Summary: Why are some people naturally resistant to weight gain while others struggle with lifelong obesity? Researchers have discovered a “molecular switch” in the developing brain that may hold the answer. The study identifies a transcription factor called Otp that determines the fate of immature neurons in the hypothalamus.

These cells are at a crossroads: they can either become appetite-suppressing (POMC) neurons or appetite-stimulating (AgRP) neurons. By uncovering how the brain establishes these “metabolic set points” during early development, scientists have found that disabling this switch can actually shield the brain from overreacting to high-fat diets, potentially preventing obesity before it even starts.

Key Facts

- The “Otp” Switch: The protein Otp acts as a traffic controller, directing precursor cells to become either “hunger” or “fullness” neurons.

- AgRP vs. POMC: The switch primarily steers cells toward becoming AgRP neurons, which trigger intense hunger—an evolutionary adaptation meant to help ancestors survive food scarcity.

- Maladaptive Evolution: In a world of calorie-dense food, this survival switch now amplifies vulnerability to obesity by encouraging overeating.

- Resistance to Obesity: When researchers disabled the Otp switch in preclinical models, the subjects failed to develop the “hunger” neurons and were significantly more resistant to weight gain, even on high-fat diets.

- Female Vulnerability: The study noted that the protective effect of disabling this switch was particularly strong in females, linked to enhanced estrogen receptor signaling.

Source: UT Southwestern

Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have discovered that a crucial developmental process in the brain’s hypothalamus may influence how susceptible individuals are to obesity.

Their preclinical findings, published in Neuron, show that a transcription factor called Otp acts as a molecular “switch” that directs immature hypothalamic neurons toward either appetite-suppressing or appetite-stimulating fates – their ultimate identities as specialized cells. The researchers found that disrupting this switch alters feeding behavior and protects mice from diet-induced obesity.

“These findings show that early developmental decisions in the hypothalamus have a long-lasting impact on energy balance,” said senior author Chen Liu, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Internal Medicine and Neuroscience and an Investigator in the Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute at UT Southwestern.

“By uncovering this fate-switching program, we can begin to understand how the brain establishes lifelong metabolic set points.”

The hypothalamic melanocortin system – comprising pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons that promote satiety (the feeling of fullness after eating) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons that trigger hunger – is essential for maintaining energy balance. Although these neurons have been well-studied in adults, how they arise during early development has remained unclear.

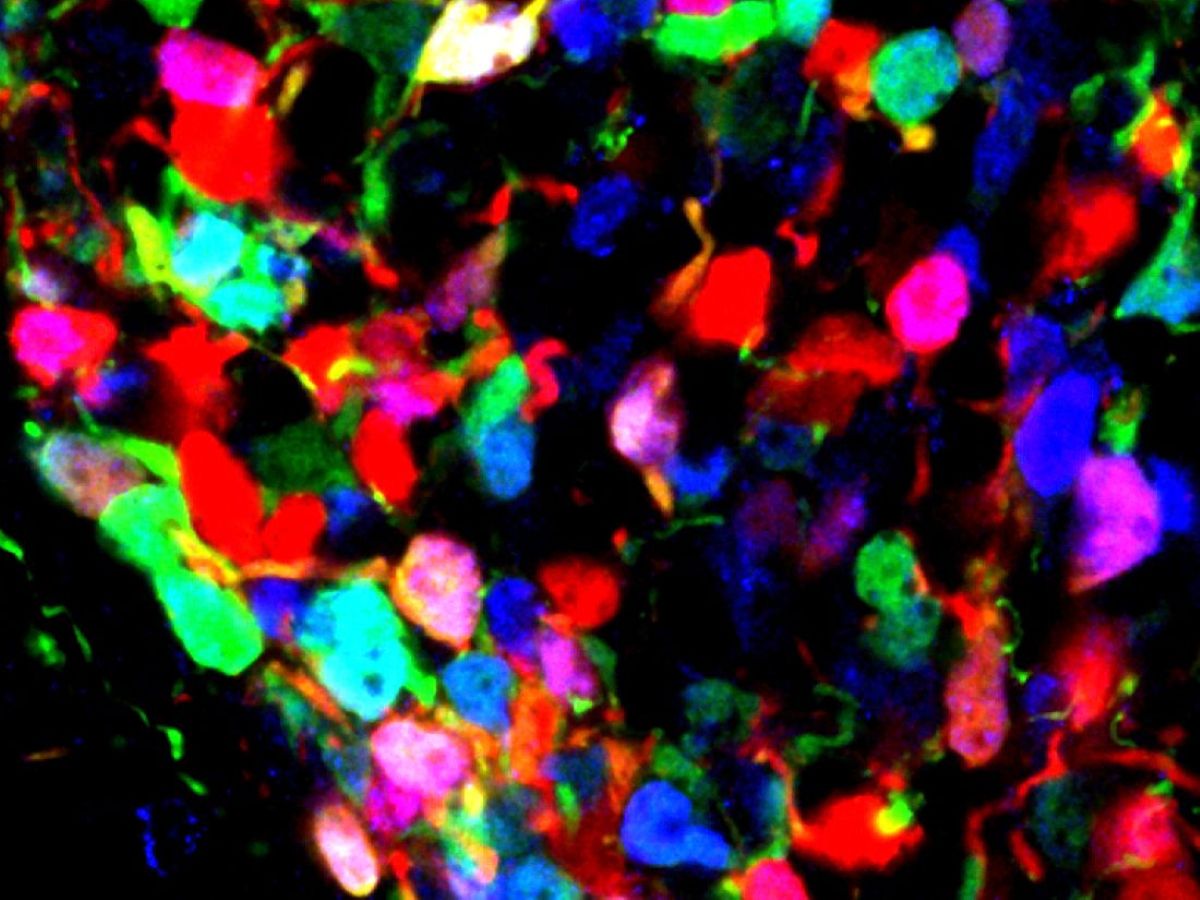

Using state-of-the-art, single-nucleus multiome sequencing, Dr. Liu and his colleagues in the Liu Lab mapped the full landscape of neurons derived from POMC-expressing precursor (parent) cells in the adult mouse hypothalamus.

