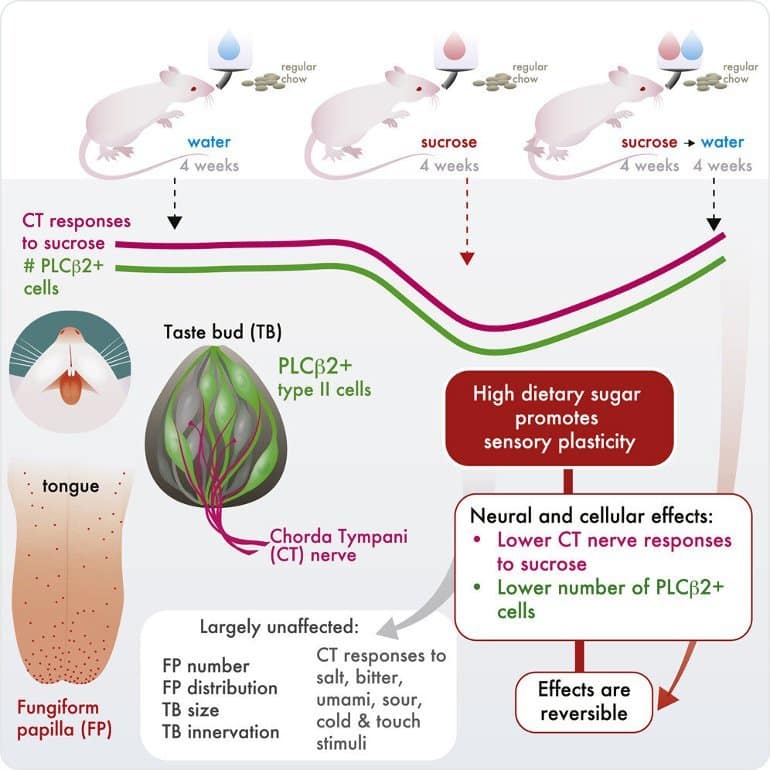

Summary: In rats, high-sugar diets lower the ability of the taste system to sense sweetness. However, curbing high sugar in the diet allowed sensitivity to sweetness to return.

Source: University of Michigan

For many people, a high-sugar diet has become almost accidental.

Three-quarters of food in the supermarket has added sugar, according to University of Michigan researcher Monica Dus, leading the scientist to wonder whether our sense of taste can become dulled to sweetness. Now, in a study of rats, a collaboration of U-M researchers discovered that, yes, a diet of high sugar does lower the ability of the taste system to sense sweetness.

Dus wanted to further examine whether this phenomenon was a physiological effect taking place in rats’ senses consuming the high-sugar diet. The group, a collaboration that included U-M scientists Robert Bradley, Charlotte Mistretta and Carrie Ferrario, found that the responsiveness of the nerve that transmits sweetness information from the tongue to the brain was reduced by almost 50% in rats fed a high-sugar diet.

Their results are published in the journal Current Biology.

“A number of years ago, a study showed that decreasing the levels of sugar in the diet of humans led to people perceiving sugar as more intense. But how is that happening?” said Dus, associate professor of molecular, cellular and developmental biology.

“Several of our previous papers found that sugar dulls sweet taste in fruit flies by lowering the responsiveness of the nerve and reprogramming the taste cells, but flies are still just flies. I really wanted to understand if and how it was happening in mammals.”

Dus reached out to U-M School of Dentistry professors Bradley and Mistretta, who have studied how taste functions and how it is changed by diet and disease. The team also connected with Ferrario, associate professor of pharmacology at the U-M Medical School, who studies the neurobiology of ingestive behavior in rats.

The researchers gave one group of rats their typical diet and access to sugar water. A control group of rats received their regular diet and access to plain water. After four weeks, the researchers used electrodes to record the responses of the nerve as the tongue was stimulated with different solutions. This nerve carries taste information from the front of the rat’s tongue, which contains the taste buds cells that sense chemicals, to the brain.

Then, the researchers gave the rats sweet, bitter, sour, salty and umami-flavored solutions, and measured the rats’ responses to touch and cold. While they did this, they tested the response of the front of the tongue to those flavors and sensations.

The researchers found no difference in the rats’ reaction to salty, bitter, sour and umami flavors, nor to touch or cold, but they saw a 50% reduction in the nerve’s responsiveness to the sweet sucrose (table sugar) solution.

