Summary: Researchers report people who experienced emotional abuse and neglect as children exhibited increased amygdala activity in anticipation of a mild electrical shock. The findings suggest early life stress could have an impact on the perception of distant threat.

Source: SfN.

Neural activity associated with defensive responses in humans shifts between two brain regions depending on the proximity of a threat, suggests neuroimaging data from two independent samples of adults in the Netherlands published in The Journal of Neuroscience. In one sample, the findings suggest that emotional abuse during childhood may shift the balance of activity between these regions.

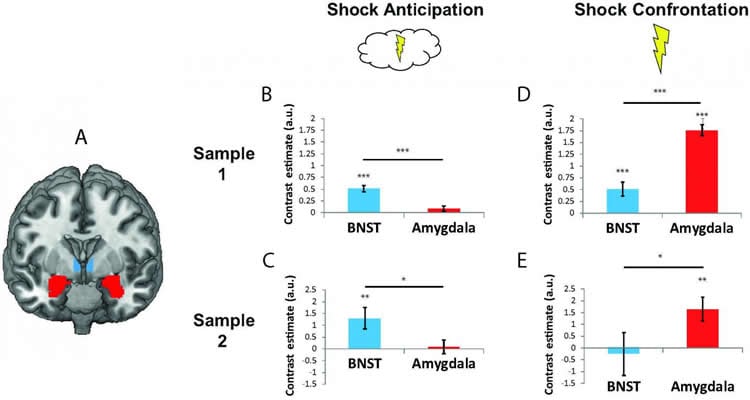

The amygdala and a closely related region called the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) are both activated in response to a threat, but it is unclear how these regions orchestrate defensive responses in humans. Floris Klumpers and colleagues found that anticipation of an uncomfortable but harmless electrical shock was associated with increased activity in BNST, which is strongly connected with other brain regions that may be involved in deciding how to respond to a distant threat. In contrast, the shock itself was associated with increased activity in the amygdala, which maintains stronger connections with lower brain regions that may facilitate immediate and involuntary responses to acute danger, such as increased heart rate.

Finally, the authors found that participants in one sample who reported greater childhood maltreatment (primarily emotional abuse and neglect rather than physical and sexual abuse) exhibited increased amygdala activity during shock anticipation. This finding shows how early life stress may impact an individual’s perception of distant threats.

Source: David Barnstone – SfN

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Klumpers et al., The Journal of Neuroscience (2017).

Original Research: Abstract for “How human amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis may drive distinct defensive responses” by Floris Klumpers, Marijn C. W. Kroes, Johanna Baas and Guillén Fernández in Journal of Neuroscience. Published online September 11 2017 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3830-16.2017

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]SfN “Childhood Maltreatment May Change Brain’s Response to Threat.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 11 September 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/threat-maltreatment-kids-7461/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]SfN (2017, September 11). Childhood Maltreatment May Change Brain’s Response to Threat. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved September 11, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/threat-maltreatment-kids-7461/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]SfN “Childhood Maltreatment May Change Brain’s Response to Threat.” https://neurosciencenews.com/threat-maltreatment-kids-7461/ (accessed September 11, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

How human amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis may drive distinct defensive responses

The ability to adaptively regulate responses to the proximity of potential danger is critical to survival and imbalance in this system may contribute to psychopathology. The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) is implicated in defensive responding during uncertain threat anticipation whereas the amygdala may drive responding upon more acute danger. This functional dissociation between the BNST and amygdala is however controversial, and human evidence scarce. Here we utilized data from two independent functional magnetic resonance imaging studies (N=108 males & N=70 (45 females)) to probe how coordination between the BNST and amygdala may regulate responses during shock anticipation and actual shock confrontation. In a subset of participants from sample 2 (N=48) we demonstrate that anticipation and confrontation evoke bradycardic and tachycardic responses respectively. Further, we show that in each sample when going from shock anticipation to the moment of shock confrontation neural activity shifted from a region anatomically consistent with the BNST towards the amygdala. Comparisons of functional connectivity during threat processing showed overlapping yet also consistently divergent functional connectivity profiles for the BNST and amygdala. Finally, childhood maltreatment levels predicted amygdala, but not BNST, hyperactivity during shock anticipation. Our results support an evolutionary conserved, defensive distance-dependent dynamic balance between BNST and amygdala activity. Shifts in this balance may enable shifts in defensive reactions via the demonstrated differential functional connectivity. Our results indicate that early life stress may tip the neural balance towards acute threat responding and via that route predispose for affective disorder.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

Previously proposed differential contributions of the BNST and amygdala to fear and anxiety have been recently debated. In spite of the significance of understanding their contributions to defensive reactions, there is a paucity of human studies that directly compared these regions on activity and connectivity during threat processing. We show strong evidence for a dissociable role of the BNST and amygdala in threat processing by demonstrating in two large participant samples that they show a distinct temporal signature of threat responding as well as a discriminable pattern of functional connections and differential sensitivity to early life threat.

“How human amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis may drive distinct defensive responses” by Floris Klumpers, Marijn C. W. Kroes, Johanna Baas and Guillén Fernández in Journal of Neuroscience. Published online September 11 2017 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3830-16.2017