Summary: For the first time, scientists can record the full “electrical dialogue” occurring across an entire lab-grown human organoid. While these “mini-brains” are powerful tools for studying development and disease, previous technology could only sample a tiny fraction of their activity using flat, rigid sensors.

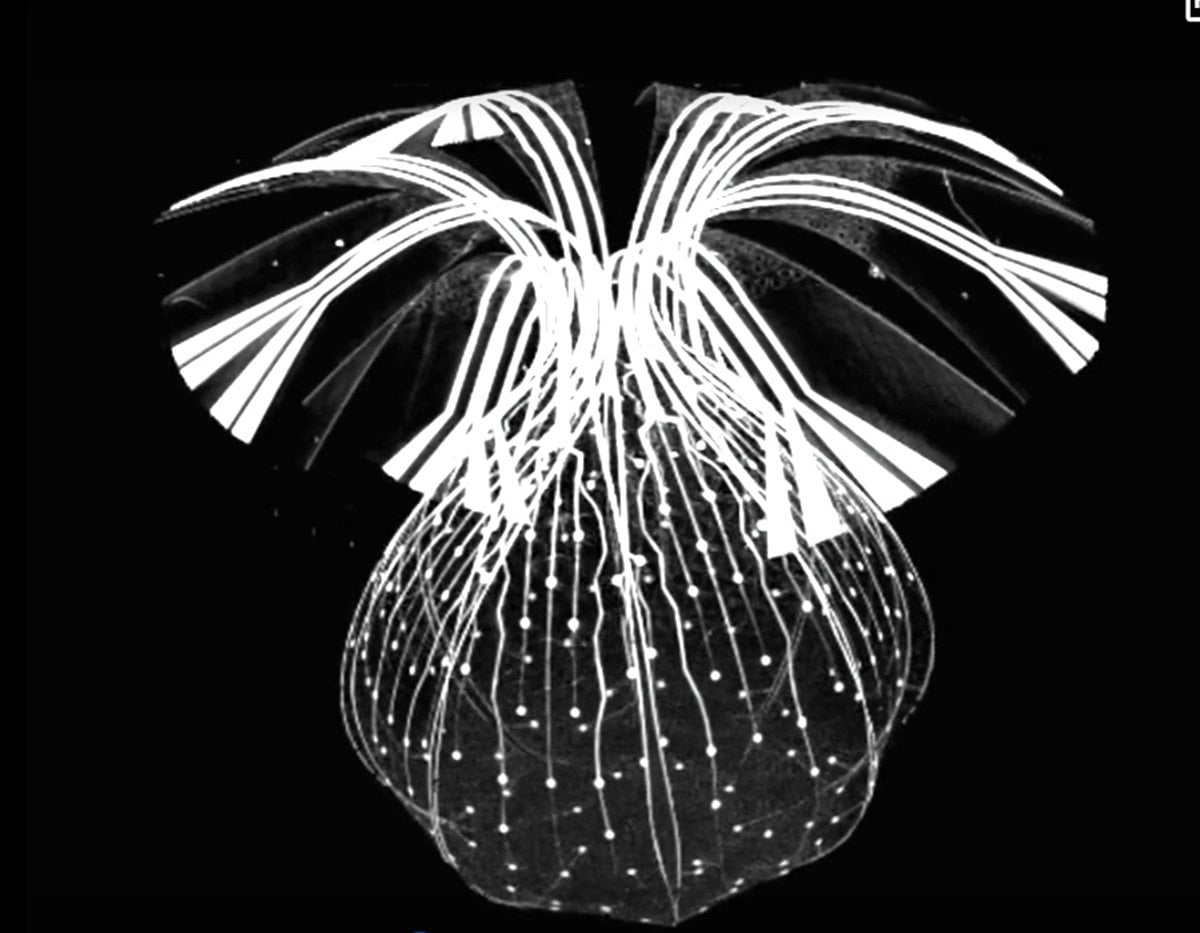

A new study reveals a breakthrough: a soft, 3D bioelectronic framework that “pops up” to envelope the organoid like a high-tech mesh. With hundreds of miniaturized electrodes, this device captures synchronized rhythms spanning the entire tissue, allowing researchers to see how neural networks communicate, respond to drugs, and even grow into specific shapes.

Key Facts

- Full-Network Mapping: The device covers over 90% of the organoid’s surface, moving beyond localized probing to capture coordinated, whole-tissue neural rhythms.

- The “Pop-Up” Mechanism: Using mechanical buckling similar to a 3D pop-up book, the device transforms from a flat lattice into a spherical cage that gently hugs the tissue.

- Miniaturized Precision: The array features 240 electrodes, each only 10 microns in diameter—roughly the size of an individual human cell.

- Breathable Bioelectronics: The mesh is porous, allowing the living tissue to “breathe” by letting oxygen and nutrients in while waste products flow out.

- Growth Engineering: Beyond recording, the framework can be engineered into cubes or hexagons, forcing the organoids to grow into specific shapes for potential “stacking” in future multi-organ models.

