Summary: A specific gene inherited from Neanderthals may be responsible for the shape of our noses.

The study suggests that the shape of our noses may have evolved through natural selection in response to the different climates and environments that our ancestors faced as they migrated around the world.

The research highlights the importance of understanding the genetic diversity of different populations to better understand the evolution of human traits.

Key Facts:

- The researchers used data from over 6,000 volunteers across Latin America, of mixed European, Native American and African ancestry, to study the genetic influence on facial features.

- They identified 33 genome regions associated with face shape, 26 of which they were able to replicate in comparisons with data from other ethnicities using participants in east Asia, Europe, or Africa.

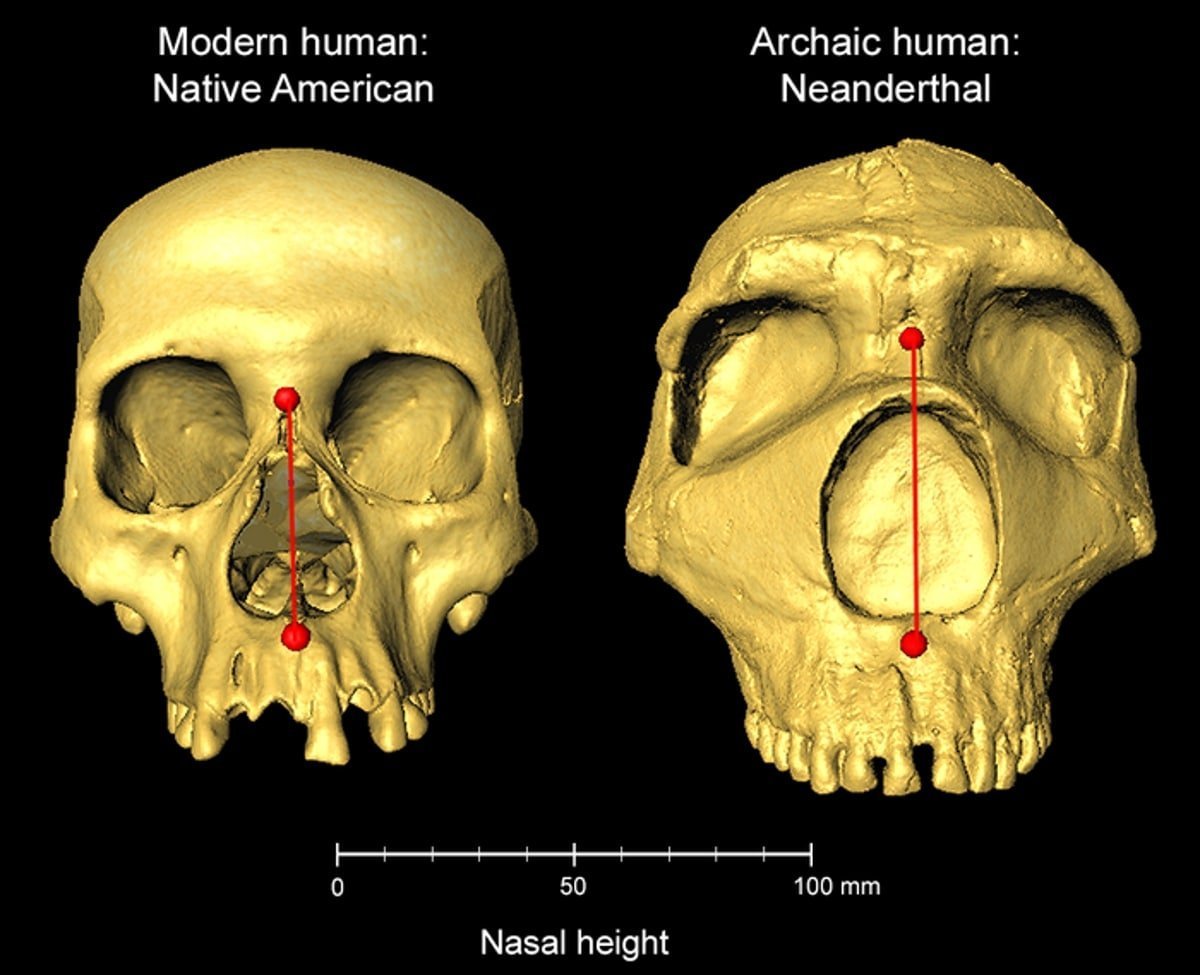

- In one particular genome region called ATF3, many people in the study with Native American ancestry had genetic material in this gene that was inherited from the Neanderthals, contributing to increased nasal height. This gene region has signs of natural selection, suggesting that it conferred an advantage for those carrying the genetic material.

