A hormone implicated in monogamy and aggression in animals also promotes trust and cooperation in humans in risky situations, Caltech researchers say.

The findings, published the week of February 8 in the online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could prove useful for helping groups cooperate beneficially.

Research in rodents shows the hormone arginine vasopressin (AVP) promotes monogamous pair bonding and parental behavior, but also aggression in males. “Part of the dark side of monogamy is that an AVP-pumped-up male is more likely to behave aggressively toward intruders,” says study coauthor Colin Camerer, the Robert Kirby Professor of Behavioral Economics at Caltech.

In the new study, Camerer and his team tested the hypothesis that AVP might also play a role in social bonding in people and could help explain our species’ cooperative tendencies. “One of the reasons humans rule the world rather than apes is that we do things that require a great deal of trust. We cooperate in large-scale groups,” Camerer says. “Where does that come from? Is it something like pair bonding but just scaled up? And if it is, what role does AVP play?”

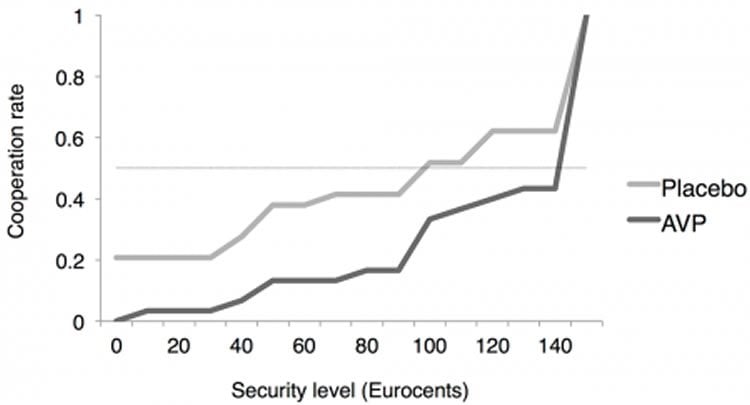

To investigate these questions, Camerer and his colleagues administered a nasal spray containing AVP or a hormone-free nasal spray (a placebo) to 59 male volunteers, aged 19 to 32 years old. Pairs of subjects then used computers to play a so-called assurance game in which they had to choose whether or not to cooperate with another player; “assurance” comes from the fact that subjects will take a risky action if they are sufficiently assured that others will, too. When they cooperated, both players received more points than they would have if they did not mutually cooperate. If one player chose not to cooperate but his partner made the opposite decision, the non-cooperative player received an intermediate payoff whereas the cooperative player received nothing.

“The game is designed to mimic situations in which people are willing to help, but only if everyone else helps too,” Camerer says. “Think of pitching in on a team project, or of a group of soldiers rushing the enemy. If a critical mass cooperates, then everyone else should go along. Thus it is in your best interest to help only if enough others do.”

To help ensure the players were engaged, the points they accumulated were converted into actual money at the end of the game (usually around $20).

The experiment showed that players who received AVP before the game were significantly more likely to cooperate than those who received the placebo. “By targeting a specific hormonal system in the human brain, we could manipulate people’s willingness to cooperate and help them do better,” says Gideon Nave, a graduate student in Camerer’s lab and a coauthor on the study.

Using control experiments, the researchers were also able to rule out other explanations for why the subjects were cooperating. For example, one possibility is that AVP was increasing the subjects’ appetite for risks. Alternatively, the administered hormone might be amplifying their altruistic tendencies, so that they just wanted to help other people regardless of the risk to themselves.

“We found that when we asked them, ‘Do you want to just give some money to this stranger?’ they don’t do it,” Camerer says. “So AVP seems to be quite specialized to this particular type of risky cooperation.”

To better understand the neural mechanism underlying AVP’s effect on risky cooperation, the researchers conducted the same experiment but this time had subjects—a separate group of 34 men, play the game while their brains were being imaged using a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner. The scans indicated that after AVP administration, a part of the brain’s reward system known as the ventral pallidum, a region that is known to have an abundance of AVP receptors—showed a change in neural activity when the players decided to cooperate.

“That was very encouraging, because it showed that the hormone is activating a part of the brain that is known to be rich in AVP receptors,” Camerer says.

Could the discovery that AVP increases the likelihood of risky cooperation have practical applications and be used, for example, to engender trust and foster cooperation in groups? Perhaps.

“You could imagine a high-stakes situation, such as a military operation, in which people have to trust each other to all do something difficult and it fails if anyone chickens out,” Camerer says. “In that case, you might want to administer AVP to help ensure that everyone is cooperative.”

In addition to Camerer and Nave, other coauthors on the paper, “Vasopressin increases human risky cooperative behavior,” include Claudia Brunnlieb, Stephan Schosser, and Bodo Vogt of the University of Magdeburg and Thomas Münte and Marcus Heldmann at the University of Lübeck in Germany.

Funding: The research was funded by a special grant of the Center for Behavioral Brain Sciences and by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Source: Ker Than – CalTech

Image Source: Image is credited to G. Nave/Caltech.

Original Research: Abstract for “Vasopressin increases human risky cooperative behavior” by Claudia Brunnlieb, Gideon Nave, Colin F. Camerer, Stephan Schosser, Bodo Vogt, Thomas F. Münte, and Marcus Heldmann in PNAS. Published online February 8 2016 doi:10.1073/pnas.1518825113

Abstract

Vasopressin increases human risky cooperative behavior

The history of humankind is an epic of cooperation, which is ubiquitous across societies and increasing in scale. Much human cooperation occurs where it is risky to cooperate for mutual benefit because successful cooperation depends on a sufficient level of cooperation by others. Here we show that arginine vasopressin (AVP), a neuropeptide that mediates complex mammalian social behaviors such as pair bonding, social recognition and aggression causally increases humans’ willingness to engage in risky, mutually beneficial cooperation. In two double-blind experiments, male participants received either AVP or placebo intranasally and made decisions with financial consequences in the “Stag hunt” cooperation game. AVP increases humans’ willingness to cooperate. That increase is not due to an increase in the general willingness to bear risks or to altruistically help others. Using functional brain imaging, we show that, when subjects make the risky Stag choice, AVP down-regulates the BOLD signal in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), a risk-integration region, and increases the left dlPFC functional connectivity with the ventral pallidum, an AVP receptor-rich region previously associated with AVP-mediated social reward processing in mammals. These findings show a previously unidentified causal role for AVP in social approach behavior in humans, as established by animal research.

“Vasopressin increases human risky cooperative behavior” by Claudia Brunnlieb, Gideon Nave, Colin F. Camerer, Stephan Schosser, Bodo Vogt, Thomas F. Münte, and Marcus Heldmann in PNAS. Published online February 8 2016 doi:10.1073/pnas.1518825113