Source: Northwestern University

A team led by Northwestern University and Shirley Ryan AbilityLab scientists have developed a new technology that can eavesdrop on the hidden electrical dialogues unfolding inside miniature, lab-grown human brain-like tissues.

Known as human neural organoids — and sometimes called “mini brains” — these millimeter-sized structures are powerful models of brain development and disease. But until now, scientists could only record and stimulate activity from a small fraction of their neurons — missing network-wide dynamics that give rise to coordinated rhythms, information processing and the complex patterns of activity that define brain function.

For the first time, the new technology overcomes that stubborn limitation. The soft, three-dimensional (3D) electronic framework wraps around an organoid like a breathable, high-tech mesh.

Rather than sampling select regions, it delivers near-complete, shape-conforming coverage with hundreds of miniaturized electrodes. That dense, three-dimensional interfacing enables scientists to map and manipulate neural activity across almost the entire organoid.

By moving from localized probing to true whole-network mapping, the work brings organoid research closer to capturing how real human brains develop, function and even fail.

The study was published today (Feb. 18) in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

“Human stem cell-derived organoids have become a major focus of biomedical research because they enable patient-specific studies of how tissues respond to drugs and emerging therapies,” said Northwestern bioelectronic pioneer John A. Rogers, who led the device development.

“Labs in academia and industry have developed these tissue constructs over the years, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has initiated funding streams to accelerate work in this direction. A key missing component is hardware technology that can interrogate, stimulate and manipulate these tiny analogs to organs in the human body.”

“This advance is really about building the right tools for a new class of biological models,” said Dr. Colin Franz, who led the organoid development.

“Human neural organoids are living 3D tissues that contain active neural circuits communicating through electrical signals. However, the state-of-the-art instruments we use to study them were originally designed for flat layers of cells and do not interface well with organoids that are spherical and three dimensional.

“By creating soft, shape-matched electronics that conform to the organoid’s geometry, we can now record from and stimulate hundreds of locations across its surface at once. This allows us to study neural activity at the level of whole networks rather than isolated signals.”

Rogers is the Louis Simpson and Kimberly Querrey Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Biomedical Engineering and Neurological Surgery at Northwestern, where he has appointments in the McCormick School of Engineering and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. He also directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics and the Querrey Simpson Institute for Translational Engineering for Advanced Medical Systems.

An expert in regenerative neuroscience, Franz is a physician-scientist at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab and an associate professor of physical medicine & rehabilitation, medicine (pulmonary and critical care) and neurology at Feinberg and an attending physician. Rogers and Franz co-led the study with Yihui Zhang of Tsinghua University in China and John Finan of the University of Illinois Chicago.

From fragments to full networks

Over the past decade, scientists have moved from flat dishes of neurons to self-organizing, 3D mini brains grown from human stem cells. These organoids can develop interconnected neural circuits and generate synchronized electrical rhythms reminiscent of early brain development.

“Human-derived, 3D tissue models like organoids are beginning to change how we study disease and develop treatments,” Franz said. “They also have the potential to reduce our reliance on animal models.”

Yet even as these organoids form intricate neural networks, researchers can hear only fragments of their electrical conversations. Because they are flat and rigid, existing recording technologies cannot conform to the brain’s natural curves and wrinkles. By sampling activity from a mere handful of sites on the organoid, researchers risk missing the coordinated activity that emerges across the entire structure.

“Integrated circuits in consumer electronics are perfectly planar, sitting on wafer-based substrates,” Rogers said. “That conventional layout represents a very significant geometrical mismatch relative to the spherical shapes of these organoids.”

A bioelectronic ‘pop-up book’

To overcome this limitation, the Northwestern team designed a soft, porous scaffold that begins as a flat, rubbery lattice and then transforms into a precisely engineered 3D shape. A controlled mechanical buckling drives the transformation — the same mechanism that causes flat paper to convert into 3D structures in a “pop-up” book.

This framework gently envelopes the organoid, matching its curvature. The mesh-like perforations allow oxygen and nutrients to flow into the organoid and carbon dioxide and waste products to flow out.

“The device’s structure needs to support these metabolic processes to sustain the viability of the tissue,” Rogers said. “Basically, the organoid needs to breathe. The hardware must not significantly constrain or suffocate it.”

One version of the device covered 91% of an organoid’s surface and incorporated 240 individually addressable microelectrodes. Because organoids are often just a millimeter in diameter, the engineers had to push the size of the electrodes to the extreme. They developed highly miniaturized electrodes, measuring just 10 microns in diameter — about the size of an individual cell.

When the team tested systems with only eight or 32 electrodes, they captured limited, localized signals. With the full 240-channel array, the team recorded synchronized oscillatory waves spanning the entire organoid. Because the researchers know each electrode’s exact position, they can create a 3D map of the organoid’s electrical activity.

Shaping and studying living neural systems

In experiments, the team watched signals spark in one region and ripple across the network. By revealing split-second delays between distant areas, the technology picked up clear signs of coordinated communication within the organoid’s neurons.

