Psychology researchers recently found that practicing memory recall lead to improved long-term retention of science information when compared to other learning techniques.

The researchers compared students that learned by using concept maps versus a second group that practiced retrieval. They found the students who practiced retrieval to perform better in long-term retention tests.

This learning and memory research could help improve science teaching methods and lead to new strategies to teach science more effectively.

Read the release below for a more detailed explanation.

Science Learning Easier When Students Put Down Textbooks and Actively Recall Information

Actively recalling information from memory beats elaborate study methods

Put down those science text books and work at recalling information from memory. That’s the shorthand take away message of new research from Purdue University that says practicing memory retrieval boosts science learning far better than elaborate study methods.

“Our view is that learning is not about studying or getting knowledge ‘in memory,'” said Purdue psychology professor Jeffrey Karpicke, the lead investigator for the study that appears today in the journal Science. “Learning is about retrieving. So it is important to make retrieval practice an integral part of the learning process.”

Educators traditionally rely on learning activities that encourage elaborate study routines and techniques focused on improving the encoding of information into memory. But, when students practice retrieval, they set aside the material they are trying to learn and instead practice calling it to mind.

The study, “Retrieval Practice Produces More Learning Than Elaborative Studying With Concept Mapping,” tested both learning strategies alongside each other. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation’s Division of Undergraduate Education.

“In prior research, we established that practicing retrieval is a powerful way to improve learning,” said Karpicke. “Here we put retrieval practice to the test by comparing its effectiveness to an elaborative study method, specifically elaborative studying by creating concept maps.”

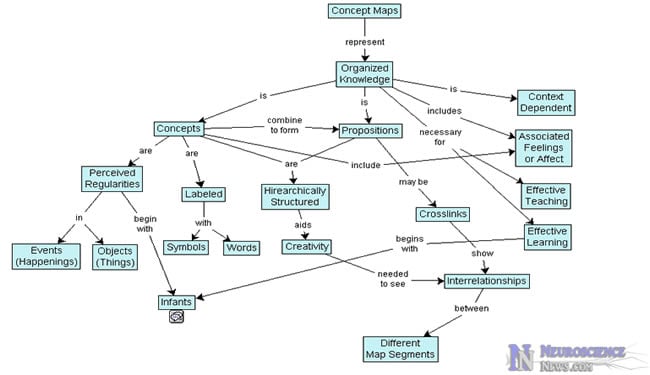

Concept mapping requires students to construct a diagram–typically using nodes or bubbles–that shows relationships among ideas, characteristics or materials. These concepts are then written down as a way of encoding them in a person’s memory.

The researchers say the practice is used extensively for learning about concepts in sciences such as biology, chemistry or physics.

In two studies, reported by Karpicke and his colleague, Purdue University psychology student Janell Blunt, a total of 200 students studied texts on topics from different science disciplines. One group engaged in elaborative study using concept maps while a second group practiced retrieval; they read the texts, then put them away and practiced freely recalling concepts from the text.

After an initial study period, both groups recalled about the same amount of information. But when the students returned to the lab a week later to assess their long-term learning, the group that studied by practicing retrieval showed a 50 percent improvement in long-term retention above the group that studied by creating concept maps.

This, despite the students own predictions about how much they would actually remember. “Students do not always know what methods will produce the best learning,” said Karpicke in discussing whether students are good at judging the success of their study habits.

He found that when students have the material right in front of them, they think they know it better than they actually do. “It may be surprising to realize that there is such a disconnect between what students think will afford good learning and what is actually best. We, as educators, need to keep this in mind as we create learning tools and evaluate educational practices,” he said.

The researchers showed retrieval practice was superior to elaborative studying in all comparisons.

“The final retention test was one of the most important features of our study, because we asked questions that tapped into meaningful learning,” said Karpicke.

The students answered questions about the specific concepts they learned as well as inference questions asking them to draw connections between things that weren’t explicitly stated in the material. On both measures of meaningful learning, practicing retrieval continued to produce better learning than elaborative studying.

Karpicke says there’s nothing wrong with elaborative learning, but argues that a larger place needs to be found for retrieval practice. “Our challenge now is to find the most effective and feasible ways to use retrieval as a learning activity–but we know that it is indeed a powerful way to enhance conceptual learning about science.”

Notes about the research

Media Contacts:

Bobbie Mixon, NSF

Amy Patterson Neubert, Purdue News Service

Principal Investigators:

Jeffery Karpicke, Purdue University

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency that supports fundamental research and education across all fields of science and engineering. In fiscal year (FY) 2010, its budget is about $6.9 billion. NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives over 45,000 competitive requests for funding, and makes over 11,500 new funding awards. NSF also awards over $400 million in professional and service contracts yearly.

Source: NSF News