How language gives your brain a break.

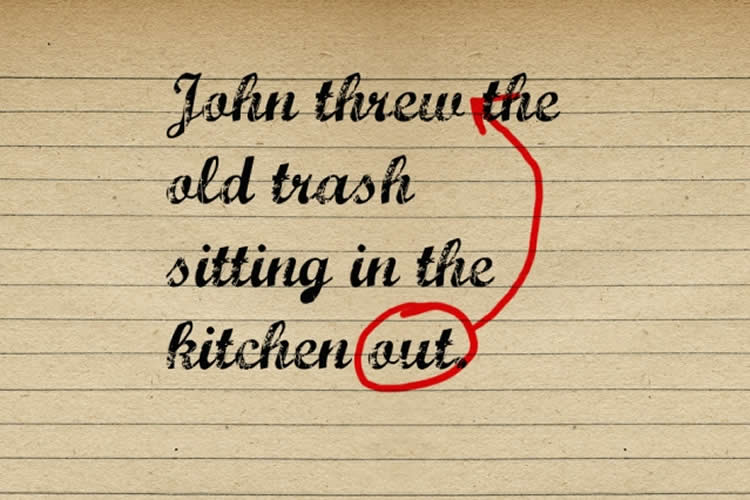

Here’s a quick task: Take a look at the sentences below and decide which is the most effective.

(1) “John threw out the old trash sitting in the kitchen.”

(2) “John threw the old trash sitting in the kitchen out.”

Either sentence is grammatically acceptable, but you probably found the first one to be more natural. Why? Perhaps because of the placement of the word “out,” which seems to fit better in the middle of this word sequence than the end.

In technical terms, the first sentence has a shorter “dependency length” — a shorter total distance, in words, between the crucial elements of a sentence. Now a new study of 37 languages by three MIT researchers has shown that most languages move toward “dependency length minimization” (DLM) in practice. That means language users have a global preference for more locally grouped dependent words, whenever possible.

“People want words that are related to each other in a sentence to be close together,” says Richard Futrell, a PhD student in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT, and a lead author of a new paper detailing the results. “There is this idea that the distance between grammatically related words in a sentence should be short, as a principle.”

The paper, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests people modify language in this way because it makes things simpler for our minds — as speakers, listeners, and readers.

“When I’m talking to you, and you’re trying to understand what I’m saying, you have to parse it, and figure out which words are related to each other,” Futrell observes. “If there is a large amount of time between one word and another related word, that means you have to hold one of those words in memory, and that can be hard to do.”

While the existence of DLM had previously been posited and identified in a couple of languages, this is the largest study of its kind to date.

“It was pretty interesting, because people had really only looked at it in one or two languages,” says Edward Gibson, a professor of cognitive science and co-author of the paper. “We though it was probably true [more widely], but that’s pretty important to show. … We’re not showing perfect optimization, but [DLM] is a factor that’s involved.”

From head to tail

To conduct the study, the researchers used four large databases of sentences that have been parsed grammatically: one from Charles University in Prague, one from Google, one from the Universal Dependencies Consortium (a new group of computational linguists), and a Chinese-language database from the Linguistic Dependencies Consortium at the University of Pennsylvania. The sentences are taken from published texts, and thus represent everyday language use.

To quantify the effect of placing related words closer to each other, the researchers compared the dependency lengths of the sentences to a couple of baselines for dependency length in each language. One baseline randomizes the distance between each “head” word in a sentence (such as “threw,” above) and the “dependent” words (such as “out”). However, since some languages, including English, have relatively strict word-order rules, the researchers also used a second baseline that accounted for the effects of those word-order relationships.

In both cases, Futrell, Gibson, and co-author Kyle Mahowald found, the DLM tendency exists, to varying degrees, among languages. Italian appears to be highly optimized for short sentences; German, which has some notoriously indirect sentence constructions, is far less optimized, according to the analysis.

And the researchers also discovered that “head-final” languages such as Japanese, Korean, and Turkish, where the head word comes last, show less length minimization than is typical. This could be because these languages have extensive case-markings, which denote the function of a word (whether a noun is the subject, the direct object, and so on). The case markings would thus compensate for the potential confusion of the larger dependency lengths.

“It’s possible, in languages where it’s really obvious from the case marking where the word fits into the sentence, that might mean it’s less important to keep the dependencies local,” Futrell says.

Other scholars who have done research on this topic say the study provides valuable new information.

“It’s interesting and exciting work,” says David Temperley, a professor at the University of Rochester, who along with his Rochester colleague Daniel Gildea has co-authored a study comparing dependency length in English and German. “We wondered how general this phenomenon would turn out to be.”

Futrell, Gibson, and Mahowald readily note that the study leaves larger questions open: Does the DLM tendency occur primarily to help the production of language, its reception, a more strictly cognitive function, or all of the above?

“It could be for the speaker, the listener, or both,” Gibson says. “It’s very difficult to separate those.”

Source: Peter Dizikes – MIT

Image Credit: The image is credited to Christine Daniloff/MIT

Original Research: Abstract for “Large-scale evidence of dependency length minimization in 37 languages” by Richard Futrell, Kyle Mahowald, and Edward Gibson in PNAS. Published online August 3 2015 doi:10.1073/pnas.1502134112

Abstract

Large-scale evidence of dependency length minimization in 37 languages

Explaining the variation between human languages and the constraints on that variation is a core goal of linguistics. In the last 20 y, it has been claimed that many striking universals of cross-linguistic variation follow from a hypothetical principle that dependency length—the distance between syntactically related words in a sentence—is minimized. Various models of human sentence production and comprehension predict that long dependencies are difficult or inefficient to process; minimizing dependency length thus enables effective communication without incurring processing difficulty. However, despite widespread application of this idea in theoretical, empirical, and practical work, there is not yet large-scale evidence that dependency length is actually minimized in real utterances across many languages; previous work has focused either on a small number of languages or on limited kinds of data about each language. Here, using parsed corpora of 37 diverse languages, we show that overall dependency lengths for all languages are shorter than conservative random baselines. The results strongly suggest that dependency length minimization is a universal quantitative property of human languages and support explanations of linguistic variation in terms of general properties of human information processing.

“Large-scale evidence of dependency length minimization in 37 languages” by Richard Futrell, Kyle Mahowald, and Edward Gibson in PNAS. Published online August 3 2015 doi:10.1073/pnas.1502134112