Summary: Researchers have been able to successfully boost the regeneration of mature nerve cells in the spinal cord of adult mice following spinal cord injury.

Source: UT Southwestern.

UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers successfully boosted the regeneration of mature nerve cells in the spinal cords of adult mammals – an achievement that could one day translate into improved therapies for patients with spinal cord injuries.

“This research lays the groundwork for regenerative medicine for spinal cord injuries. We have uncovered critical molecular and cellular checkpoints in a pathway involved in the regeneration process that may be manipulated to boost nerve cell regeneration after a spinal injury,” said senior author Dr. Chun-Li Zhang, Associate Professor of Molecular Biology at UT Southwestern.

Dr. Zhang cautioned that this research in mice, published today by Cell Reports, is still in the early experimental stage and is not ready for clinical translation.

“Spinal cord injuries can be fatal or cause severe disability. Many survivors experience paralysis, reduced quality of life, and enormous financial and emotional burdens,” said lead author Dr. Lei-Lei Wang, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Zhang’s lab whose series of in vivo (in a living animal) screens led to the findings.

Spinal cord injuries can lead to irreversible neural network damage that, combined with scarring, can ultimately impair motor and sensory functions. These outcomes arise because adult spinal cords have very limited ability to regenerate damaged neurons to aid in healing, said Dr. Zhang, a W.W. Caruth, Jr. Scholar in Biomedical Research and member of the Hamon Center for Regenerative Science and Medicine.

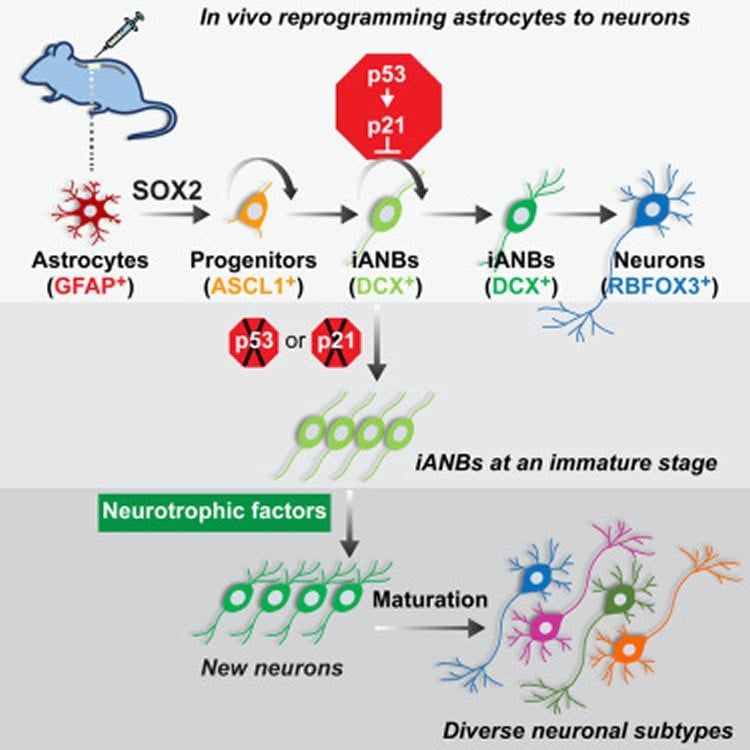

Dr. Zhang’s lab focuses on glial cells, the most abundant non-neuronal type of cells in the central nervous system. Glial cells support nerve cells in the spinal cord and form scar tissue in response to injury. In 2013 and 2014, the Zhang laboratory created new nerve cells in the brains and spinal cords of mice by introducing transcription factors that promoted the transition of adult glial cells into more primitive, stem cell-like states, and then coaxed them to mature into adult nerve cells.

The number of new spinal nerve cells generated by this process was low, however, leading researchers to focus on ways to amplify adult neuron production.

In a two-step process, researchers first silenced parts of the p53-p21 protein pathway that acts as a roadblock to the reprogramming of glial cells into the more primitive, stem-like types of cells with potential to become nerve cells. Although the blockade was successfully lifted, many cells failed to advance past the stem cell-like stage. In the second step, mice were screened for factors that could boost the number of stem-like cells that matured into adult neurons. They identified two growth factors – BDNF and Noggin – that accomplished this goal, Dr. Zhang said. Using this approach, researchers increased the number of newly matured neurons by tenfold.