Source: UCL

Humans inherited genetic material from Neanderthals that affects the shape of our noses, finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

The new Communications Biology study finds that a particular gene, which leads to a taller nose (from top to bottom), may have been the product of natural selection as ancient humans adapted to colder climates after leaving Africa.

Co-corresponding author Dr Kaustubh Adhikari (UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment and The Open University) said: “In the last 15 years, since the Neanderthal genome has been sequenced, we have been able to learn that our own ancestors apparently interbred with Neanderthals, leaving us with little bits of their DNA.

“Here, we find that some DNA inherited from Neanderthals influences the shape of our faces. This could have been helpful to our ancestors, as it has been passed down for thousands of generations.”

The study used data from more than 6,000 volunteers across Latin America, of mixed European, Native American and African ancestry, who are part of the UCL-led CANDELA study, which recruited from Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico and Peru.

The researchers compared genetic information from the participants to photographs of their faces – specifically looking at distances between points on their faces, such as the tip of the nose or the edge of the lips – to see how different facial traits were associated with the presence of different genetic markers.

The researchers newly identified 33 genome regions associated with face shape, 26 of which they were able to replicate in comparisons with data from other ethnicities using participants in east Asia, Europe, or Africa.

In one genome region in particular, called ATF3, the researchers found that many people in their study with Native American ancestry (as well as others with east Asian ancestry from another cohort) had genetic material in this gene that was inherited from the Neanderthals, contributing to increased nasal height.

They also found that this gene region has signs of natural selection, suggesting that it conferred an advantage for those carrying the genetic material.

First author Dr Qing Li (Fudan University) said: “It has long been speculated that the shape of our noses is determined by natural selection; as our noses can help us to regulate the temperature and humidity of the air we breathe in, different shaped noses may be better suited to different climates that our ancestors lived in.

“The gene we have identified here may have been inherited from Neanderthals to help humans adapt to colder climates as our ancestors moved out of Africa.”

Co-corresponding author Professor Andres Ruiz-Linares (Fudan University, UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment, and Aix-Marseille University) added: “Most genetic studies of human diversity have investigated the genes of Europeans; our study’s diverse sample of Latin American participants broadens the reach of genetic study findings, helping us to better understand the genetics of all humans.”

The finding is the second discovery of DNA from archaic humans, distinct from Homo sapiens, affecting our face shape. The same team discovered in a 2021 paper that a gene influencing lip shape was inherited from the ancient Denisovans.*

The study involved researchers based in the UK, China, France, Argentina, Chile, Peru, Colombia, Mexico, Germany, and Brazil.

About this genetics research news

Author: Chris Lane

Source: UCL

Contact: Chris Lane – UCL

Image: The image is credited to Dr Kaustubh Adhikari, UCL

Original Research: Open access.

“Automatic landmarking identifies new loci associated with face morphology and implicates Neanderthal introgression in human nasal shape” by Kaustubh Adhikari et al. Communication Biology

Abstract

Automatic landmarking identifies new loci associated with face morphology and implicates Neanderthal introgression in human nasal shape

We report a genome-wide association study of facial features in >6000 Latin Americans based on automatic landmarking of 2D portraits and testing for association with inter-landmark distances. We detected significant associations (P-value <5 × 10−8) at 42 genome regions, nine of which have been previously reported.

In follow-up analyses, 26 of the 33 novel regions replicate in East Asians, Europeans, or Africans, and one mouse homologous region influences craniofacial morphology in mice.

The novel region in 1q32.3 shows introgression from Neanderthals and we find that the introgressed tract increases nasal height (consistent with the differentiation between Neanderthals and modern humans).

Novel regions include candidate genes and genome regulatory elements previously implicated in craniofacial development, and show preferential transcription in cranial neural crest cells.

The automated approach used here should simplify the collection of large study samples from across the world, facilitating a cosmopolitan characterization of the genetics of facial features.