Summary: A new study reveals that insufficient vitamin K may harm brain health and memory as we age. In rodent models, a vitamin K-deficient diet led to increased brain inflammation and fewer newly formed neurons in the hippocampus—key factors in learning and memory.

Mice with low vitamin K struggled with memory and spatial learning tasks, indicating clear cognitive deficits. Researchers stress the importance of a healthy diet rich in leafy greens rather than relying on supplements to support brain health during aging.

Key Facts:

- Impaired Memory: Mice on a low-vitamin K diet performed poorly on memory and learning tests.

- Reduced Neurogenesis: Vitamin K deficiency decreased new neuron formation in the hippocampus.

- Increased Inflammation: Deficient mice showed more activated microglia, indicating brain inflammation.

Source: Tufts University

As scientists seek to unravel the intricate potential connections between nutrition and the aging brain, a new study from researchers at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (HNRCA) at Tufts University is shedding light on how insufficient consumption of vitamin K may adversely affect cognition as people get older.

The study, conducted in middle-aged rodents, suggests that a lack of vitamin K may increase inflammation and hamper proliferation of neural cells in the hippocampus, a portion of the brain that is capable of generating new cells and is central to functions such as learning and memory.

Video credit: Neuroscience News

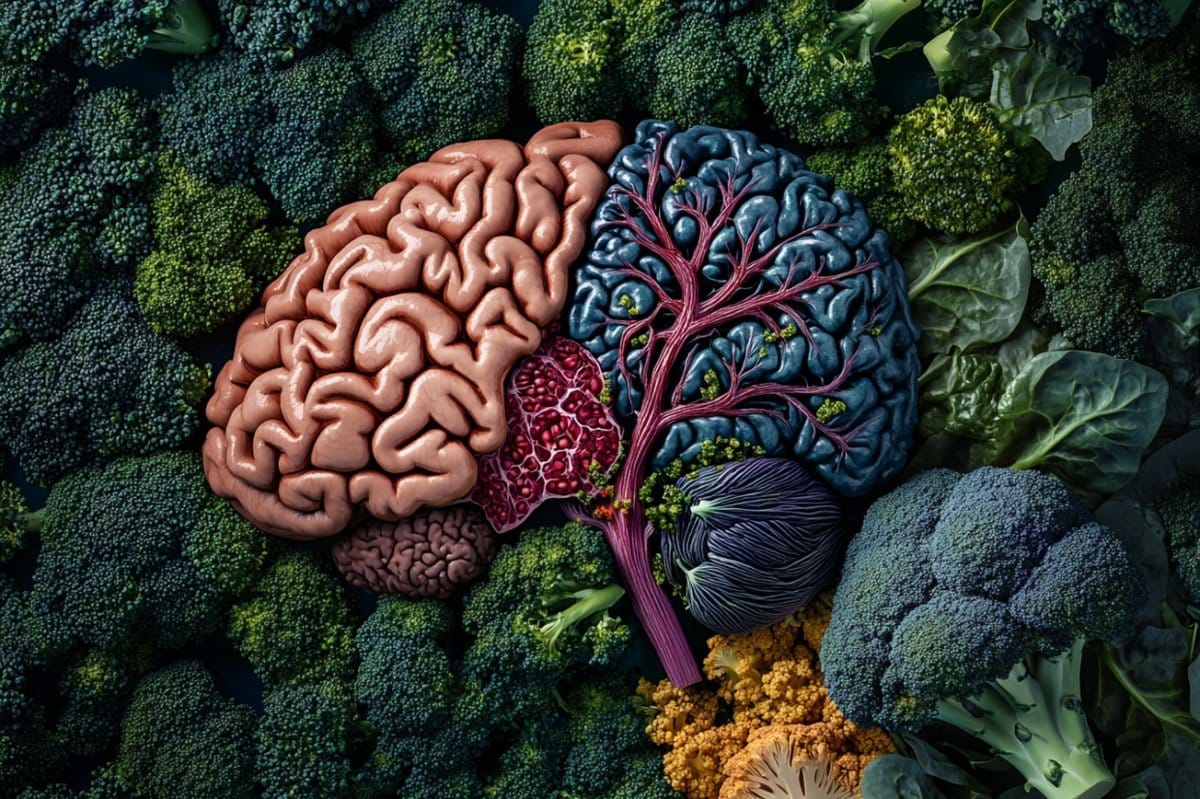

Vitamin K is found in green leafy vegetables such as Brussels sprouts, broccoli, green peas, kale, and spinach. It is already known to play an essential role in blood clotting, and research suggests it may also have positive effects on cardiovascular health as well as joint health, says Sarah Booth, director of the HNRCA and senior author of the study. Booth is also a professor at the Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University.