Beyond mapping neural activity in detail, the platform also proved sensitive to the effects of drugs. The team tested several compounds and observed clear, predictable changes in how the organoids’ networks fired. For example, exposure to 4-aminopyridine — a medication used to improve walking in people with multiple sclerosis — increased neural signaling.

But exposure to botulinum toxin, which blocks communication between nerve cells and is used to treat muscle spasticity, disrupted coordinated activity. These results show that the bioelectronic interface can detect meaningful drug responses in living human neural tissue models, demonstrating its potential as a powerful tool for testing therapies.

But the system doesn’t just listen — it also speaks. It can deliver tiny electrical pulses, triggering responses in specific regions. When combined with imaging and optogenetics, the system enables scientists to observe and influence neural activity.

The scientists also discovered that the device can shape how organoids grow. By modifying the microlattice design, the team engineered non-spherical geometries, including hexagonal and cubic shapes. Inside those frameworks, the organoids grew into matching shapes.

“With this ability, we can imagine assembling different types of organoids to create miniature versions of the human body,” Rogers said. “With cube-shaped organoids, we could stack them together like Lego blocks.”

What’s next

With more work, organoids could play a powerful role in the future of medicine. Because they are grown from human stem cells — even a patient’s own cells — organoids offer a way to model disease and test treatments in living, 3D neural networks. Researchers also could use them to study how brain disorders develop, evaluate drug responses and assess whether experimental regenerative strategies can restore lost, coordinated brain activity.

With tools that map activity across nearly the entire organoid, scientists can assess whether potential regenerative treatments truly rebuild functional circuits — a critical step toward developing effective therapies for brain disorders.

“As organoids become a growing priority for NIH initiatives and for industry drug development efforts, technologies like this will be essential for turning these sophisticated tissue models into practical platforms for understanding disease, testing therapies and advancing clinical neuroscience,” Franz said.

Funding: The study, “Shape-conformal porous frameworks for full coverage of neural organoids and high-resolution electrophysiology,” was supported by the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics, National Institutes of Health (award number R01NS113935), the National Science Foundation, the Belle Carnell Regenerative Neurorehabilitation Fund, the New Cornerstone Science Foundation and the Haythornthwaite Foundation Research Initiation Grant.

Key Questions Answered:

A: They aren’t conscious, but they do generate synchronized electrical pulses similar to those seen in the early stages of human brain development. This new mesh allows us to finally “hear” the full complexity of those pulses for the first time.

A: Standard organoids are spherical, which makes them hard to connect. By growing them into cubes using the mesh scaffold, scientists can imagine stacking them like LEGO blocks to create complex, multi-layered models of the human nervous system.

A: Because these organoids can be grown from a specific patient’s stem cells, doctors can use the electronic mesh to test how that patient’s actual brain tissue responds to different medications—all in a lab dish before a single pill is prescribed.

About this neurotech research news

Author: Amanda Morris

Source: Northwestern University

Contact: Amanda Morris – Northwestern University

Image: The image is credited to John A. Rogers/Northwestern University

Original Research: Open access.

“Shape-conformal porous frameworks for full coverage of neural organoids and high-resolution electrophysiology” by Naijia Liu, Shahrzad Shiravi, Tianqi Jin, Jiaqi Liu, Zhengguang Zhu, Jiying Li, Ingrid Cheung, Haohui Zhang, Yue Wang, Qingyuan Li, Zijie Xu, Liangsong Zeng, Maria Jose Quezada, Andres Villalobos, Yasaman Samei, Shreyaa Khanna, Shuozhen Bao, Mingzheng Wu, Sida Liang, Xu Cheng, Zengyao Lv, Woo-Youl Maeng, Yamin Zhang, Haiwen Luan, Stephen A. Boppart, Yonggang Huang, Yihui Zhang, Colin K. Franz, John D. Finan & John A. Rogers. Nature Biomedical Engineering

DOI:10.1038/s41551-026-01620-y

Abstract

Shape-conformal porous frameworks for full coverage of neural organoids and high-resolution electrophysiology

Human neural organoids are essential platforms for fundamental and applied research due partly to their complex, three-dimensional neuronal circuit geometries.

Standard and recently developed neural interface technologies have shortcomings in their ability to electrically characterize and control neural activity in these systems, owing to their limited accessibility to neuron populations and microelectrode densities.

Here we report a shape-matched, soft, three-dimensional mesoscale framework with nearly full surface coverage to neural organoids that supports high channel count interfaces for precision electrophysiology and programmed electrical stimulation.

The neural interface is designed via inverse modelling techniques and self-assembles three-dimensionally around the organoids.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of neural activities allows high-resolution spatial electrophysiology to reveal network-level characteristics in neural organoids.

The porous framework offers options for simultaneous fluorescence imaging, localized optogenetic neuromodulation, longitudinal monitoring, pharmacological evaluations and modelling of neural disease phenotypes, demonstrating broad applicability for studies of human-derived cortical and spinal organoids.