Summary: Researchers have created a computational model that helps explain how mental images drawn from memory can be explained by the firing of specific neurons.

Source: UCL.

UCL researchers have developed a computational model showing how the mental images we have drawn from our memories can be explained by the firing of individual brain cells.

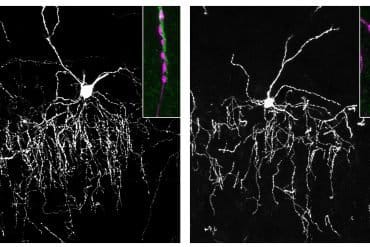

Their model, published in eLife and funded by Wellcome, the European Research Council and the Human Brain Project, shows how different neurons in the brain work together to store our experiences so that we can later conjure up a mental image and even imagine how a place would appear from a vantage point we haven’t experienced ourselves. The researchers pulled together evidence of which neurons signal our location and orientation as we move through space, such as place cells that respond differently depending on where we are in the world, and grid cells and head direction cells, while also proposing new types of neurons whose existence has yet to be confirmed, such as cells that signal the distances and directions to objects in our surroundings. An important aspect of the model is that when we perceive a scene, our sensory experience is encoded ‘egocentrically’ by neurons responding to objects according to their location ahead, left, or right of oneself. However, neurons in memory-related brain areas such as the hippocampus represent our location ‘allocentrically’ – relative to the scene around us.

The model explains how egocentric representations are transformed into allocentric representations for memory storage, and this transformation can also act in reverse, to allow memories to drive imagination of a scene corresponding to an egocentric point of view of the original event.

“Recalling life events can be thought of as ‘re-experiencing’ them in your imagination. Say you met someone at the train station – how can you later conjure up a mental image of that scene, remembering the person at a given distance and direction from you, against the backdrop of the train station? We built a computational model that shows how the neuronal activity across multiple brain regions underlying such an experience could be encoded and subsequently used to enable re-imagination of the event,” explained lead author Dr Andrej Bicanski (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience).

Professor Neil Burgess, the senior author, added, “Our model provides a mechanistic account of spatial memory and imagery, including cognitive concepts such as ‘episodic future thinking’ and ‘scene-construction.’ It also explains how different types of brain damage will differently affect these types of cognition, such as by producing different aspects of amnesia.”

The research team used their model to simulate a lesions of brain areas, e.g. confirming findings from studies in rats that show how damage to the hippocampus results in the inability to remember where objects were originally found relative to oneself and the environment. While they haven’t yet modelled a specific neurological disorder, they say the model could be a good starting point to investigate which forms of damage could result in which functional impairments in neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Funding: This study was supported by Wellcome.

Source: Barbara Benham – UCL

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Open access research for “A neural-level model of spatial memory and imagery” by Andrej Bicanski, and Neil Burgess in eLife. Published September 4 2018.

doi:10.7554/eLife.33752

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]UCL”How Brain Cells Work Together to Remember and Imagine Places.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 7 September 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/memory-imagination-places-9823/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]UCL(2018, September 7). How Brain Cells Work Together to Remember and Imagine Places. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved September 7, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/memory-imagination-places-9823/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]UCL”How Brain Cells Work Together to Remember and Imagine Places.” https://neurosciencenews.com/memory-imagination-places-9823/ (accessed September 7, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

A neural-level model of spatial memory and imagery

We present a model of how neural representations of egocentric spatial experiences in parietal cortex interface with viewpoint-independent representations in medial temporal areas, via retrosplenial cortex, to enable many key aspects of spatial cognition. This account shows how previously reported neural responses (place, head-direction and grid cells, allocentric boundary- and object-vector cells, gain-field neurons) can map onto higher cognitive function in a modular way, and predicts new cell types (egocentric and head-direction-modulated boundary- and object-vector cells). The model predicts how these neural populations should interact across multiple brain regions to support spatial memory, scene construction, novelty-detection, ‘trace cells’, and mental navigation. Simulated behavior and firing rate maps are compared to experimental data, for example showing how object-vector cells allow items to be remembered within a contextual representation based on environmental boundaries, and how grid cells could update the viewpoint in imagery during planning and short-cutting by driving sequential place cell activity.