Summary: Epigenetic memory of environmental changes can be passed on for at least 14 generations in C. elegans, a new study finds.

Source: CRG.

Scientists at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona and the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute and The Institute for Health Science Research Germans Trias i Pujol (IGTP) in Badalona, Spain, have discovered that the impact of environmental change can be passed on in the genes of tiny nematode worms for at least 14 generations – the most that has ever been seen in animals. The findings will be published on Friday 21st April in the journal Science.

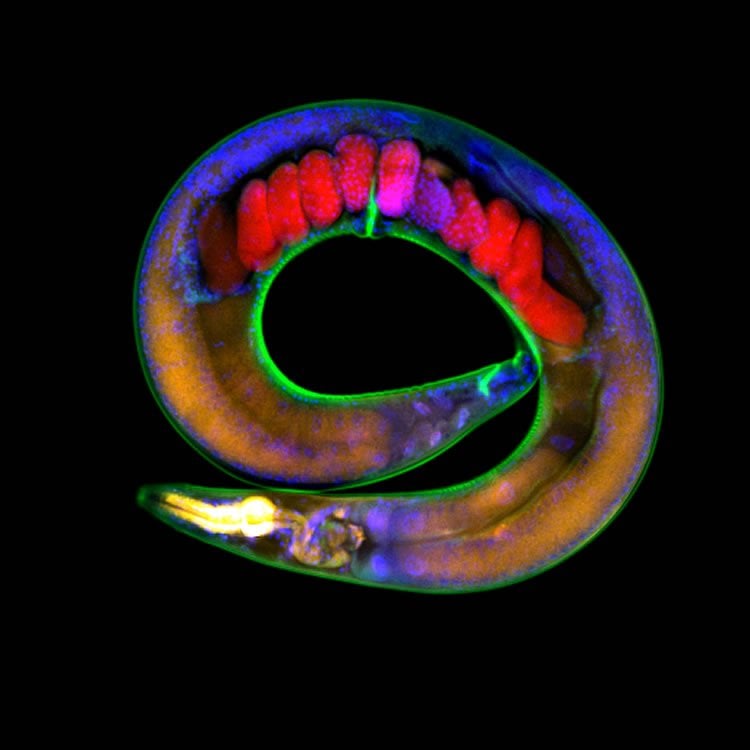

Led by Dr Ben Lehner, group leader at the EMBL-CRG Systems Biology Unit, ICREA and AXA Professor, together with Dr Tanya Vavouri CRG Alumna and currently group leader at the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute and the Institute for Health Science Research Germans Trias i Pujol (IGTP), the researchers noticed that the impact of environmental change can be passed on in the genes for many generations while studying C. elegans worms carrying a transgene array – a long string of repeated copies of a gene for a fluorescent protein that had been added into the worm genome using genetic engineering techniques.

If the worms were kept at 20 degrees Celsius, the array of transgenes was less active, creating only a small amount of fluorescent protein. But shifting the animals to a warmer climate of 25 degrees significantly increased the activity of the transgenes, making the animals glow brightly under ultraviolet light when viewed down a microscope.

When these worms were moved back to the cooler temperature, their transgenes were still highly active, suggesting they were somehow retaining the ‘memory’ of their exposure to warmth. Intriguingly, this high activity level was passed on to their offspring and onwards for 7 subsequent generations kept solely at 20 degrees, even though the original animals only experienced the higher temperature for a brief time. Keeping worms at 25 degrees for five generations led to the increased transgene activity being maintained for at least 14 generations once the animals were returned to cooler conditions.

Although this phenomenon has been seen in a range of animal species – including fruit flies, worms and mammals including humans – it tends to fade after a few generations. These findings, which will be published on Friday 21st April in the journal Science, represent the longest maintenance of transgenerational environmental ‘memory’ ever observed in animals to date.

“We discovered this phenomenon by chance, but it shows that it’s certainly possible to transmit information about the environment down the generations,” says Lehner . “We don’t know exactly why this happens, but it might be a form of biological forward-planning,” adds first author of the study and CRG alumnus Adam Klosin. “Worms are very short-lived, so perhaps they are transmitting memories of past conditions to help their descendants predict what their environment might be like in the future,” adds CRG Alumna and co-leader of this study Tanya Vavouri.

Comparing the transgenes that were less active with those that had become activated by the higher temperature, Lehner and his team discovered crucial differences in a type of molecular ‘tag’ attached to the proteins packaging up the genes, known as histone methylation.

Transgenes in animals that had only ever been kept at 20 degrees had high levels of histone methylation, which is associated with silenced genes, while those that had been moved to 25 degrees had largely lost the methylation tags. Importantly, they still maintained this reduced histone methylation when moved back to the cooler temperature, suggesting that it is playing an important role in locking the memory into the transgenes.

The researchers also found that repetitive parts of the normal worm genome that look similar to transgene arrays also behave in the same way, suggesting that this is a widespread memory mechanism and not just restricted to artificially engineered genes.

Funding: This work was supported by a European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator grant (616434), the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (BFU2011-26206 and SEV-2012-0208), the AXA Research Fund, the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation, Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR), Framework Programme 7 project 4DCellFate (277899), and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory–Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG) Systems Biology Program. Adam Klosin was partially supported by a la Caixa Fellowship. Eduard Casas and Tanya Vavouri were supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (BFU2015-70581) and by an FI AGAUR Ph.D. fellowship to Eduard Casas.

Source: CRG

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is adapted from the CRG news release.

Original Research: Abstract for “Transgenerational transmission of environmental information in C. elegans” by Adam Klosin, Eduard Casas, Cristina Hidalgo-Carcedo, Tanya Vavouri, and Ben Lehner in Science. Published online April 21 2017 doi:10.1126/science.aah6412

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]CRG “Discovering the Basics of ‘Active Touch'” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 21 April 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/genetics-environmental-memory-6476/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]CRG (2017, April 21). Discovering the Basics of ‘Active Touch’. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved April 21, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/genetics-environmental-memory-6476/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]CRG “Discovering the Basics of ‘Active Touch’.” https://neurosciencenews.com/genetics-environmental-memory-6476/ (accessed April 21, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Transgenerational transmission of environmental information in C. elegans

The environment experienced by an animal can sometimes influence gene expression for one or a few subsequent generations. Here, we report the observation that a temperature-induced change in expression from a Caenorhabditis elegans heterochromatic gene array can endure for at least 14 generations. Inheritance is primarily in cis with the locus, occurs through both oocytes and sperm, and is associated with altered trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) before the onset of zygotic transcription. Expression profiling reveals that temperature-induced expression from endogenous repressed repeats can also be inherited for multiple generations. Long-lasting epigenetic memory of environmental change is therefore possible in this animal.

“Transgenerational transmission of environmental information in C. elegans” by Adam Klosin, Eduard Casas, Cristina Hidalgo-Carcedo, Tanya Vavouri, and Ben Lehner in Science. Published online April 21 2017 doi:10.1126/science.aah6412