Summary: Greater exposure to screen time during infancy was linked to poor self-regulation and brain immaturity at age eight.

Source: Agency for Science, Technology, and Research

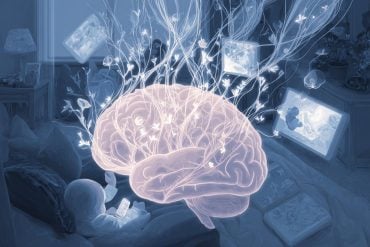

More children are now exposed to mobile digital devices at a young age as an avenue for entertainment and distraction.

A longitudinal cohort study in Singapore has confirmed that excessive screen time during infancy is linked to detrimental outcomes in cognitive functions, which continue to be apparent after eight years of age.

The research team looked at data from 506 children who enrolled in the Growing Up in Singapore towards Healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) cohort study since birth.

When the children were 12 months of age, parents were asked to report the average amount of screen time consumed on weekdays and weekends each week. Children were then classified into four groups based on screen time per day – less than one hour, one to two hours, two to four hours and more than four hours. At 18 months of age, brain activity was also collected using electroencephalography (EEG), a highly sensitive tool which tracks changes in brain activity.

Besides undergoing EEG, each child participated in various cognitive ability tests that measured his or her attention span and executive functioning (sometimes referred to as self-regulation skills) at the age of nine years.

The team first examined the association between screen time and EEG brain activity. The EEG readings revealed that infants who were exposed to longer screen time had greater “low-frequency” waves, a state that correlated with lack of cognitive alertness.

To find out whether screen time and the changes observed in the brain activity have any adverse outcomes during later childhood, the research team analysed all the data across three points for the same children – at 12 months, 18 months and nine years. As the duration of screen time increased, the greater the altered brain activity and more cognitive deficits were measured.

Children with executive function deficits often have difficulty controlling impulses or emotions, sustaining attention, following through multi-step instructions, and persisting in a hard task.

The brain of a child grows rapidly from the time of birth until early childhood. However, the part of the brain that controls executive functioning, or the prefrontal cortex, has a more protracted development.

Executive functions include the ability to sustain attention, process information and regulate emotional states, all of which are essential for learning and school performance. The advantage of this slower growth in the prefrontal cortex is that the imbuing and shaping of executive function skills can happen across the school years until higher education.

However, this same area of the brain responsible for executive functioning skills is also highly vulnerable to environmental influences over an extended period of time.

This study points to excessive screen time as one of the environmental influences that may interfere with executive function development. Prior research suggests that infants have trouble processing information on a two-dimensional screen.

When watching a screen, the infant is bombarded with a stream of fast-paced movements, ongoing blinking lights and scene changes, which require ample cognitive resources to make sense of and process. The brain becomes “overwhelmed” and is unable to leave adequate resources for itself to mature in cognitive skills such as executive functions.

Researchers are also concerned that families which allow very young children to have hours of screen time often face additional challenges. These include stressors such as food or housing insecurity, and parental mood problems. More work needs to be done to understand reasons behind excessive screen time in young children.

Further efforts are necessary to distinguish the direct association of infant screen use versus family factors that predispose early screen use on executive function impairments.

The study was a collaborative effort comprising researchers from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS Medicine), A*STAR’s Singapore Institute for Clinical Sciences (SICS), National Institute of Education, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, McGill University and Harvard Medical School. It was published in JAMA Pediatrics on 31 January 2023.

Lead author, Dr Evelyn Law from NUS Medicine and SICS’s Translational Neuroscience Programme, said, “The study provides compelling evidence to existing studies that our children’s screen time needs to be closely monitored, particularly during early brain development.” Dr Law is also a Consultant in the Division of Development and Behavioural Paediatrics at the Khoo Teck Puat – National University Children’s Medical Institute, National University Hospital.

Professor Chong Yap Seng, Dean of NUS Medicine and Chief Clinical Officer, SICS, added, “These findings from the GUSTO study should not be taken lightly because they have an impact on the potential development of future generations and human capital.

“With these results, we are one step closer towards better understanding how environmental influences can affect the health and development of children. This would allow us to make more informed decisions in improving the health and potential of every Singaporean by giving every child the best start in life.”

Professor Michael Meaney, Programme Director of the Translational Neuroscience Programme at SICS said, “In a country like Singapore, where parents work long hours and kids are exposed to frequent screen viewing, it’s important to study and understand the impact of screen time on children’s developing brains.”

About this technology and brain development research news

Author: Sharmaine Loh

Source: Agency for Science, Technology and Research

Contact: Sharmaine Loh – Agency for Science, Technology and Research

Image: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Open access.

“Associations Between Infant Screen Use, Electroencephalography Markers, and Cognitive Outcomes” by Evelyn Law et al. JAMA Pediatrics

Abstract

Associations Between Infant Screen Use, Electroencephalography Markers, and Cognitive Outcomes

Importance

Research evidence is mounting for the association between infant screen use and negative cognitive outcomes related to attention and executive functions. The nature, timing, and persistence of screen time exposure on neural functions are currently unknown. Electroencephalography (EEG) permits elucidation of the neural correlates associated with cognitive impairments.

Objective

To examine the associations between infant screen time, EEG markers, and school-age cognitive outcomes using mediation analysis with structural equation modeling.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective maternal-child dyad cohort study included participants from the population-based study Growing Up in Singapore Toward Healthy Outcomes (GUSTO). Pregnant mothers were enrolled in their first trimester from June 2009 through December 2010. A subset of children who completed neurodevelopmental visits at ages 12 months and 9 years had EEG performed at age 18 months. Data were reported from 3 time points at ages 12 months, 18 months, and 9 years. Mediation analyses were used to investigate how neural correlates were involved in the paths from infant screen time to the latent construct of attention and executive functioning. Data for this study were collected from November 2010 to March 2020 and were analyzed between October 2021 and May 2022.

Exposures

Parent-reported screen time at age 12 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Power spectral density from EEG was collected at age 18 months. Child attention and executive functions were measured with teacher-reported questionnaires and objective laboratory-based tasks at age 9 years.

Results

In this sample of 437 children, the mean (SD) age at follow-up was 8.84 (0.07) years, and 227 children (51.9%) were male. The mean (SD) amount of daily screen time at age 12 months was 2.01 (1.86) hours. Screen time at age 12 months contributed to multiple 9-year attention and executive functioning measures (η2, 0.03-0.16; Cohen d, 0.35-0.87). A subset of 157 children had EEG performed at age 18 months; EEG relative theta power and theta/beta ratio at the frontocentral and parietal regions showed a graded correlation with 12-month screen use (r = 0.35-0.37). In the structural equation model accounting for household income, frontocentral and parietal theta/beta ratios partially mediated the association between infant screen time and executive functioning at school age (exposure-mediator β, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.59; mediator-outcome β, −0.38; 95% CI, −0.64 to −0.11), forming an indirect path that accounted for 39.4% of the association.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, infant screen use was associated with altered cortical EEG activity before age 2 years; the identified EEG markers mediated the association between infant screen time and executive functions. Further efforts are urgently needed to distinguish the direct association of infant screen use compared with family factors that predispose early screen use on executive function impairments.