The researchers found that fewer than one-third of these precursor neurons continue to express POMC in adulthood. Instead, POMC precursors diversify into many neuronal subtypes, including a substantial portion of adult AgRP neurons.

The study identifies Otp as a key regulator guiding POMC-derived neurons toward AgRP identities. When Otp was selectively deleted in POMC-expressing precursors, these cells failed to acquire the AgRP hunger-triggering fate and instead retained alternative POMC satiety-promoting neuron identities.

As a result, adult mice lacking this developmental switch showed reduced urges to consume high-fat diets and were resistant to diet-induced obesity. Notably, this protective effect was stronger in females, due in part to enhanced estrogen receptor (ERα) signaling in specific POMC-derived subpopulations.

“From an evolutionary standpoint, the POMC→AgRP fate switch likely served as an adaptive mechanism,” said Dr. Liu, a Principal Investigator in UTSW’s Center for Hypothalamic Research.

“In environments where food availability fluctuated, animals needed a rapid, robust way to increase food intake when high-calorie food became available. By generating a population of highly responsive ‘hunger’ neurons, this developmental switch enabled overeating, helping animals build energy reserves and survive periods of scarcity.”

In today’s world, however, where calorie-dense foods are more readily accessible, this once-beneficial mechanism can amplify vulnerability to obesity, Dr. Liu said. The team’s findings demonstrate that disabling this switch during early development shields the brain from overreacting to high-fat diets, ultimately lowering obesity risk. He said this contrast highlights a broader theme in modern metabolic disease: Biological programs tuned for ancestral survival can become maladaptive in contemporary environments.

Dr. Liu said he and his colleagues plan to investigate next whether external factors, such as maternal overnutrition or undernutrition, influence this genetic fate-switch program and thereby affect metabolic health later in life.

Other UTSW researchers who contributed to this study are co-first authors Baijie Xu, Ph.D., postdoctoral researcher in the Liu Lab, and Li Li, Ph.D., former Instructor of Internal Medicine, former postdoctoral research fellow in the Liu Lab, and current Assistant Professor of Zoology and Physiology at the University of Wyoming; Swati, M.S., Research Associate, Lab Manager in the Liu Lab; Rong Wan, M.S., Research Associate in the Liu Lab; Amanda Almeida, M.B.A., Director of Ambulatory Analytics; and Steven Wyler, Ph.D., Instructor of Internal Medicine and a member of the Center for Hypothalamic Research.

Funding: This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK114036, DK130892, and DK136592); a postdoctoral fellowship (23POST1019715) and a Career Development Award (24CDA1257999) from the American Heart Association; and the UTSW Metabolic Phenotyping Core, which was supported by a UTSW Nutrition & Obesity Research Center (NORC) grant (P30DK127984).

Key Questions Answered:

A: Largely, yes. This study shows that the ratio of hunger-stimulating to fullness-promoting neurons is decided during early development. Your brain’s “baseline” for how much you want to eat is established by this genetic switch.

A: Currently, the research focuses on how this switch works during development. However, identifying the Otp protein provides a specific target. Future therapies might look for ways to influence these pathways to “reset” a person’s metabolic set point.

A: The researchers found that the lack of this “hunger switch” interacted with estrogen receptors, making the protective effect against obesity even more pronounced in females. This highlights how sex hormones and brain development work together to manage weight.

Editorial Notes:

- This article was edited by a Neuroscience News editor.

- Journal paper reviewed in full.

- Additional context added by our staff.

About this neurodevelopment and obesity research news

Author: Media Relations

Source: UT Southwestern

Contact: Media Relations – UT Southwestern

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Developmental reprogramming in melanocortin neurons modulates diet-induced obesity in mice” by Baijie Xu, Li Li, Meilin Chen, Zan Wu, Xiameng Chen, Swati, Rong Wan, Amanda G. Almeida, Steven C. Wyler, and Chen Liu. Neuron

DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2025.12.022

Abstract

Developmental reprogramming in melanocortin neurons modulates diet-induced obesity in mice

Central melanocortin neurons are essential regulators of energy balance in mammals. Specifically, hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons promote satiety, while agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons drive hunger.

Despite their well-understood roles in adulthood, the developmental processes that shape this system remain poorly understood.

Pomc-expressing precursors give rise to multiple neuronal subtypes, including a subset of adult AgRP neurons, but the precise mechanisms guiding these fate transitions—and their lasting impact on metabolic health—have remained unknown. Here, we show that the transcription factor Otp directs a developmental fate switch between POMC and AgRP neuron identities.

Loss of Otp in Pomc-expressing precursors disrupts this switch, altering the balance of anorexigenic and orexigenic neurons in the adult hypothalamus. This developmental event is critical for programming susceptibility to diet-induced obesity in mice.

Our findings highlight the remarkable plasticity within the developing melanocortin system and underscore the importance of using refined genetic tools to target these neurons more precisely.