Summary: Those who experience chronic adversity throughout life have impaired ability to produce sufficient dopamine levels to help them cope with stressful situations.

Source: eLife

People exposed to a lifetime of psychosocial adversity may have an impaired ability to produce the dopamine levels needed for coping with acutely stressful situations.

These findings, published today in eLife, may help explain why long-term exposure to psychological trauma and abuse increases the risk of mental illness and addiction.

“We already know that chronic psychosocial adversity can induce vulnerability to mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression,” explains lead author Dr Michael Bloomfield, Excellence Fellow and leader of the Translational Psychiatry Research Group at University College London, UK. “What we’re missing is a precise mechanistic understanding of how this risk is increased.”

To address this question, Dr Bloomfield and his colleagues used an imaging technique called positron emission tomography (PET) to compare the production of dopamine in 34 volunteers exposed to an acute stress. Half of the participants had a high lifetime exposure to psychosocial stress, while the other half had low exposure. All of them undertook the Montréal Imaging Stress Task, which involved receiving criticism as they tried to complete mental arithmetic.

Two hours after this stress task, the participants were injected with small amounts of a radioactive tracer that allowed the scientists to view dopamine production in their brains using PET. The scans revealed that in those with low exposure to chronic adversity, dopamine production was proportional to the degree of threat that the person perceived.

In people with high exposure to chronic adversity, however, the perception of threat was exaggerated whilst their production of dopamine was impaired. The researchers found that other physiological responses to stress were also dampened in this group. For example, their blood pressure and cortisol levels did not increase as much as in the low-adversity group in response to stress.

“This study can’t prove that chronic psychosocial stress causes mental illness or substance abuse later in life by lowering dopamine levels,” Dr Bloomfield cautions. “But we have provided a plausible mechanism for how chronic stress may increase the risk of mental illnesses by altering the brain’s dopamine system.”

“Further work is now needed to better understand how changes in the dopamine system caused by adversity can lead to vulnerability towards mental illnesses and addiction,” adds senior author Oliver Howes, Professor of Molecular Psychiatry at MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences and King’s College London, UK.

Source:

eLife

Media Contacts:

Emily Packer – eLife

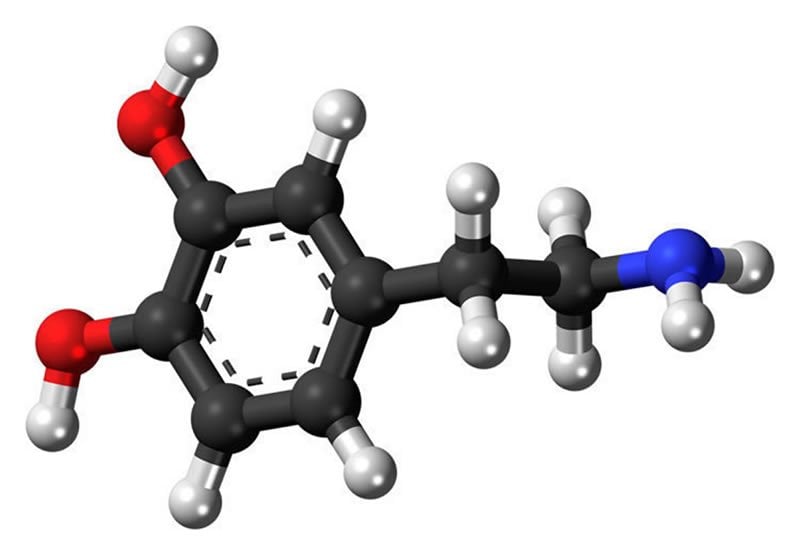

Image Source:

The image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Open access

“The effects of psychosocial stress on dopaminergic function and the acute stress response”. Michael AP Bloomfield, Robert A McCutcheon, Matthew Kempton, Tom P Freeman, Oliver Howes.

eLife doi:10.7554/eLife.46797.

Abstract

The effects of psychosocial stress on dopaminergic function and the acute stress response

Chronic psychosocial adversity induces vulnerability to mental illnesses. Animal studies demonstrate that this may be mediated by dopaminergic dysfunction. We therefore investigated whether long-term exposure to psychosocial adversity was associated with dopamine dysfunction and its relationship to psychological and physiological responses to acute stress. Using 3,4-dihydroxy-6-[18F]-fluoro-l-phenylalanine ([18F]-DOPA) positron emission tomography (PET), we compared dopamine synthesis capacity in n = 17 human participants with high cumulative exposure to psychosocial adversity with n = 17 age- and sex-matched participants with low cumulative exposure. The PET scan took place 2 hr after the induction of acute psychosocial stress using the Montréal Imaging Stress Task to induce acute psychosocial stress. We found that dopamine synthesis correlated with subjective threat and physiological response to acute psychosocial stress in the low exposure group. Long-term exposure to psychosocial adversity was associated with dampened striatal dopaminergic function (p=0.03, d = 0.80) and that psychosocial adversity blunted physiological yet potentiated subjective responses to acute psychosocial stress. Future studies should investigate the roles of these changes in vulnerability to mental illnesses.