is available for extended periods has been difficult in past research. This automated system, which can be scaled up for large and very long longevity studies, provides the means to address open questions about what mechanisms extend lifespan in mammals, and whether it is actually the calorie reduction or the time at which food is consumed that extends lifespan,” Dr. Takahashi said.

Funding:The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). Other collaborators in UT Southwestern’s Department of Neuroscience include Dr. Carla Green, Professor, Distinguished Scholar in Neuroscience; Dr. Victoria A. Acosta-Rodríguez, Postdoctoral Researcher; Dr. Marleen H.M. de Groot, Research Specialist with HHMI; and Dr. Filipa Rijo-Ferreira, Associate with HHMI.

Source: James Beltran – UT Southwestern Medical Center

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Fernando Agosto.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Mice under Caloric Restriction Self-Impose a Temporal Restriction of Food Intake as Revealed by an Automated Feeder System” by Victoria A. Acosta-Rodríguez, Marleen H.M. de Groot, Filipa Rijo-Ferreira, Carla B. Green, and Joseph S. Takahashi in Cell Metabolism. Published online July 5 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.007

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]UT Southwestern Medical Center “Eating at ‘Wrong Time’ Affects Body Weight and Circadian Rhythm.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 18 July 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/body-weight-circadian-eating-time-7115/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]UT Southwestern Medical Center (2017, July 18). Eating at ‘Wrong Time’ Affects Body Weight and Circadian Rhythm. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved July 18, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/body-weight-circadian-eating-time-7115/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]UT Southwestern Medical Center “Eating at ‘Wrong Time’ Affects Body Weight and Circadian Rhythm.” https://neurosciencenews.com/body-weight-circadian-eating-time-7115/ (accessed July 18, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Mice under Caloric Restriction Self-Impose a Temporal Restriction of Food Intake as Revealed by an Automated Feeder System

Caloric restriction (CR) extends lifespan in mammals, yet the mechanisms underlying its beneficial effects remain unknown. The manner in which CR has been implemented in longevity experiments is variable, with both timing and frequency of meals constrained by work schedules. It is commonplace to find that nocturnal rodents are fed during the daytime and meals are spaced out, introducing prolonged fasting intervals. Since implementation of feeding paradigms over the lifetime is logistically difficult, automation is critical, but existing systems are expensive and not amenable to scale. We have developed a system that controls duration, amount, and timing of food availability and records feeding and voluntary wheel-running activity in mice. Using this system, mice were exposed to temporal or caloric restriction protocols. Mice under CR self-imposed a temporal component by consolidating food intake and unexpectedly increasing wheel-running activity during the rest phase, revealing previously unrecognized relationships among feeding, metabolism, and behavior.

“Mice under Caloric Restriction Self-Impose a Temporal Restriction of Food Intake as Revealed by an Automated Feeder System” by Victoria A. Acosta-Rodríguez, Marleen H.M. de Groot, Filipa Rijo-Ferreira, Carla B. Green, and Joseph S. Takahashi in Cell Metabolism. Published online July 5 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.007