Summary: Inadequate sleep can harm brain organization in early adolescence, researchers report. The disorganization can have an impact on cognitive processes, including attention, memory, emotional regulation, and controlling behaviors.

Source: Boston Children’s Hospital

We all know that if we don’t get enough sleep or don’t sleep well, we won’t be on top of our game the next day. And we know that many teens and preteens get too little or poor-quality sleep.

Now, a large, first-of-its kind study from Boston Children’s Hospital spells out in detail how inadequate sleep can jeopardize brain organization in early adolescence.

Findings appear in the journal Cerebral Cortex Communications.

“Early adolescence is a critical time in brain development,” says lead researcher Caterina Stamoulis, Ph.D., who directs the Computational Neuroscience Laboratory at Boston Children’s.

“Preteens’ brain circuits are rapidly maturing, particularly those supporting higher-level thought processes like decision-making, problem-solving, and the ability to process and integrate information from the outside world. We show that inadequate sleep could have enormous implications for cognitive and mental health for individual children and at the population level.”

Stamoulis, with research assistant Skylar Brooks and Eliot Katz, MD, a physician in Boston Children’s Sleep Center, analyzed sleep and brain imaging data from more than 5,500 early adolescents (ages 9 to 11 years). The data are from the long-running, NIH-funded Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study.

The sleep data were reported by parents on a 26-item survey with questions on sleep duration, sleep latency (time it typically takes the child to fall asleep), waking from sleep, difficulty falling back to sleep, difficulty breathing, snoring, nightmares, difficulty waking up, daytime sleepiness, and more.

The brain data came from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) performed at rest, independent of any task. From these data, the researchers identified multiple brain networks that play fundamental roles in cognitive function. They then examined the networks’ properties—which reflect how efficiently the brain processes information and how resilient its circuitry is to stressors—as a function of sleep quantity and quality.

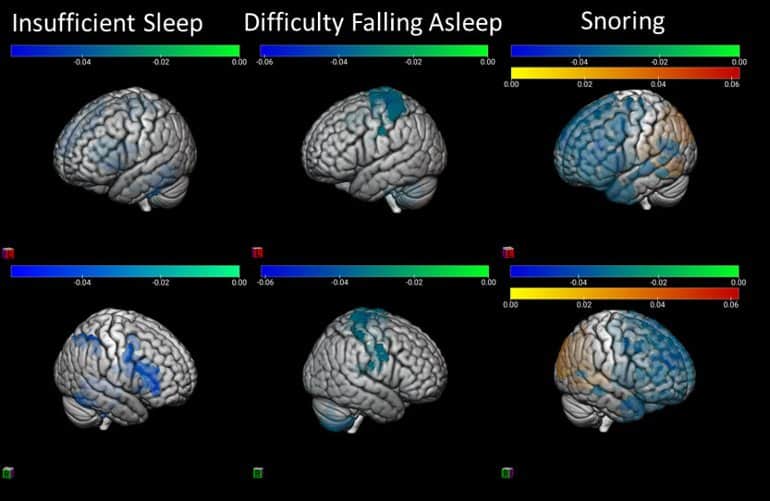

A rigorous computational analysis revealed that shorter sleep duration, longer sleep latency, frequent waking, and sleep-disordered breathing were associated with less efficient, flexible, and resilient brain networks. The researchers also observed abnormal network changes in specific parts of the brain: Multiple cortical areas as well as the thalamus, basal ganglia, hippocampus, and cerebellum.

The detrimental effects were widespread, from individual regions of the brain to large-scale circuits and the entire brain, and many appeared to be independent of unhealthy weight, which also negatively affected sleep quantity and quality.

“The network abnormalities we identified can potentially lead to deficits in multiple cognitive processes, including attention, reward, emotional regulation, memory, and the ability to plan, coordinate, and control actions and behaviors,” says Stamoulis.

The study also found racial disparities. Shorter sleep times and reduced sleep quality had disproportionate unhealthy effects on brain networks in non-white participants, who comprised about a third of the sample.

Additional findings on sleep:

- Girls slept less than boys, averaging 8 to 9 hours of sleep as compared with 9-11 hours for boys. They also took longer to fall asleep.

- Non-white children slept less than white children, averaging 8 to 9 hours versus 9 to 11 hours.

- Higher family income was significantly associated with longer sleep duration

- Longer screen time were significantly associated with shorter sleep duration

- Being overweight was associated with shorter sleep duration, more movement during the night, sweating, snoring, difficulty waking, and daytime sleepiness.

About this sleep and neurodevelopment research news

Author: Press Office

Source: Boston Children’s Hospital

Contact: Press Office – Boston Children’s Hospital

Image: The image is credited to Skylar Brooks and Caterina Stamoulis, Boston Children’s Hospital

Original Research: Open access.

“Shorter Duration and Lower Quality Sleep Have Widespread Detrimental Effects on Developing Functional Brain Networks in Early Adolescence” by Caterina Stamoulis et al. Cerebral Cortex Communications

Abstract

Shorter Duration and Lower Quality Sleep Have Widespread Detrimental Effects on Developing Functional Brain Networks in Early Adolescence

Sleep is critical for cognitive health, especially during complex developmental periods such as adolescence. However, its effects on maturating brain networks that support cognitive function are only partially understood.

We investigated the impact of shorter duration and reduced quality sleep, common stressors during development, on functional network properties in early adolescence—a period of significant neural maturation, using resting-state fMRI from 5566 children (median age = 120.0 months; 52.1% females) in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) cohort. Decreased sleep duration, increased sleep latency, frequent waking up at night, and sleep-disordered breathing symptoms were associated with lower topological efficiency, flexibility, and robustness of visual, sensorimotor, attention, fronto-parietal control, default-mode and/or limbic networks, and with aberrant changes in the thalamus, basal ganglia, hippocampus and cerebellum (p < 0.05).

These widespread effects, many of which were BMI-independent, suggest that unhealthy sleep in early adolescence may impair neural information processing and integration across incompletely developed networks, potentially leading to deficits in their cognitive correlates, including attention, reward, emotion processing and regulation, memory, and executive control.

Shorter sleep duration, frequent snoring, difficulty waking up and daytime sleepiness had additional detrimental network effects in non-white participants, indicating racial disparities in the influence of sleep metrics.