A new study contends different areas of brain responsible for external versus internal threats.

When doctors at the University of Iowa prepared a patient to inhale a panic-inducing dose of carbon dioxide, she was fearless. But within seconds of breathing in the mixture, she cried for help, overwhelmed by the sensation that she was suffocating.

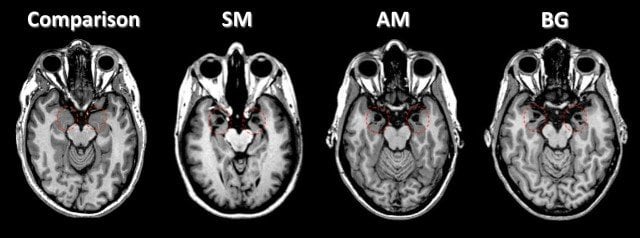

The patient, a woman in her 40s known as SM, has an extremely rare condition called Urbach-Wiethe disease that has caused extensive damage to the amygdala, an almond-shaped area in the brain long known for its role in fear. She had not felt terror since getting the disease when she was an adolescent.

In a paper published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, the UI team provides proof that the amygdala is not the only gatekeeper of fear in the human mind. Other regions, such as the brainstem, diencephalon, or insular cortex, could sense the body’s most primal inner signals of danger when basic survival is threatened.

“This research says panic, or intense fear, is induced somewhere outside of the amygdala,” says John Wemmie, associate professor of psychiatry at the UI and senior author on the paper. “This could be a fundamental part of explaining why people have panic attacks.”

If true, the newly discovered pathways could become targets for treating panic attacks, post-traumatic stress syndrome, and other anxiety-related conditions caused by a swirl of internal emotional triggers.

“Our findings can shed light on how a normal response can lead to a disorder, and also on potential treatment mechanisms,” says Daniel Tranel, professor of neurology and psychology at the UI and a corresponding author on the paper.

Decades of research have shown the amygdala plays a central role in generating fear in response to external threats. Indeed, UI researchers have worked for years with SM, and noted her absence of fear when she was confronted with snakes, spiders, horror movies, haunted houses, and other external threats, including an incident where she was held up at knife point. But her response to internal threats had never been explored.

The UI team decided to test SM and two other amygdala-damaged patients with a well-known internally generated threat. In this case, they asked the participants, all females, to inhale a gas mixture containing 35 percent carbon dioxide, one of the most commonly used experiments in the laboratory for inducing a brief bout of panic that lasts for about 30 seconds to a minute. The patients took one deep breath of the gas, and quickly had the classic panic-stricken response expected from those without brain damage: They gasped for air, their heart rate shot up, they became distressed, and they tried to rip off their inhalation masks. Afterward, they recounted sensations that to them were completely novel, describing them as “panic.”

“They were scared for their lives,” says first author Justin Feinstein, a clinical neuropsychologist who earned his doctorate at the UI last year.

Wemmie had looked at how mice responded to fear, publishing a paper in the journal Cell in 2009 showing that the amygdala can directly detect carbon dioxide to produce fear. He expected to find the same pattern with humans.

“We were completely surprised when the patients had a panic attack,” says Wemmie, also a faculty member in the Iowa Neuroscience Graduate Program.

By contrast, only three of 12 healthy participants panicked—a rate similar to adults with no history of panic attacks. Notably, none of the three patients with amygdala damage has a history of panic attacks. The higher rate of carbon dioxide-induced panic in the patients suggests that an intact amygdala may normally inhibit panic.

Interestingly, the amygdala-damaged patients had no fear leading up to the test, unlike the healthy participants, many who began sweating and whose heart rates rose just before inhaling the carbon dioxide. That, of course, was consistent with the notion that the amygdala detects danger in the external environment and physiologically prepares the organism to confront the threat.

“Information from the outside world gets filtered through the amygdala in order to generate fear,” Feinstein says. “On the other hand, signs of danger arising from inside the body can provoke a very primal form of fear, even in the absence of a functioning amygdala.”

Notes about this neurology research article

Contributing authors include Colin Buzza, Robin Follmer, and William Coryell, from the UI Department of Psychiatry; Rene Hurlemann, from the University of Bonn Department of Psychiatry; Nader Dahdaleh, of the UI Department of Neurosurgery; and Michael Welsh, UI professor of internal medicine and molecular physiology and biophysics and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. Buzza and Hurlemann are co-first authors on the paper.

Contacts: John Riehl and Richard Lewis – University of Iowa

Source: University of Iowa press release

Image Source: The image is adapted from the University of Iowa press release and is credited to the Iowa Neurological Patient Registry at the University of Iowa.

Original Research: Abstract for “Fear and panic in humans with bilateral amygdala damage” by Justin S Feinstein, Colin Buzza, Rene Hurlemann, Robin L Follmer, Nader S Dahdaleh, William H Coryell, Michael J Welsh, Daniel Tranel and John A Wemmie in Nature Neuroscience. Published online February 3 2013 doi:10.1038/nn.3323

Full open access research for “The Amygdala Is a Chemosensor that Detects Carbon Dioxide and Acidosis to Elicit Fear Behavior” by Adam E. Ziemann, Jason E. Allen, Nader S. Dahdaleh, Iuliia I. Drebot, Matthew W. Coryell, Amanda M. Wunsch, Cynthia M. Lynch, Frank M. Faraci, Matthew A. Howard III, Michael J. Welsh and John A. Wemmie in Cell. Published online November 25 2009 DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.029