“There is also research that indicates vitamin K contributes to brain function and that brain function declines during the aging process,” says Tong Zheng, lead author of the study and a research scientist at the HNRCA.

“Vitamin K seems to have a protective effect. Our research is trying to understand the underlying mechanism for that effect, so that we might one day be able to target those mechanisms specifically.”

Learning and Memory Affected

In the new research, published in the Journal of Nutrition, researchers conducted a six-month dietary intervention to compare the cognitive performance of mice that were fed a low-vitamin K diet and those receiving a standard diet.

The research team focused on menaquinone-4, a form of vitamin K prevalent in brain tissue, and found significantly lower levels of this nutrient in the brains of the vitamin K-deficient mice.

This deficiency is associated with noticeable cognitive decline as measured in a series of behavioral tests designed to assess their learning and memory.

In one such test, the novel object recognition test, the vitamin K-deficient mice showed a diminished ability to distinguish between familiar and new objects, a clear indication of impaired memory.

In a second test, to measure spatial learning, the mice were tasked with learning the location of a hidden platform in a pool of water. The vitamin K-deficient mice took considerably longer to learn the task compared to their counterparts with adequate vitamin K levels.

When the researchers then examined the mice brain tissue, they found significant changes within the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for learning and memory.

Specifically, they observed a reduced number of proliferating cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in the vitamin K-deficient mice. This decrease translated to fewer newly generated immature neurons, a process known as neurogenesis.

“Neurogenesis is thought to play a critical role in learning and memory, and its impairment could directly contribute to the cognitive decline observed in the study,” Zheng says.

Adding another layer of complexity, the researchers also found evidence of increased neuroinflammation in the brains of the vitamin K-deficient mice.

“We found a higher number of activated microglia, which are the major immune cells in the brain,” says Zheng.

While microglia play a vital role in maintaining brain health, their overactivation can lead to chronic inflammation, which is increasingly recognized as a key factor in age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases.

A Healthy Diet

Both Booth and Zheng emphasize that their research doesn’t mean that people should rush out and start taking vitamin K supplements.

“People need to eat a healthy diet,” says Booth. “They need to eat their vegetables.”

Booth noted that the Tufts team works closely with Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, with the Rush team conducting observational studies in humans of brain health and cognition, while Tufts focuses on models to study specific mechanisms.

“We know that a healthy diet works, and that people who don’t eat a healthy diet don’t live as long or do as well cognitively,” says Booth.

“By choreographing animal and human studies together, we can do a better job of improving brain health long-term by identifying and targeting specific mechanisms.”

About this diet and brain aging research news

Author: Julie Rafferty

Source: Tufts University

Contact: Julie Rafferty – Tufts University

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Low Vitamin K Intake Impairs Cognition, Neurogenesis, and Elevates Neuroinflammation in C57BL/6 Mice” by Tong Zheng et al. Journal of Nutrition

Abstract

Low Vitamin K Intake Impairs Cognition, Neurogenesis, and Elevates Neuroinflammation in C57BL/6 Mice

Background

In addition to its important roles in blood coagulation and bone formation, vitamin K (VK) contributes to brain function. Low dietary VK intake, which is common among older adults, is associated with age-related cognitive impairment.

Objectives

To elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying VK’s effects on cognition, we investigated the effects of low VK (LVK) intake on cognition in C57BL/6 mice.

Methods

Male and female 9-mo-old C57BL/6 mice (n = 60) were fed an LVK diet or a control diet for 6 mo. Behavioral tests were performed on a subset of mice (n = 26) at 15 mo, and brain tissues were collected for follow-up analyses.

Results

Menaquinone-4, the predominant VK form in the brain, was significantly lower in LVK mice compared to controls (15.6 ± 13.3 compared with 189 ± 186 pmol/g, respectively, P < 0.01). LVK mice showed reduced recognition memory in the novel object test by spending a lower percentage of time exploring the novel object compared to controls (47.45% ± 4.17 compared with 58.08% ± 3.03, P = 0.04).

They also spent a significantly longer time learning the task of locating the platform in the Morris water maze test.

Within the hippocampal dentate gyrus, LVK mice had a significantly lower number of proliferating cells and fewer newly generated immature neurons compared to control mice. Additionally, more activated microglia cells were identified in the LVK mice.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that LVK intake reduced menaquinone-4 concentrations in brain tissues and impaired learning- and memory-related cognitive function. This impairment may be related to the observed reduced hippocampal neurogenesis and elevated neural inflammation.