Summary: Researchers explore emerging strategies for planting brain-altering bacteria in the gut to provide mental benefits.

Source: Cell Press.

Now that we know that gut bacteria can speak to the brain — in ways that affect our mood, our appetite, and even our circadian rhythms — the next challenge for scientists is to control this communication. The science of psychobiotics, reviewed October 25 in Trends in Neurosciences, explores emerging strategies for planting brain-altering bacteria in the gut to provide mental benefits and the challenges ahead in understanding how such products could work for humans.

Psychobiotics is a recent term. While it’s been known for over a century that bacteria can have positive effects on physical health, only studies in the last 10-15 years have shown that there is a gut-brain connection. In mice, enhanced immune function, better reactions to stress, and even learning and memory advantages have been attributed to adding the right strain of bacteria. Human studies are more difficult to interpret because mood changes in response to probiotics are self-reported, but physiological changes, such as reduced cortical levels and inflammation, have been observed.

“Those studies give us confidence that gut bacteria are playing a causal role in very important biological processes, which we can then hope to exploit with psychobiotics,” says Review lead author Philip Burnet, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford. “We’re now on the search for mechanisms, mainly in animal models. The human studies are provocative and exciting, but ultimately, most have small sample sizes, so their replicability is difficult to estimate at present. As they say, we’re ‘cautiously optimistic.'”

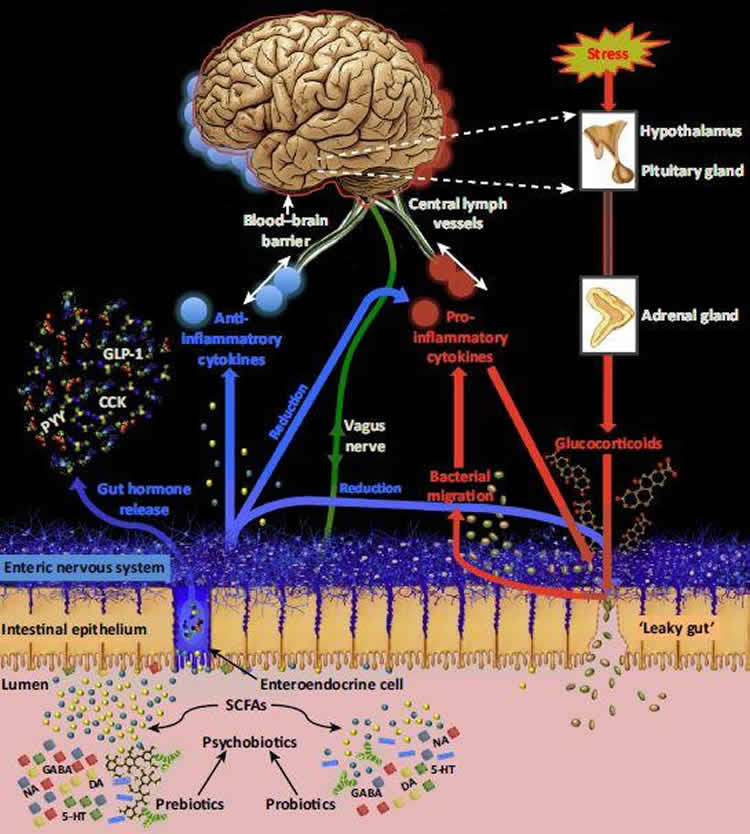

Researchers seem to agree that the key players responsible for the bacteria-gut-brain axis — the nervous system of the intestines, the immune system, the vagus nerve, and possibly gut hormones and neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin and dopamine) — are involved. What varies is the excitement about the use of psychobiotics as methods of treatment for psychological disorders and enhancing cognition. For example, in mice we know that psychobiotics often increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is closely linked to learning and memory. At present, we have no way of knowing whether psychobiotics affect BDNF in humans, and a systematic review recently found no overall benefit of probiotic ingestion in humans.

However, probiotics are only part of the story. “Prebiotics (nutrition for gut bacteria) are another channel to alter gut bacteria,” Burnet says. “We call for an even further widening of the definition of ‘psychobiotics’ to include drugs such as antidepressants and antipsychotics, and activities such as exercise and eating, because of their effects on gut bacteria.”

For now, consumers of probiotics and prebiotics should be skeptical about products currently advertised to have psychobiotic effects. Such supplements have a lot of promise as “add-on” therapies for antidepressants or antipsychotics, but many more questions need to be answered about what strains of bacteria offer specific benefits, how they work, whether they offset other benefits, and how they will be regulated.

“Psychobiotics are a long way from their true translational potential. It’s a little boring to say that we need more studies, but that is always the case in any academic discipline,” Burnet says. “The technology and resources already exist for such investigations, so though we are enthusiastic, the enthusiasm needs to be tempered and channeled toward answering the core mechanistic questions.”

Source: Joseph Caputo – Cell Press

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Sarkar et al./Trends in Neurosciences 2016.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria–Gut–Brain Signals” by Amar Sarkar, Soili M. Lehto, Siobhán Harty, Timothy G. Dinan, John F. Cryan, and Philip W.J. Burnet in Trends in Neurosciences. Published online October 25 2016 doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.09.002

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Cell Press “The Current State of Psychobiotics.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 25 October 2016.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/psychobiotics-neuroscience-5352/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Cell Press (2016, October 25). The Current State of Psychobiotics. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved October 25, 2016 from https://neurosciencenews.com/psychobiotics-neuroscience-5352/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Cell Press “The Current State of Psychobiotics.” https://neurosciencenews.com/psychobiotics-neuroscience-5352/ (accessed October 25, 2016).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria–Gut–Brain Signals

Psychobiotics were previously defined as live bacteria (probiotics) which, when ingested, confer mental health benefits through interactions with commensal gut bacteria. We expand this definition to encompass prebiotics, which enhance the growth of beneficial gut bacteria. We review probiotic and prebiotic effects on emotional, cognitive, systemic, and neural variables relevant to health and disease. We discuss gut–brain signalling mechanisms enabling psychobiotic effects, such as metabolite production. Overall, knowledge of how the microbiome responds to exogenous influence remains limited. We tabulate several important research questions and issues, exploration of which will generate both mechanistic insights and facilitate future psychobiotic development. We suggest the definition of psychobiotics be expanded beyond probiotics and prebiotics to include other means of influencing the microbiome.

Trends

Psychobiotics are beneficial bacteria (probiotics) or support for such bacteria (prebiotics) that influence bacteria–brain relationships.

Psychobiotics exert anxiolytic and antidepressant effects characterised by changes in emotional, cognitive, systemic, and neural indices. Bacteria–brain communication channels through which psychobiotics exert effects include the enteric nervous system and the immune system.

Current unknowns include dose-responses and long-term effects.

The definition of psychobiotics should be expanded to any exogenous influence whose effect on the brain is bacterially-mediated.

“Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria–Gut–Brain Signals” by Amar Sarkar, Soili M. Lehto, Siobhán Harty, Timothy G. Dinan, John F. Cryan, and Philip W.J. Burnet in Trends in Neurosciences. Published online October 25 2016 doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.09.002