“This is not a subtle effect,” Dus said. “It is really strong, and it only took four weeks.”

At the end of the four weeks, the researchers also found that the rats had not gained weight from sugar. The scientists then put the rats back on their normal diet with plain water. After another four weeks, they retested the rats’ sensitivity to sweetness, and found that it had been restored.

“That’s potentially good news for us,” Dus said. “If you eat a lot of sugar, but decide to cut out sugar, this shows you can recover your taste (assuming the system works the same).”

This result was somewhat expected, Dus said. Previously, Mistretta and Bradley found that the taste system is very plastic and can recover from drug treatments that disrupt it, such as chemotherapy.

The group then delved into why this might be happening. Looking at the rats’ tongues, they did not find a change in the rats’ taste papillae, the structures that house the taste buds in the tongue. This makes sense, Dus said: if they had, they likely would have also found changes to the rats’ sensitivity to other tastes.

The researchers also found no changes to the number of taste buds on the tongue, nor in how the nerve connected to the taste buds. But, looking inside the taste buds, they found fewer cells that detected sweetness in the rats given a high-sugar diet.

In future studies, Dus and Ferrario will examine how these taste changes affect eating and the activity of cells that receive sweetness information deep in the brain. For example, Dus previously found that in flies, lower sweet sensation dampens the release of dopamine, decreasing satiety and triggering overeating. Is this also occurring in the rat?

There is much evidence that sugar and fat diets affect dopamine and the food learning systems in the brains of humans and mammals, but the causes of these alterations remain largely unknown. Do they originate from the changes in our senses, specifically the taste changes observed here?

“Because we are mammals and our taste systems are similar to rats, this is the best available evidence that a high-sugar diet is changing the sensory system,” Dus said.

“So this might affect your food choices. This might affect your metabolism. But also, the other important implication is that if your taste system is truly plastic, it’s likely that if we reformulate foods to contain less sugar, our taste buds are going to learn to eat and like the food as much as we enjoyed that extra sugary stuff today.”

The group wrote a collaborative internal grant proposing to study how sugar changes sweetness in rats, which funded their work. The work began in 2018, first with undergraduate student Hannan Driks and then with MCDB postdoctoral researcher Hayeon Sung and dental school postdoctoral researcher Iva Vesela. The COVID shutdown and subsequent research restrictions halted the project for nearly 1.5 years.

About this diet and sensory neuroscience research news

Author: Press Office

Source: University of Michigan

Contact: Press Office – University of Michigan

Image: The image is credited to the researchers

Original Research: Closed access.

“High-sucrose diet exposure is associated with selective and reversible alterations in the rat peripheral taste system” by Hayeon Sung et al. Current Biology

Abstract

High-sucrose diet exposure is associated with selective and reversible alterations in the rat peripheral taste system

Highlights

- Sucrose consumption showed specific and selective effects on the peripheral taste system

- Dietary sugar lowered chorda tympany responses to sucrose and the number of PLCβ2+ cells

- Responses to other sensory qualities and modalities were largely unaffected

- We observed that phenotypes were restored after sucrose was removed from the diet

Summary

Elevated sugar consumption is associated with an increased risk for metabolic diseases. Whereas evidence from humans, rodents, and insects suggests that dietary sucrose modifies sweet taste sensation, understanding of peripheral nerve or taste bud alterations is sparse.

To address this, male rats were given access to 30% liquid sucrose for 4 weeks (sucrose rats). Neurophysiological responses of the chorda tympani (CT) nerve to lingual stimulation with sugars, other taste qualities, touch, and cold were then compared with controls (access to water only). Morphological and immunohistochemical analyses of fungiform papillae and taste buds were also conducted.

Sucrose rats had substantially decreased CT responses to 0.15–2.0 M sucrose compared with controls. In contrast, effects were not observed for glucose, fructose, maltose, Na saccharin, NaCl, organic acid, or umami, touch, or cold stimuli. Whereas taste bud number, size, and innervation volume were unaffected, the number of PLCβ2+ taste bud cells in the fungiform papilla was reduced in sucrose rats. Notably, the replacement of sucrose with water resulted in a complete recovery of all phenotypes over 4 weeks.

The work reveals the selective and modality-specific effects of sucrose consumption on peripheral taste nerve responses and taste bud cells, with implications for nutrition and metabolic disease risk.