“Silencing the p53-p21 pathway gave rise to progenitor (stem-like) cells, but only a few matured. When the two growth factors were added, the progenitors matured by the tens of thousands,” Dr. Zhang said.

Further experiments that looked for biomarkers commonly found in nerve cell communication indicated that the new neurons may form networks, he added.

“Because p53 activation is thought to safeguard cells from undergoing uncontrolled proliferation, as in cancer, we followed mice that had temporary inactivation of the p53 pathway for 15 months without observing any increased cancer risk in the spinal cord,” he said.

“Our ability to successfully produce a large population of long-lived and diverse subtypes of new neurons in the adult spinal cord provides a cellular basis for regeneration-based therapy for spinal cord injuries. If borne out by future studies, this strategy would pave the way for using a patient’s own glial cells, thereby avoiding transplants and the need for immunosuppressive therapy,” Dr. Zhang said.

Other UT Southwestern authors included postdoctoral researcher Dr. Wenjiao Tai and senior research scientist Yuhua Zou, both of Molecular Biology and the Hamon Center, as well as former UTSW visiting instructor Dr. Zhida Su, with the Institute of Neuroscience and the Second Military Medical University of Shanghai, China. A researcher from Indiana University School of Medicine also participated.

Funding: This research was funded by the Welch Foundation, the Decherd Foundation, the Mobility Foundation Center for Rehabilitation Research, the National Institutes of Health, the National Key Technologies Research and Development Program of China, and the Texas Institute for Brain Injury and Repair (TIBIR) at UT Southwestern. Founded in 2014, TIBIR embodies a comprehensive and transformative approach to how brain injuries are prevented and treated.

Source: Kathryn DeMott – UT Southwestern

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to credited to Zhang et al.Cell Reports.

Original Research: Full open access research for “The p53 Pathway Controls SOX2-Mediated Reprogramming in the Adult Mouse Spinal Cord” by Lei-Lei Wang, Zhida Su, Wenjiao Tai, Yuhua Zou, Xiao-Ming Xu, and Chun-Li Zhang in Cell Reports. Published online October 11 2016 doi:/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.038

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]UT Southwestern. “Amplifying Regeneration of Spinal Nerve Cells.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 12 October 2016.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/neurogenesis-spinal-neurons-5278/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]UT Southwestern. (2016, October 12). Amplifying Regeneration of Spinal Nerve Cells. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved October 12, 2016 from https://neurosciencenews.com/neurogenesis-spinal-neurons-5278/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]UT Southwestern. “Amplifying Regeneration of Spinal Nerve Cells.” https://neurosciencenews.com/neurogenesis-spinal-neurons-5278/ (accessed October 12, 2016).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

The p53 Pathway Controls SOX2-Mediated Reprogramming in the Adult Mouse Spinal Cord

Highlights

•In vivo screens examine reprogramming in the adult mouse spinal cord

•The p53 pathway controls cell-cycle exit of induced neuroblasts from astrocytes

•A neurotrophic milieu is required for efficient maturation of induced neuroblasts

•Induced neuroblasts mature into diverse but predominantly glutamatergic neurons

Summary

Although the adult mammalian spinal cord lacks intrinsic neurogenic capacity, glial cells can be reprogrammed in vivo to generate neurons after spinal cord injury (SCI). How this reprogramming process is molecularly regulated, however, is not clear. Through a series of in vivo screens, we show here that the p53-dependent pathway constitutes a critical checkpoint for SOX2-mediated reprogramming of resident glial cells in the adult mouse spinal cord. While it has no effect on the reprogramming efficiency, the p53 pathway promotes cell-cycle exit of SOX2-induced adult neuroblasts (iANBs). As such, silencing of either p53 or p21 markedly boosts the overall production of iANBs. A neurotrophic milieu supported by BDNF and NOG can robustly enhance maturation of these iANBs into diverse but predominantly glutamatergic neurons. Together, these findings have uncovered critical molecular and cellular checkpoints that may be manipulated to boost neuron regeneration after SCI.

“The p53 Pathway Controls SOX2-Mediated Reprogramming in the Adult Mouse Spinal Cord” by Lei-Lei Wang, Zhida Su, Wenjiao Tai, Yuhua Zou, Xiao-Ming Xu, and Chun-Li Zhang in Cell Reports. Published online October 11 2016 doi:/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.038