Scientists discover neural mechanisms in mouse brains that indicate that we actively forget as we learn.

They say that once you’ve learned to ride a bicycle, you never forget how to do it. But new research suggests that while learning, the brain is actively trying to forget. The study, by scientists at EMBL and University Pablo Olavide in Sevilla, Spain, is published today in Nature Communications.

“This is the first time that a pathway in the brain has been linked to forgetting, to actively erasing memories,” says Cornelius Gross, who led the work at EMBL.

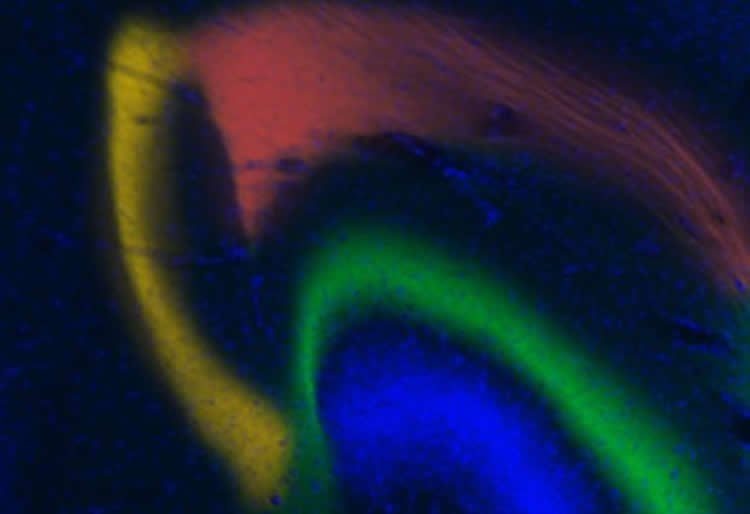

At the simplest level, learning involves making associations, and remembering them. Working with mice, Gross and colleagues studied the hippocampus, a region of the brain that’s long been known to help form memories. Information enters this part of the brain through three different routes. As memories are cemented, connections between neurons along the ‘main’ route become stronger.

When they blocked this main route, the scientists found that the mice were no longer capable of learning a Pavlovian response – associating a sound to a consequence, and anticipating that consequence. But if the mice had learned that association before the scientists stopped information flow in that main route, they could still retrieve that memory. This confirmed that this route is involved in forming memories, but isn’t essential for recalling those memories. The latter probably involves the second route into the hippocampus, the scientists surmise.

But blocking that main route had an unexpected consequence: the connections along it were weakened, meaning the memory was being erased.

“Simply blocking this pathway shouldn’t have an effect on its strength,” says Agnès Gruart from University Pablo Olavide. “When we investigated further, we discovered that activity in one of the other pathways was driving this weakening.”

Interestingly, this active push for forgetting only happens in learning situations. When the scientists blocked the main route into the hippocampus under other circumstances, the strength of its connections remained unaltered.

“One explanation for this is that there is limited space in the brain, so when you’re learning, you have to weaken some connections to make room for others,” says Gross. “To learn new things, you have to forget things you’ve learned before.”

The findings were made using genetically engineered mice, but with help from Maja Köhn’s lab at EMBL the scientists demonstrated that it is possible to produce a drug that activates this ‘forgetting’ route in the brain without the need for genetic engineering. This approach, they say, might be interesting to explore if one were looking for ways to help people forget traumatic experiences.

Funding: This work was supported by EMBL, EMBO, Pablo Olavide University, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Government of Andalusia, German Research Foundation, Chica and Heinz Schaller Research Foundation, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Source: Sonia Furtado Neves – EMBL

Image Source: The image is credited to John Wood/EMBL.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Rapid erasure of hippocampal memory following inhibition of dentate gyrus granule cells” by Noelia Madroñal, José M. Delgado-García, Azahara Fernández-Guizán, Jayanta Chatterjee, Maja Köhn, Camilla Mattucci, Apar Jain, Theodoros Tsetsenis, Anna Illarionova, Valery Grinevich, Cornelius T. Gross and Agnès Gruart in Nature Communications. Published online March 18 2016 doi:10.1038/ncomms10923

Abstract

Rapid erasure of hippocampal memory following inhibition of dentate gyrus granule cells

The hippocampus is critical for the acquisition and retrieval of episodic and contextual memories. Lesions of the dentate gyrus, a principal input of the hippocampus, block memory acquisition, but it remains unclear whether this region also plays a role in memory retrieval. Here we combine cell-type specific neural inhibition with electrophysiological measurements of learning-associated plasticity in behaving mice to demonstrate that dentate gyrus granule cells are not required for memory retrieval, but instead have an unexpected role in memory maintenance. Furthermore, we demonstrate the translational potential of our findings by showing that pharmacological activation of an endogenous inhibitory receptor expressed selectively in dentate gyrus granule cells can induce a rapid loss of hippocampal memory. These findings open a new avenue for the targeted erasure of episodic and contextual memories.

“Rapid erasure of hippocampal memory following inhibition of dentate gyrus granule cells” by Noelia Madroñal, José M. Delgado-García, Azahara Fernández-Guizán, Jayanta Chatterjee, Maja Köhn, Camilla Mattucci, Apar Jain, Theodoros Tsetsenis, Anna Illarionova, Valery Grinevich, Cornelius T. Gross and Agnès Gruart in Nature Communications. Published online March 18 2016 doi:10.1038/ncomms10923